How Athletes From Tropical Countries Train For The Winter Olympics

Bobsled. Cross-country skiing. Figure skating. Alpine skiing. These are but four of the 15 sports played in the Winter Olympics. Every four years, athletes from around the globe gather to compete in cold climate sports. Naturally, growing up in a cold environment is going to give you an edge. According to Statista, Norway has won a total of 368 medals of which 132 were gold since the Winter Games began in 1924. In fact, the Norwegian cross-country skier Marit Bjoergen won 15 medals alone between 2002 and 2018. Certainly, growing up in a region where the culture practices winter sports has its advantages.

This has not stopped tropical countries from trying to break the ice ceiling. Since 1972, athletes representing tropical countries have regularly participated in the Winter Games. However, not a one has won a medal. But they have earned a different kind of Olympian glory. They are fan-favorite Olympic underdogs which is reflected in the 1993 film "Cool Runnings," about the 1988 Jamaican bobsled team. People cheer for these athletes as unlikely heroes, perhaps pondering how they were drawn to winter sports and how on earth could they train where there is no snow. Let's take a look at some of these tropical countries and the athletes who are the Winter Games perennial underdogs.

The Philippines

According to the Olympics' official website, the first warm weather country to participate in the Winter Olympics was a Mexican bobsleigh team in 1928. However, Mexico is considered a "warm weather" country and not truly tropical. The very first fully tropical country to participate in the games was therefore the Philippines in 1972 when that country sent Juan Cipriano and Ben Nanasca to Sapporo, Japan, as Alpine skiers. According to the East and Bays Courier, the pair were cousins who were adopted by New Zealanders as teenagers.

They ended up in Andorra where they took up skiing in the Pyrenees, learning to ski in a traditional way. Nanasca and Cipriano skied in France, Spain, and Switzerland before the Swiss government paid for their training under a government program. "The Training of Olympic Alpine Ski Racers" relates how this is seasonal with conditioning occurring in the off-season followed by practical training and competition from October to March. Still, even in off-seasons, some alpine skiers will go to glaciers just for additional training. The key is that for a citizen from a tropical country to become an Olympic-level alpine skier, they must travel. Through their training, both men were able to represent the Philippines in the games. Nanasca finished 42nd in the Giant Slalom, and Cipriano did not finish. As for Nanasca, being a teenager at the time of his Olympic appearance burned him out from skiing. However, his Olympian status helped him immigrate permanently to New Zealand.

Jamaica

Of all tropical countries to participate in the Winter Olympics there is none more famous than Jamaica. This was brought about by their 1988 bobsled team whose story was very loosely told in the 1993 film, "Cool Runnings." While the film, according to Olympics.com, took certain liberties, it nevertheless captured the underdog spirit of the team. ESPN related the true story of how an attache for the American embassy in Jamaica, George Fitch, after seeing a push cart derby in the island country's mountains, realized that Jamaica could produce a great bobsled team.

In Fitch's reckoning, you did not need so much ice skills as you needed sprinting speed and pushing power. Fitch spent $92,000 personally to finance the team. Today reported that the team trained at the Jamaica Defense Force Base, Lake Placid, and Austria with used equipment and ad hoc facilities such as a concrete track. Their appearance in Calgary showed dogged determination as the inexperienced team crashed and pushed their sled over the finish line. But their Olympic spirit has won them more than a medal.

As for the film, Fitch commented to ESPN, "I was personally offended by the film because I'm not a disgraced Olympic bobsledder who's a drunk, who's spending the rest of my life in some pool hall. But that's Hollywood."

Tonga

The island nation of Tonga only has ice available from freezers. Yet this nation of about 170 islands (as detailed by Britannica) also sought Olympic glory and — maybe a bit of beefcake — through the ambitions of Taekwondo athlete Pita Taufatofua. The Guardian reported that Taufatofua first came into the world's eye in 2016 at the Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro. There, he ignored Olympic officials who ordered him to wear a suit as he stripped off his clothes, lathered himself with coconut oil and wore a traditional Tongan ta'ovala while shirtless. While he received no medals, he definitely received fame.

He then swore he'd compete at the 2018 games in PyeongChang, South Korea, as a cross country skier being inspired by "Cool Runnings." Taufatofua, unlike other athletes who compete for tropical countries, had never left his home to train. He said to the Guardian "I chose it because it made no sense." He trained himself by watching races on YouTube and then practicing in the park using roller skis. He then amassed $40,000 in credit card debt travelling to cold weather countries to compete. He managed to qualify at a race in Iceland. Thrilled at being in the Olympics again, he went shirtless for the opening ceremony, risking hypothermia. The Olympian had no intention of medaling — just competing and avoiding trees. He managed to come in 110th place, but in reality became a star of the show. He now is a shirtless, serial Olympian.

Ghana

The Ghanese skier Kwame Nkrumah-Acheampong has one of the coolest nicknames in Olympic history: "The Snow Leopard." According to Mentalfloss, Nkrumah-Acheampong was first introduced to skiing after he left Ghana and moved to the United Kingdom in 2000. He became a receptionist at an indoor ski center and became hooked on the sport. He commented to the Daily Record, "All I had ever known about skiing was watching a James Bond film, so it really just took off from there." To make a point of his difference from other skiers, he wore a leopard print snowsuit.

Training wise, the Snow Leopard said to the Daily Record, "The coaches said I had natural talent and I've never found skiing difficult. But it has been a hard fight. Even now, when I go to big events, there are people who just refuse to believe that an African can ski." Still, his skill grew to the point where he became the first Olympian to represent Ghana at the Winter Games in 2010. His chief ambition was to finish. This he did, finishing 53rd out of 54 – the rest of the 102 athletes did not complete the course. After the Olympics, the Snow Leopard worked to train Ghana's own batch of young skiers, this time using grass skis which use wheels to simulate the feel of the powder.

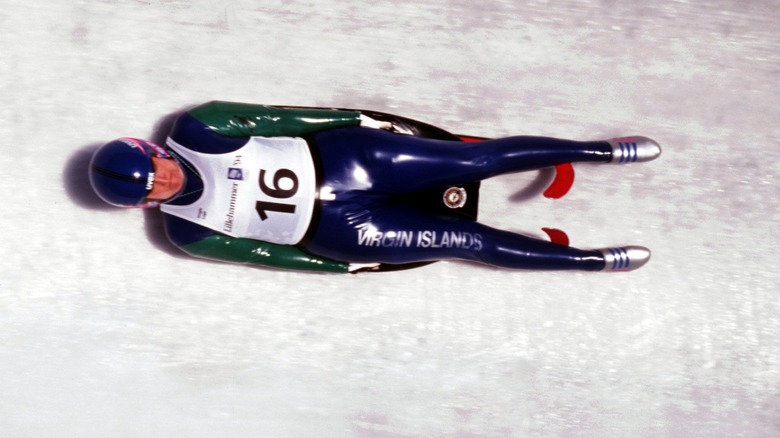

U.S. Virgin Islands

Anne Abernathy is not only notable for being a Olympian luge athlete from a tropical country, but she is also, according to CNN, the oldest female athlete to have competed in the sport. As a result, she has been called "Grandma Luge." The Baltimore Sun reported that Abernathy was first drawn to the luge in 1983 at age 30 after witnessing the sport at Lake Placid, New York's Olympic course.

Luge training can be done in all seasons. As HowStuffWorks describes, during the summer months and certainly in warmer climes, swimming, lifting weights, and anything to develop the upper body is critical. Practice runs occur in the winter months in facilities that Abernathy would necessarily have to travel to. Yet determination brought Abernathy not just to the 1988 Calgary Games, but, as Olympics.com reports, her luging in every Winter Games since until 2002. What is more, Abernathy qualified for the 2006 games when she was well into her 50s. However, she had to bow out due to a training accident.

Still, she made her point. Abernathy stated to the Los Angeles Times, "Because I come from a country with no training facilities and started at an age when most lugers are retiring, my goal is to do the best I can possibly do, look professional on the sled and put 100% into it." In that way, Grandma Luge shows as much Olympic spirit as any gold medalist.

Malaysia

Malaysia made its debut in the Winter Olympics in 2018 with figure skater Julian Yee. According to KXAN, as a young boy, Yee was drawn to figure skating because it was indoors and air-conditioned, a relief from the tropical climate of Malaysia. His biggest challenge was finding places to train. Ice rinks are limited in Malaysia, and most are small venues at malls. In fact, he needed to convince rink owners to open early to allow him to train.

However, it was apparent he needed to step up his game. At age 12, he was sent to a figure skating camp in South Korea. Yee stated, "It was my first proper training camp, my first time without my parents, my first time training with other people, my first time training with people from other countries." However, to train for international competition, he needed to move to Canada which was helped through crowdfunding. In 2018, he ranked 25th in men's singles, according to Olympics.com.

Singapore

Singapore made its winter Olympics debut in 2018 when speed skater Cheyenne Goh arrived in PyeongChang. According to CNN, Goh's family had emigrated from Singapore to Canada when she was 4, and she very quickly became immersed in cold weather athletic culture. According to Today she started off with ice hockey, but after witnessing the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics on television, she knew she wanted to be a speed skater. Her training began, and she even took a gap year from high school to give the ice her full attention.

Mothership explains that since she was a Singaporean national, it would be easier for her to qualify for the Olympics than with the Canadian team. As a result, she started competing under Singapore's flag in 2016. Goh, however, was not just an absentee athlete. She journeyed to Singapore for training, according to Olympics, in the only one Olympic-sized skating rink in the country. Then, before the games, she spent a month in South Korea training with the national speed skating coach Chun Lee-kyung in order to acclimate herself to the open air environment where she would compete. While she trained hard and showed the Olympic spirit, she could not medal and took 28th place in the short track event. Still, Goh was still honored by being the sole delegate from Singapore and was honored to carry the national flag of her birth country.

Senegal

In 1984, Lamine Guèye of Senegal became the first Black African to compete in the Winter Games. Gueye, according to Reuters, was a member of the country's elite and the grandson of a prominent Senegalese politician who served on the French parliament when the country was a colony. He and his sister moved to France at a young age, and it was while he was at a boarding school in Switzerland that he fell in love with skiing. Much of Guèye's training was with other skiers within Europe. However, his training also was blemished by racism. Reuters quoted him in an interview: "I found myself confronted with prejudices — that Africans, blacks, had not skied, until now,"

Despite these obstacles, he managed to qualify himself as an Olympian from Senegal after he registered the Senegalese Ski Federation (he neglected to tell officials he was the only member). 1984 was not the only appearance of Guèye. Olympics.com tells us that he competed in the 1992 and 1994 Games, also in Alpine skiing. Since then, he has become an outspoken critic of the structure of the Olympics claiming that modern qualification standards squeeze out many less well-funded countries.

Nigeria

Located on the West African coast, Nigeria has (according to Britannica) a climate ranging from tropical to arid. The country also has a strong tradition of athletics, and it is from this that Nigeria drew its first Winter Olympians. CNN reported that in 2018, Seun Adigun, Ngozi Onwumere, and Akuoma Omeoga represented the country at its first Winter Games. The three were all track and field athletes with Adigun even competing in the 100-meter hurdles at the 2012 London Summer Games.

Much of their training involved travel, but when in Nigeria, they used a homemade wooden sled called the "Mayflower." CNN quoted Adigun, who was the sled driver, as saying, "I built [it] when I was a brakeman in the US. So, when I decided to start the Nigerian team it just became the bobsled 101 tool. We spend a lot of time doing reps on the Mayflower, on turf or track surfaces."

These three were joined by Simidele Adeagbo who was the first African and Black female skeleton Olympian. According to WCNC, for her there is little training she could in Nigeria but had to globetrot to get to the facilities to train her in the skeleton, which is a headfirst ice race. While none of these athletes have medaled, they have nevertheless been trailblazers in their sport and for their country.

Brazil

While attending college in the United States in the late 1990s, Eric Maleson was, as reported by the Seattle Times, perhaps inspired by "Cool Runnings." He longed to start a bobsled team for his own native Brazil. To that end, he recruited Edson Bindilatti and Ricardo Raschini. The Washington Post reported that the team primarily trained in Lake Placid, New York, where Bindilatti was shocked at their initial 90 mile per hour run.

The team became known as the "Frozen Bananas." They competed in the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah, where they came in 27th as detailed by Olympics.com. Talk ensued to devise a pushcart track for a sled with wheels so that they could train in Brazil. This was the beginning of a bobsled tradition in the country, and Bindilatti became the team captain. However, most of the team's training still occurs in Lake Placid in partnership with their American counterparts.

The Brazilians are proud of their achievement. The Washington Post quoted Bindilatti stating, "We are no longer the ugly ducklings. We want to introduce bobsled to Brazil and show the world that a winter sport can be practiced in a tropical country."

Haiti

Haiti seems an unlikely country to send athletes to the Winter Olympicas. Not only is it in the heart of the tropical Caribbean, but as pointed out by Britannica, it has suffered such chronic misfortunes that it seems that training for the Olympics, much less the Winter Games, would be a luxury. But the story of Richardson Viano is remarkable. Viano was, as reported by Olympics.com, an orphan from Port-Au-Prince who was adopted in 2005 by an Italian family who lived near Briançon, France. His adopted father started training him to ski.

While Viano's exact training regimen is unknown, it can safely be assumed that he followed the practices outlined in "The Training of Olympic Alpine Skiers" which breaks up the year into periods of physical conditioning and then periods of competition. Practical training would include arriving early on hardpacked snow to practice speed runs. Nothing like this could be done in Haiti, so Viano has the benefit which many tropical Olympians who compete in winter sports have — they live abroad in countries with snow and slopes. This is how that Viano became an elite skier.

During the 2018 games he did not qualify for the French team. He soon got in touch with the Haitian Ski Federation which recruited him to compete on behalf of Haiti. He obtained a Haitian passport the next year. He then managed to qualify to become the sole member of Haiti's inaugural debut in the Winter Games in 2022 in Beijing.

Fiji

Fiji is an island archipelago in the South Pacific with an average winter low temperature (as reported by Britannica) in the 60s. The country is about as far from snow as possible. Still, in 1988, Rusiate Rogoyawa became the first Fijian to compete in the Winter Olympics as a cross-country skier. According to "Backpacker," Rogoyawa had been in Norway as a student and was immediately drawn to Nordic skiing. In 1986, he returned and stayed to learn the sport.

Rogoyawa's greatest challenge was adapting to the Norwegian culture which was not as laid back as Fiji's, sometimes forgetting to show up for training. Still he was a "good skier and true amateur." It seems that Rogoyawa wasn't the most punctual of athletes, but he certainly must have trained well enough to reach the Olympics. According to "The Evolution of Cross-Country Skier Training," by the mid-1980s, cross-country skiers often ran through mountainous regions and weight trained in order to prepare their bodies for the rigors of skiing, as well as follow goal-oriented training for distance and speed.

"XXIII Olympiad" reports that while Rogoyawa finished 83rd out of 85, he showed the Olympic spirit when he stated, "I think we should be given a chance to try our best. I can never become as good as the talents in Norway, but I can show that I can ski." According to Olympics.com, he competed again at Lillehammer in 1994, taking 88th place in the 10 kilometer cross-country event.