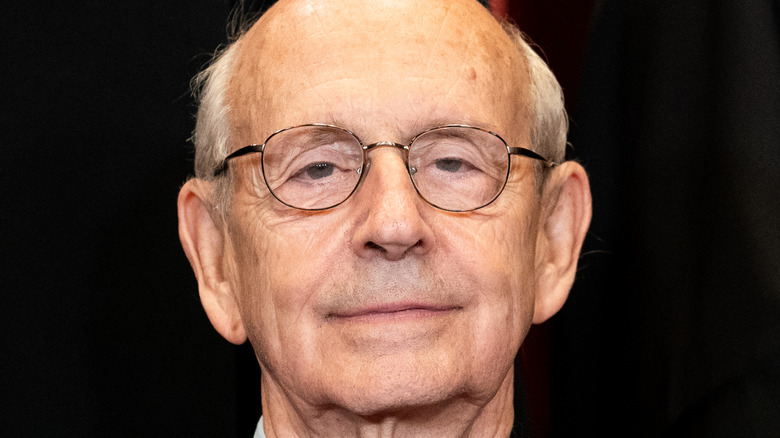

5 Facts About Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer

In January 2022, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer announced that he would retire within the year (via CNN). The 83-year-old judge was first appointed to the Supreme Court in 1994, so all the trials and scandals of the past 27 years, from the death penalty to Obamacare, have appeared in his docket. Breyer is a stalwart liberal, like his colleagues Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The final years of his career have seen holding up the court's liberal minority against conservative champions like Trump appointees Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh. Nevertheless, his judgeship has always had a mild, cautious character, and insisted on the fundamental difference between the judicial branch and the politicized executive and legislative branches.

"It is wrong to think of the court as another political institution," he said in 2021. "If the public sees judges as 'politicians in robes,' its confidence in the courts, and in the rule of law itself, can only diminish, diminishing the court's power" (per CNN).

He's a longstanding liberal

Stephen Breyer's liberal views have never been a secret. Born in San Francisco, a famously left-leaning city, Breyer's mother was an activist for the League of Women Voters, which may have shaped his later views on abortion and other matters. A series of prominent Democratic Party leaders would help pave the way to his eventual seat on the nation's most powerful court. As a Harvard Law student, Breyer worked for Senator Ted Kennedy, who mentored the promising young lawyer. According to CNN, Jimmy Carter appointed Breyer to the Court of Appeals in 1980, and Bill Clinton brought him before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1994 as a Supreme Court nominee, shortly after Harry Blackmun's retirement.

Breyer is pro-choice, dissenting vigorously to the Court's decision to uphold Texas' ban on abortions after six weeks, and casting a skeptical eye on attempts to loosen gun control. However, as Vox notes, he broke ranks with fellow Democrats to support deregulating the airline industry. Breyer has insisted that there are no liberal or conservative courts, and that a judge's personal opinions have less to do with their decision than most people think.

He's mild-mannered and professorial

Stephen Breyer isn't a personality the way his late friends Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia were. He never had a pop culture cult, and he never bellowed at anyone or smoked a pipe in his Senate hearing, as Scalia famously did (via C-SPAN). Nor was he as stony silent as the longest-serving current member of the Supreme Court, Clarence Thomas.

Breyer is a gentle, mild presence. His questions have tended to devolve into long, professorial monologues, posing complicated hypotheticals to the lawyers arguing before him. In 2020, he implied to Slate that his low profile was strategic, a trick he learned from his old mentor, Ted Kennedy. "If you have a choice between achieving 20 or 30% of what you'd like or being the hero of all your friends, choose the first," he said. "When you disagree with someone, get them to talk about the problem. Eventually — it happens almost always — they'll say something you agree with. Then you can say, 'Let's work with that.'"

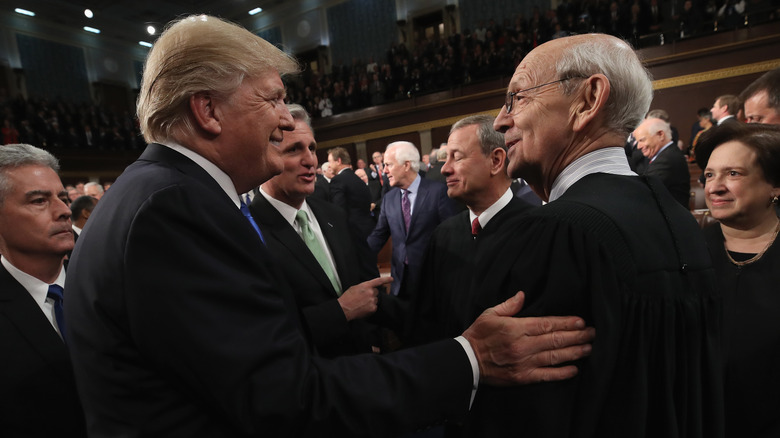

He opposed court packing

The issue of "court packing" cropped up in American media in 2020, shortly after the Senate confirmed President Trump's nominee to the Supreme Court, Amy Coney Barrett. According to Rutgers University professor David Noll, court packing technically refers to changing the number of justices who sit on the bench, generally expanding the number. More to the point, it's a way of manipulating the court for partisan ends. Democrats in 2020 were livid that Republicans had stonewalled President Obama's Supreme Court nominees, refusing to give them the time of day, only to use their Congressional majority to rush conservatives into seats as soon as they opened. Could adding more justices give Democrats a chance at balancing the Supreme Court?

Breyer was against the idea. He believed that the inevitable race to keep growing the court as Congressional majorities shifted would "erode trust" (via ABC News), and called for Democrats to "think long and hard before embodying those changes in law."

A strong admirer of France

It is a little-known fact that Justice Breyer is a Francophile, an admirer of French culture. He particularly enjoys French literature, once giving a lecture on Camus' novel and political allegory, "The Plague" (via SCOTUSBlog). In 2013, he was inducted into the French Academy, a major cultural institution in France that only allows 12 non-French members at any given time. The New York Times noted that Breyer replaced Crown Prince Otto von Habsburg, patriarch of the storied Austrian dynasty, who had died in 2011, which gives a good of idea of the academy's prestige.

Of course, Breyer is not the only recent justice with wide-ranging cultural interests. His colleagues, the good friends Scalia and Ginsburg, were such opera fanatics that the Washington National Opera gave them roles as extras in Strauss' "Ariadne auf Naxos" (per Forward). But none have had Breyer's special connection to France.

His wife is an aristocrat

Stephen Breyer married Dr. Joanna Hare in 1967. Hare, according to The Washington Post, was the daughter of the Viscount Blakenham. Her mother was related to the Duke of Marlborough and the Spencer-Churchill family, a clan that has included Winston Churchill, Lady Diana, and Boris Johnson. The family's motto, inscribed on their coat of arms, is "Ogi profanum" — "I hate what is profane" — and British prime ministers and senior Conservative Party members sometimes came for dinner. Hare attended Oxford but went to Harvard for her doctorate, where she met the future Supreme Court justice.

The match seemed awkward at first, not only because Breyer was an American, but because he was solidly middle-class. But Hare seems to have found that refreshing, a pleasant exit from the stiff world of clubs, titles, and traditions. After her doctorate, she became a senior psychologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. The couple have three children and six grandchildren.