The Chinese Pantheon Of Gods Explained

China today recognizes five major religions, which include Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism. The Law Library of Congress explains that China also recognizes "many folk beliefs." These are the inheritance of traditional Chinese polytheistic religion, which the World History Encyclopedia states has existed for at least seven millennia and far outages all the major world religions of today.

This pantheon developed out of the worship of personifications of nature or various concepts that resulted in a huge pantheon of over 200 distinct deities. These are still influential in Chinese spirituality today; for example, Taoists and Buddhists aside from the main dictates of their religion can venerate the gods of this complex pantheon. Still, it is also important to realize that at any given time in China's long history, divine pantheons were often composed of different sets of gods. Here are some of the most prominent members of that pantheon who have long been venerated as living divinities throughout China's history.

Shangdi: the Lord on High

In the traditional Chinese pantheon, there is no greater god than Shangdi. Britannica translates the god's name as "Lord on High," who was sometimes just called "Di." However, World History Encyclopedia explains that Shangdi was also called the Jade Emperor or the Yellow Emperor. Shangdi controlled the weather, provided victory in battle, and determined how rich was the yearly harvest. He was also responsible for law and justice.

The god was worshiped first during the Shang Dynasty (1046-226 B.C.E.), where he was considered to be a semi-legendary divine king. As time passed he became supplanted by the concept of a god called Tian, which is by some considered interchangeable with Shangdi. "Understanding Di and Tian," by Ruth H. Chang, provides more details on Shangdi murky nature, including that Shangdi may even refer to a group of gods. What is clear is that there was no cultic worship of the god as there was of, say, the Greek god Zeus or the Norse god Odin. This may very well be because people were more concerned about practical matters and tended to worship their local deities more rather than a distant celestial supreme god.

Xi Wangmu: The Queen Mother of the West

In Chinese folklore, the queen goddess Xi Wangmu (sometimes Xiwangmu or Xing-Wang-Mu) lived in the land of Xihua ("West Flower") in the Kunlun Mountains. According to the World History Encyclopedia, this goddess of immortality ruled over mainly female divinities and spirits.

Britannica explains that her palace contained a garden where the peach of immortality grew. This fruit ripened every 3,000 years upon which there was a general celebration. The goddess sometimes presented these fruits to chosen mortals, such as emperors of the Zhou and Han dynasties.

Curiously, the goddess, also known as the Queen Mother of the West, was originally not so refined. As described in the "Handbook of Chinese Mythology," Xi Wangmu was originally a feral goddess of disaster, sickness, and punishment. However, she evolved to become the highest goddess of the Chinese pantheon. In these last iterations, she became the consort of Shangdi. In any event, as early as the Han Dynasty she was one of the most worshiped deities because it was thought that by venerating her, one could achieve longevity. This is seen today in the yearly Peach Saucer Festival held on the goddess' birthday at the Wangmu Pool.

Yinglong: the Dragon King

Chinese iconography is filled with images of dragons, and there is no greater dragon in China's pantheon than the winged Yinglong, the Dragon King. As the "Handbook of Chinese Mythology" explains, Yinglong, which literally means "Responding Dragon," is called such because he came to the aid of the mythical emperor Huangdi against his enemy Chiyou by causing floods. After the battle, Yinglong was said to have settled in South China, which explains why rain is more abundant there. Yinglong became known, therefore, as a god of rain, both of storm and also gentle showers.

World History Encyclopedia also tells us that Yinglong held domain over the sea under the name Hong Shen. As a result, people venerated the Dragon King on land for agriculture, but also offshore for smooth sailing. Yinglong also could assume human form, usually as an old man with the sun behind his head. It is notable that Yinglong wasn't the only dragon in Chinese mythology. According to "Sacred and Mythological Animals," by Yowann Byghan, dragons were elemental in nature so there were also dragons for earth, the heavens, thunder, and other functions.

Nuwa and Fuxi: The Parents of Humanity

In Chinese mythology humans were created by the mother goddess Nuwa. This particular goddess, as told by "The Handy Mythology Answer Book," by David A. Leeming, was depicted as having a body of a serpent with a human head. The myth, as summarized in "Myths and Legends of the World," explains that the goddess was lonely. Therefore, she formed humans from the mud of the Yellow River. A less subscribed to variation of the myth, as summarized by "World History," explains that she created humans by sleeping with her brother, Fuxi. Nuwa was also said to have killed beasts and put the sky above to form a world in which humans could thrive. As for Fuxi, he is credited to giving humans fire, metallurgy, animal husbandry, and teaching them how to fish.

For these reasons both Nuwa and Fuxi are considered the progenitors of the human race, as well as their teachers. There is still a cult surrounding Fuxi as he is yet worshiped at the Renzu Temple in Huaiyang, which was his mythical birthplace.

Sun Wukong: The Monkey God

In the Chinese pantheon, Sun Wukong, the Monkey God or Monkey King, appears later in China's history. As the name implies, this god was a monkey and a mischief maker. An article in the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies explains that the god originated during the Tang Dynasty in the fourth century C.E. but does not first appear in texts until the time of the Southern Song, centuries later. In the 16th century, the Monkey King becomes a main character in Wu Chengen's famous novel, "Journey to the West," which probably cemented Sun Wukong's prominent status.

As for such a strange god's origins, "The Mythology Book" describes how Sun Wukong was born from a union of heaven and earth and grew so ambitious that he became a demon. He was able to transform into dozens of other animals, jump halfway across the world, and wielded a staff that obeyed his commands. At his death, he was forced to the underworld where he surreptitiously erased his name from the book of life and death. Thus, he became immortal. However, he grew very troublesome, even eating the peaches that granted immortality and defeating any foes sent to kill him. At last the Buddha intervened by trapping the Monkey King into his hand and transforming the god into a mountain so that he was trapped. His escape centuries later occurs in "Journey to the West," where he becomes a Buddha himself.

Lei Gong: The God of Thunder

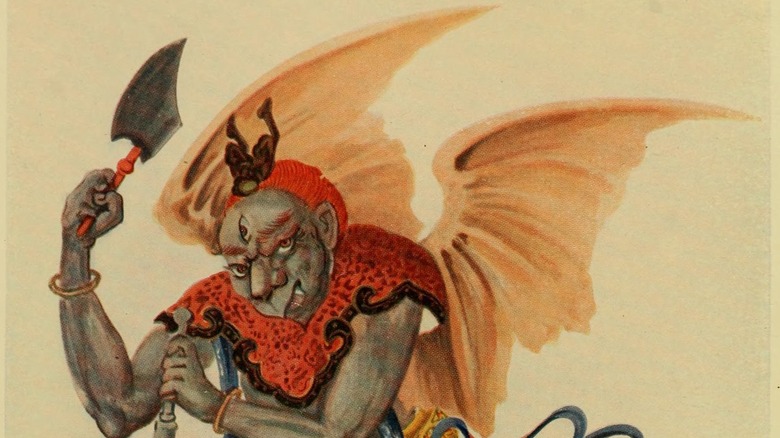

One of the more surly gods in the Chinese pantheon was Lei Gong. His name, according to "Gods and Goddesses of Ancient China," means "Duke of Thunder," and he is also called Lei Shen ("Thunder God"). With bat wings, a blue body, and fearsome claws, Lei Gong was indeed monstrous. Yet this appearance was apt for his divine duties.

When Lei Gong was ordered by heaven, he punished the guilty and creatures who sought to harm humans. How does a god of thunder do this? By thunderbolts of course. Lei Gong used his divine assistants who had control of lightning, wind, and rain to further afflict the sinful. Indeed, Lei Gong was not a Chinese god to mess with. One anecdote, provided by World History Encyclopedia, is that the god noticed that a woman was about to throw out a bowl of rice. Objecting to such waste, he smote her with a thunderbolt, killing her instantly. This woman was judged by the gods to have died prematurely, so they resurrected her to become Lei Gong's helper, who shone light on the target Lei Gong was to smite. It is pretty self explanatory as to why there are few temples devoted to him. However, this doesn't stop believers from uttering a prayer to ask the Duke of Thunder to strike down their enemies.

Chang'e: The Goddess of the Moon

The story of the goddess Chang'e is very well-known in Chinese mythology. Britannica tells us that she was the consort of Hou Yi, a mythical archer who used his bow and arrow to stop plagues and fight monsters including a primordial wind demon. Most know Hou Yi through the various iterations of Chang'e's tale. As told by the "Handbook of Chinese Mythology," in a modern version, Hou Yi was so admired that a god sent to him an elixir that granted immortality. One day, one of Hou Yi's apprentices attempted to take the elixir, but Chang'e swallowed it and fled into the heavens. But she wanted to remain nearby so she chose to inhabit the moon.

A different variation has Chang'e taking the elixir because Hou Yi was exhibiting tyrannical behavior. Thus, she wanted to prevent him from becoming immortal. In this version Hou Yi chased Chang'e to the moon but was prevented from reaching her. She then became the spirit of the moon. Chang'e's festival in mid-Autumn is very popular in China with families laying out mooncakes for the goddess.

Yan Wang: The God of the Underworld

After the adoption of Buddhism, Chinese mythology started to incorporate the underworld. According to "Worship," the underworld was the yin world, which, ghost-filled, was in opposition to the yang world of the living. The greatest lord of this world was Yan Wang, who was its chief judge.

World History Encyclopedia tells us that Yan Wang, who was also called Lord Yama King, judged the souls of the dead. These souls were collected by his servants who came, like the reaper, when their time was up according to the "Book of Destiny." Some might be so virtuous that they would go on to live as gods. Then others would be reincarnated to return to the world of yang. Others had various degrees of sinfulness that they would be punished accordingly. In this last bit, the god relied on scrolls that cataloged every sinful deed a person had done in life. Thus, in traditional Chinese religion, to worship and sacrifice to Yan Wang was to take a proactive and practical approach to avoid an early death.

Guanyin: The Goddess of Compassion

Guanyin is a goddess of the Chinese pantheon who originated in India as the Buddhist goddess Tara. As explained by World History Encyclopedia, this popular goddess came into being from the tears of a bodhisattva and became his companion. The goddess was introduced to China over the Silk Road during the Han Dynasty and took on the name Guanyin.

While, as detailed by Britannica, the goddess originally was portrayed in a masculine fashion, by the 11th century C.E., she had metamorphosed into a beautiful woman. Guanyin also took on mortal incarnations to experience humanity. As World History Encyclopedia details, in one form, she ended up being executed by her father, and then when she arrived in hell, she unleashed all of goodness inside her. Hell became a paradise. The lord of the underworld, Yan Wang, definitely had a problem with this so he kicked her out as quickly as he could. Guanyin then ended up living on Fragrant Mountain to watch over humanity. In particular, she could see those who were in peril at sea and send help to them. As such, she has become the patron saint of those who work at sea.

Erlang: The Demon Queller

The god Erlang Shen started his existence as an object of cult worship which, as related by "The Zoomorphic Imagination in Chinese Art and Culture," was denounced by the Song Dynasty. However, the god grew in popularity.

Erlang was unique. As described in "A Brief History of the Immortals in Non-Hindu Civilizations," he possessed a third eye in the center of his forehead that saw the truth. He was also known as the greatest warrior of the gods and thus has been called the "Demon Queller" among other titles. To help him, Erlang also had a hound called Tiangou, which as described by World History Encyclopedia, he used to pursue evil spirits. Other details on this god are provided by "The History of Customs in Song, Liao, Jin, and XiaXia Dynasty," which include how he was not just a warrior, but a water god who engineered waterworks. Erlang Shen's festival was highly popular in ancient China and still is so today.

Caishen: The God of Wealth

One god of the Chinese pantheon that is still venerated today for the most practical and obvious of reasons is Caishen, the god of wealth. Britannica gives two origins to the god. In one instance, Caishen was originally a hermit named Zhao Gongming who used magic to support the Shang Dynasty but then was slain by magic instead. Since Zhao was virtuous he became Caishen. In another version, Caishen started as a man named Bi Gan who was executed by the last Shang emperor.

Whatever the origins, Caishen is popular during the Chinese New Year in which he is honored in the hopes of bringing wealth for the coming year. World History Encyclopedia explains that Caishen is usually depicted as a statue of a rich man bearing wealth or sometimes with attendants following him carrying bowls of gold. Caishen though isn't just a god of material wealth but also of having a rich life. In this respect, while Caishen was popular among the merchant class, he was also popular among all classes, with temples to him being the most numerous in traditional China.

Lu Ban: The God of Carpentry

Lu Ban was the god of carpentry and as relayed by "Chinese Mythology A to Z," by Jeremy Roberts, was a high-functioning celestial bureaucrat. He headed the celestial ministry of public works. One story about Lu Ban summarizes his skill and character. As a young man he built a kite. This kite could stay aloft for days and is considered the progenitor of all kites. But it was so powerful that his father took it and used it to fly. Apparently, his father landed in Wuhai where the residents there, seeing a man flying through the air, were justified in thinking that a demon was upon him. They promptly killed Lu Ban's father. This incensed Lu Ban, so to avenge his father he built an immortal out of wood, which then caused a drought in the town.

"Advances in Mechanisms, Robotics, and Design Education and Research" relates that Lu Ban was so skilled that he built a wooden horse carriage that moved without human control. Lu Ban is, in fact, based on perhaps a real inventor from the fifth century B.C.E. whose skill was such that he inevitably became an object of legend.

Zao-Shen: The Kitchen God

Perhaps the most ubiquitous of gods in China was and is Zao-Shen, the Kitchen God. Britannica tells us that name literally translates to "god of the hearth," which is a better description of Zao-Shen since his duties expanded beyond the culinary. But his usual dwelling place was above the kitchen stove as a paper image, thus Kitchen God is the more common name for him.

"Ancestral Images," by Hugh D.R. Baker, explains that Zao-Shen had two functions. First, he determined how long each member of the household lived. Second, he sent monthly reports to the local city god as to the conduct of each member of the household. This was capped off with an annual yearly report to the Emperor of Heaven. World History Encyclopedia describes how after giving these reports he was given orders to either bestow fortune or misery upon a household. Perhaps the best analogy for Zao-Shen was that he was an informer as part of a spiritual spy state. Of course Zao-Shen did provide some benefits to the home. He protected the household from ghosts.

To try to get into Zao-Shen's good graces, people would provide ceremonial offerings to the god before his annual visit to the heavens at the Chinese New Year. Typically, offerings of wine, food, money, or other paper items are offered then burned with the image of the god, which is then promptly replaced with a new image.

Tudi Gong: Lord of the Place

The earliest gods in traditional Chinese folklore were the Tudi Gong, which as translated by Britannica means "Lord of the Place," "Earth Lord," or "Earth God." There was no single Tudi Gong. Rather, these were gods who inhabited a single location and were ascribed duties unique to that location. This might mean that there was a Tudi Gong for a certain bridge or a public building, or even a home.

Historically, these gods are thought to have originated from actual persons who may have given aid to a community and were deified after death. "Popular Religion in China," by Stephan Feuchtwang, points out that there was no clear cut definition of a Tudi Gong since some could offer protection to entire neighborhoods. Tudi Gongs could be consulted for calendar-restricted activities such as agriculture. Tudi Gongs were also thought to guard graves. In that way Tudi Gongs were thought to be similar to officials that guarded the peace. These were immediately subservient to the next level god, the Cheng Huan, which was a god of a given city. In that way, any given city could have dozens and dozens of local gods.