The Most Notable Deaths To Happen In Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is almost 1,000 years old, built by William the Conqueror shortly after he successfully invaded England in 1066. It's been a royal residence ever since, with thousands of people living under its (very extensive) roof over the centuries. Of course, when you have that many people living there, you're going to have a significant number who also die there.

While no doubt many servants and minor officials breathed their last at Windsor, many of their names are lost to history. But plenty of royal and political headliners died at the castle as well, and their stories are recorded in much greater detail.

It just goes to show you can't take it with you: Dying in a castle might sound pretty swish, but at the end of the day, you are still dead. Whether young or old, expiring peacefully or in great agony, these are the most notable deaths at Windsor Castle.

Philippa of Hainault

Philippa of Hainaut was born sometime around 1314, according to Britannica, in modern-day France. Her father ruled an area now part of Belgium and the Netherlands, but she would only spend her childhood there. In 1327, when she was barely a teenager, Philippa was married off to King Edward III of England. If there was any silver lining to getting married to someone she didn't choose and burdened by the responsibilities of a queen while still so young, it was that at least the relationship was age-appropriate, with Edward only one or two years older. The couple would travel together around the British Isles and Western Europe and had 12 children.

While most foreign queens ended up being intensely disliked, Philippa managed to win the English over. History Extra calls her "one of England's best-loved queens." The chronicler Thomas Walsingham wrote she was "the most noble woman." The French author Jean Froissart recorded that she was "the most courteous, noble, and liberal queen that ever reigned." And even the chancellor of England complimented Philippa, saying, "No Christian king or other lord in the world ever had so noble and gracious a lady for his wife as our lord the king has had."

Philippa seems to have kept her husband in check, because after she died at Windsor Castle in 1369, eight years before Edward passed away, his mistress took over and things started to fall apart after what was otherwise a long and peaceful reign.

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Queen Elizabeth II has been on the throne longer than any other British monarch, and by her side every step of the way was her devoted husband Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

According to the New York Times, Prince Philip was born into the Greek royal family. However, he grew up in England and spoke English as his first language. After leaving school, he joined the British Navy and served in World War II. He met the then-Princess Elizabeth when she was about 13, and for her at least, it was love at first sight. The couple married in 1947, when she was 21 and he was 26. They would go on to have four children.

While Prince Philip had health problems that sent him to the hospital repeatedly in his last years, it seemed like he might live forever. Even after he retired from public duties in 2017, he was seen at royal functions like Prince Harry and Meghan Markle's wedding. Prince Philip died on April 9, 2021, at Windsor Castle with the queen by his side. The BBC reported he was the "longest-serving royal consort in British history." The royal correspondent Nicholas Witchell said Prince Philip was "utterly loyal in his belief in the importance of the role that the Queen was fulfilling – and in his duty to support her ... It was the importance of the solidity of that relationship, of their marriage, that was so crucial to the success of her reign."

Albert, Prince Consort

Queen Victoria is often remembered as an elderly lady in all black, but this was only true for the second half of her life. For two decades, from 1840 to 1861, she had a passionate marriage to her cousin Prince Albert. It was his death at a relatively young age that plunged her into permanent mourning for the next 40 years.

Albert was born to a minor German royal family in Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in 1819, according to Britannica. Albert's father and Queen Victoria's mother were siblings, making the future couple first cousins. Their marriage was essentially arranged by their uncle, but fortunately, the pair fell in love. They married in 1840 and went on to have nine children. While Victoria might have loved him, everyone else in England seemed to hate Albert. Despite this, he worked hard for his wife and his adopted country.

PBS records that only weeks before he died, Albert told Victoria, "I do not cling to life. You do; but I set no store by it. If I knew that those I love were well cared for, I should be quite ready to die tomorrow ... I am sure if I had a severe illness, I should give up at once. I should not struggle for life. I have no tenacity for life." At that point, he was healthy, but soon he was struck down with what was once assumed to be typhoid fever, although now historians are less sure what the deadly disease was. He died at Windsor Castle, aged 41.

George III

King George III is probably most famous for being on the throne when England lost their colonies in the Revolutionary War, but he's also famous for going mad. The first signs he was losing his mind didn't appear until well after America's independence, but whatever you might have been taught about the guy in school, you can still feel bad for the mental torture he went through for decades.

According to History, George III took the throne in 1760, when he was 20 years old. Only five years later, he suffered "a short nervous breakdown." He would then remain mentally sound even through losing the American colonies, until 1788, when he became mentally unbalanced for months. But the state of his mind improved again. Once 1810 rolled around, though, all hope was lost, and it was accepted the king was, as his biography on the official website of the British royal family puts it, "permanently deranged." His son George, the Prince of Wales, took over as regent for his father for the next decade. It's unknown what caused the king's mental illness. The popular diagnosis for years was porphyria, although historians no longer believe that was the case.

The year before George III died, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (husband of "Frankenstein" author Mary Shelley) wrote the poem "England in 1819," which opened with the line "An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King." George spent his last years isolated at Windsor Castle and died there in 1820.

Katherine of England

While child mortality rates in the past were sky-high, that didn't make the tragedy of losing a child any less painful. Sadly, this was something that King Henry III and Queen Eleanor of Provence would have to suffer due to the early death of their youngest child.

Born in 1253, Katherine of England was Henry's fifth child and third daughter. (Her grandfather was King John of Robin Hood fame.) It was soon evident that the poor girl was unwell. Since it's almost impossible to diagnose someone from 800 years ago, it's not clear what was wrong with her, but various sources (including Berkshire History) say she was unable to hear or speak, and may have had a degenerative disorder. She was sent to be raised by a surrogate family at Windsor, but her father and mother still spent time with her there. She also had a pet goat and made friends with the local children. Katherine died in Windsor Castle aged just 3 and a half.

According to A. Armstrong's Ph.D. thesis "The Daughters of Henry III," the loss of their toddler daughter "caused her parents inconsolable grief." They buried her in the most illustrious location for English royals to be laid to rest, Westminster Abbey. The Abbey's official site says her tomb was ornamented by "two images in gilt bronze and silver (one was probably of St. Catherine) and a silver plated wooden effigy." It was also covered in 180 precious stones, per "The Two Eleanors of Henry III."

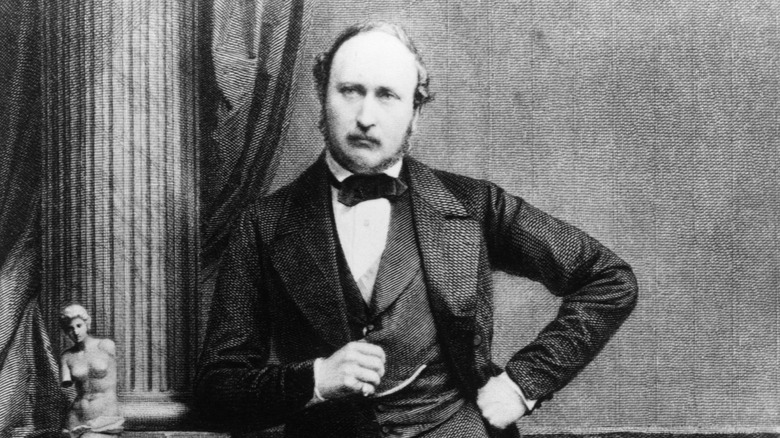

Sir John Sparrow David Thompson

The royal family has strict protocols for almost every situation, but there's very few things you could do in their home that would be less appropriate than just up and dying. Especially if you were only in their castle in the first place to receive an honor. Sadly, no one seemed to have told the Canadian prime minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson that it would be a real faux pas to die during his visit to Windsor Castle in 1894.

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, Sir John was a lawyer and politician whose career peaked in 1892 when he became the third prime minister of Canada. While it was now its own country, Queen Victoria was still the head of state, so Sir John was invited to London to become a member of the Imperial Privy Council.

The Dictionary of Canadian Biography says that by this point, Sir John was unwell: massively overweight and under a great deal of stress. Doctors he consulted in London weren't worried though, so the prime minister went for a short vacation to Europe, then returned to England to be sworn in on the Privy Council. He attended the ceremony at Windsor Castle and stayed for lunch afterwards. But once he sat down, Sir John passed out. When he came to, he said, "It seems too absurd to faint like this." Shortly after, he fell into the arms of the man sitting next to him, dead of a heart attack at 49 years old.

Prince William, Duke of Gloucester

Queen Anne, played to Oscar-winning perfection by Olivia Colman in the 2018 film "The Favourite," was pregnant basically all the time. But of her 18 pregnancies, 17 of them ended in miscarriage, stillbirth, or a child that died before they were even a year old. The boy who lived, as it were, was Prince William, Duke of Gloucester. Born in 1689, he was the precious heir on which all hopes rested, according to Historical Portraits.

But Prince William was not a well child. Victorian Era says he suffered from seizures shortly after his birth, and didn't speak until he was three. He could not walk until he was 5 years old and may have had other developmental difficulties. He was often sick, sometimes needing to be spoon-fed by servants, even as he reached adolescence. The best modern guess is that he suffered from hydrocephalus.

But it was not any of these issues that killed him. Instead, it was a dreaded disease that was finally eradicated in the 20th century thanks to a vaccine: smallpox. On his 11th birthday, the prince started to feel unwell, which was rationalized as overexertion from his party. But then he developed telltale signs of the disease, dying at Windsor Castle in 1700. The death of the one and only direct heir to the throne was a serious problem for the monarch, on par with the issues faced by Henry VIII when he had no male heirs.

George IV

George IV is less well-known to many people than his father George III, but he's just as interesting a character. Historic UK says his personal life was seriously messy, spending money like water and having affairs and illegitimate children all over the place, before finally submitting to an arranged marriage (so Parliament would pay off his debts) that was one of mutual hatred. He became king in 1820.

When George IV fell ill in 1830, his every breath was suddenly news. The medical journal The Lancet (via the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine) reported on his changing condition over several weeks, including "attacks of embarrassment in his breathing" or the fact he managed to get "several hours of refreshing sleep." Morbidly obese and dosing himself with huge amounts of opioids, it was clear to observers the king was in trouble. One duchess said his body was so swollen it looked "enormous, like a feather bed."

His doctors didn't hide the fact he was dying from the king. A few months after George died, Sir Henry Halford gave a speech to the Royal College of Physicians and explained how this approach was beneficial: "The King, upon [learning] the danger of the disorder, immediately prepared himself for death. Having set his house in order he received the sacrament and, from the administration of that holy office, declared that he had received the greatest comfort and consolation. By pursuing this course His Majesty's cheerfulness was preserved, and he died without being disturbed by the prospect of approaching dissolution."

Sir John Barton

Sir John Barton was an engineer whose curiosity was seemingly never-ending. Born in 1771, Sir John had an illustrious career. He invented dozens of things during his life, including "a floating compass, a hydrostatic balance, a hydro static floating lamp, a draw-bench for use at the Mint, and an 'atometer' with which a millionth of an inch was rendered a sensible measure to the eye," Nature reports. As comptroller of the Royal Mint, he was especially concerned with making it harder to forge banknotes.

Sir John was friendly with King William IV and Queen Adelaide, visiting them often at Windsor Castle, according to the Science Museum Group. It was there that he died in 1834, aged 63.

A letter written from Windsor (via Grace's Guide to British Industrial History) tried to sum up the talents of this prolific inventor: "Well versed in astronomy, in metallurgy, in experimental and natural philosophy, he was often consulted by ingenious artists who sought to apply scientific principles to practical uses, and those studies which would have been labor to a frivolous mind were the delight and recreation of Sir John Barton. Frequently after a day of intense application to business has he devoted the night to the contemplation of heavenly bodies." But the writer also makes sure to record that Sir John wasn't just smart, but a super great guy as well. After his death, King William had a plaque in his friend's honor mounted in Windsor's St. George's Chapel.

William IV

Even fans of British royal history could be forgiven for forgetting that William IV existed. (Incidentally, he was the last king named William, so the current Duke of Cambridge will one day be William V.) William IV was born in 1765, and reigned from 1830-37, in between his brother George IV and his niece Queen Victoria.

Not only was his reign short, but as a person he didn't have too much crazy stuff going on that would get him pages in the history books. According to his biography on the official British royal family site, William spent his teenage years and early 20s in the Navy. He returned to dry land in 1790 and settled down with an actress named Dorothea Bland (a.k.a. Mrs. Jordan), whom he spent the next 20 years with. Westminster Abbey's official site records they had 10 children together. However, William had to actually marry someone more respectable, and eventually he left Bland for Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. As king he was hands off, saying, "I have my view of things, and I tell them to my ministers. If they do not adopt them, I cannot help it. I have done my duty."

William managed to hold on to this life until his niece Victoria turned 18. Had he died before that important date, a regent could have been appointed, most likely her mother and the hated Sir John Conroy. William IV died on June 20, 1837 at Windsor Castle, and was buried in the royal chapel there.

John Brown

Queen Victoria was very much in love with her husband Prince Albert, and never stopped mourning him after he died. But as a lonely widow, even the dour queen needed some attention from the opposite sex. She found it in her late husband's "Highland servant" John Brown.

The Scotsman brought the queen out of deep mourning and accompanied her on horseback rides. They shared a very strong friendship, so strong some historians think it can't have been platonic. But Queen Victoria was going to outlive yet another man she loved very much. John Brown died suddenly at Windsor Castle in 1883. Their extremely close relationship was so well known that Brown's obituary appeared in the New York Times.

A letter that was only discovered at the beginning of this century (via the Guardian) showed how his death deeply affected the queen. She wrote about the "present, unbounded grief for the loss of the best, most devoted of servants and truest and dearest of friends." Her very real pain at losing Brown is evident even through the formal writing: "Perhaps never in history was there so strong and true an attachment, so warm and loving a friendship between the sovereign and servant ... life for the second time is become most trying and sad to bear ... the blow has fallen too heavily not to be very heavily felt." When Queen Victoria died in 1901, her will instructed she be buried with various mementos of her late husband Prince Albert, as well as those of John Brown.

Prince Alfred of Great Britain

Smallpox inoculation in the late 1700s was not the same as the successful vaccine that eventually wiped out the disease in the 20th century. There was a minor but very real chance that instead of getting protection from smallpox in the future, the patient would get sick and die due to the inoculation itself. But because of how dangerous and contagious smallpox was, by the late 1700s, most people who had access to inoculation for themselves and their children decided it was worth the risk. George Washington even mandated the Continental Army be inoculated in 1777, the National Parks Service reports.

According to "Kings of Georgian Britain," only five years later, the youngest children of King George III and Queen Charlotte were inoculated, and the procedure was successful for all of them except the 1-year-old Alfred. He became unwell, and not even a trip to the fresh air of the coast was enough to ward off the symptoms of smallpox. Alfred was then brought to Windsor Castle, where he died: "Yesterday morning died at the Royal Palace, Windsor, his Royal Highness Prince Alfred, their Majesties youngest son. The Queen is much affected at this domestic calamity, probably more so on account of its being the only one she has experience after a marriage of 20 years and having been the mother of 14 children."

The whole royal family was distraught, and while court etiquette didn't require an official period of mourning for a toddler, Alfred was still buried with great ceremony in Westminster Abbey.

Queen Elizabeth II's last Corgi

Queen Elizabeth II is known for her love of dogs, specifically the Pembroke Welsh Corgi. The adorable dogs with the short stubby legs can be seen in hundreds of pictures with the queen over the years, dating back to when she received her first one from her father George VI in 1944. (The then-Princess Elizabeth and her younger sister Princess Margaret accidentally "invented" a new breed called the Dorgi, when Margaret's Dachshund had puppies with Elizabeth's Corgi.) They even starred with the queen in a scene with James Bond during the 2012 London Olympics Opening Ceremony.

Perhaps the only bad thing about dogs is that their owners usually outlive them. The queen has outlived many, many of her dogs. The American Kennel Club estimates she's had more than 30 over the years. And since the queen spends a lot of time at Windsor Castle, many of her dogs have died there.

In 2018, People reported that the queen's final full-bred Corgi died at Windsor. Whisper was 12 years old and according to one royal commenter, the queen was "very attached to the dog. Whisper was a friendly chap." This left Queen Elizabeth with two Dorgis, Vulcan and Candy. Sadly, two years later, Vulcan would also die at Windsor. An anonymous source from the palace told the tabloid The Sun (via CNN), "clearly the loss of a loved pet is upsetting." Queen Elizabeth has said she will not get any more dogs, since she doesn't want to leave them behind when she dies.

Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother

For decades, two Queen Elizabeths lived together in the various royal palaces in Britain. One was Queen Elizabeth II, and the other was her mum. Known after her husband George VI's death in 1952 as the Queen Mother (let's stick with her title to avoid confusion here), the other Queen Elizabeth had a long, exciting life.

The daughter of a minor Scottish aristocrat, she married into the royal family when her husband was just the Duke of York, and not expected to ever be king, Biography records. But when his father George V died in 1936, and his brother Edward VIII abdicated that same year, suddenly George VI found himself on the throne. His wife became queen consort, and would help support the country through WWII. The Queen Mother continued her royal work once her daughter took the throne.

Despite suffering repeated health issues, the Queen Mother just kept on going, living to be 101. On March 20, 2002, Queen Elizabeth II released a statement saying "Her beloved mother, Queen Elizabeth, died peacefully in her sleep this afternoon, at Royal Lodge, Windsor." A palace spokesperson (via the Guardian) went into more detail: "Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother had become increasingly frail in recent weeks following her bad cough and chest infection over Christmas. Her condition deteriorated this morning and her doctors were called. Queen Elizabeth died peacefully in her sleep at 3:15 this afternoon at Royal Lodge. The Queen was at her mother's bedside."

Victoria, Duchess of Kent

Queen Victoria had a complicated relationship with her mother, Victoria, Duchess of Kent. The queen was an only child, and her father had died when she was less than a year old, according to Royal Central. Her mother never remarried, and kept the future queen in relative seclusion at Kensington Palace.

Once Queen Victoria took the throne at 18, relations between the pair thawed a bit. And while the world would not see how thoroughly the queen could be consumed by grief at the loss of a loved one until the death of her husband Prince Albert in December 1861, Queen Victoria got in some good practice when she lost her mother almost exactly nine months prior.

Royal Central says the 74-year-old duchess went downhill quickly, writing notes telling her ladies-in-waiting, "..these pains torment me very much." It was clear she was dying. Her death came not in the castle itself, but in Frogmore House on the Windsor estate. Queen Victoria recorded in her diary, "I kissed her dear hand and placed it next my cheek; but, though she opened her eyes, she did not, I think, know me. She brushed my hand off ... I went out to sob ... I asked the doctors if there was no hope. They said, they feared, none whatever." When the end came, the queen wrote, "It was quite painless ... I held her dear, dear hand in mine to the very last, which I am truly thankful for! But the watching that precious life going out was fearful!"