Messed Up Things That Happened During The Second Mafia War

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the picturesque Italian island of Sicily was ravaged by war. According to Kano, The Second Mafia War, which also came to be known as the Great Mafia War, or Mattanza ("The Slaughter," in Italian), cost the lives of thousands of people. What started as violence between warring organized crime families soon extended into the murder of government officials.

According to Inquiries Journal, the roots of the Great Mafia War can be traced back centuries and can be summed up with a simple phrase familiar to anyone with even a passing familiarity with mafia history: la Cosa Nostra, the name of the Sicilian mafia, which in English means "our thing."

Over the centuries Sicily was invaded by just about everyone at some point, including the Romans, Greeks, and Arabs. This instilled a drive in the Sicilian people to protect their homeland at all costs. This mentality would last until Italian unification in the 19th century, which brought the island under the wing of its closest mainland neighbor, but it wouldn't put an end to the violence.

The death of Stefano Botade starts the war

Stefano Botade (whose surname sometimes appears as Botate) was a powerful and connected figure when it came to the mafia landscape of the 1960s and '70s, and per Italy On This Day. Botade was even believed to have been close to former Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti.

Botade was known as il Falco — which doesn't take much knowledge of the Italian language to correctly surmise means The Falcon — and it was his death in 1981 which is often marked as the event that kicked off the Second Great Mafia War.

Michele Greco, a Mafioso who operated in the Sicilian city of Palermo, and Salvatore Riina, of the Corleonesi crime family, made a pact to work together to take over the heroin trade in Sicily. Greco was known to be a rival of Botade's, but Riina had formerly been an ally.

Botade was assassinated as he drove home for his own 42nd birthday party. The man pulling the trigger was Pino Greco, Michele Greco's nephew and a noted hitman. Riino and Greco also orchestrated the murder of many of Botade's friends and associates. This was a misstep on their part, as it tipped law enforcement off to their involvement, leading to the arrest of some members of their drug trafficking operation.

The assassination of Rocco Chinnici

According to United Press International, on July 29, 1983, 58-year-old Rocco Chinnici left his apartment in Palermo with two bodyguards in tow and headed toward a waiting bulletproof car. Chinnici was the city's chief investigative judge and was known to be tough on organized crime. He wouldn't make it to his car, because a nearby car bomb was remotely detonated, killing him and his bodyguards. Investigators would determine that a green Fiat had been loaded with TNT and parked in front of Chinnici's apartment. The ensuing blast caused immense damage within a 500-yard radius of the epicenter.

It turned out that the assassin who detonated the bomb was Pino Greco, and he had done so under orders from his uncle, Michele Greco, per Inquiries Journal. Unfortunately, attacks like this were somewhat frequent over the course of the Great Mafia War, and this wouldn't be the only time that the name Michele Greco would be tied to such an assassination.

The assassination of Antonio Saetta

According to The New York Times, in 1988, two bodies were found along the road in central Sicily. They turned out to be those of 66-year-old Judge Antonio Saetta and his 35-year-old son, Steffano. The two were on their way home from visiting relatives when they were confronted by men who unleashed a barrage of submachine gun fire on them.

Justice Minister Giuliano Vassalli called the murder of the Saettas "an unequivocal sign of warning and intimidation against the institutions of the state.” According to The Washington Post, Saetta was the eighth judge to lose their life over a 20-year span.

Much like Rocco Chinnici, Antonion Saetta was known to be a judge who was tough on organized crime, and in 1983 he upheld life sentences for Michele Greco and his brother Salvatore for their involvement in the assassination of Chinnici. This once again illustrates the immense power Michele Greco held at the time. He carried the nickname il Papa — the pope.

The Maxi Trials put away hundreds

In the wake of Stefano Botade's assassination in 1981, two of his close associates, Tommaso Buscetta and Salvatore Contorno, became pentiti, which means they started working with the government. They subsequently handed over evidence that would allow Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino to kick off the Maxi Trials (via Italy On his Day).

Falcone and Borsellino were magistrates with anti-mafia views and they were key figures in the trials which began in 1986. They presented over 8,000 pages' worth of evidence which they obtained from pentiti like Buscetta and Contorno. Their efforts managed to convict over 300 Sicilian mafia figures, including both Michele Greco and Salvatore Riina.

The Maxi Trials were the largest mafia trials in history at the time, with a grand total of 338 defendants found guilty, with 19 of them receiving life sentences, according to The New York Times. However, key Cosa Nostra members wouldn't take this blow lightly, and unfortunately for Falcone and Borsellino it meant that there would be a price to pay.

La Cosa Nostra's vendetta against Falcone and Borsellino

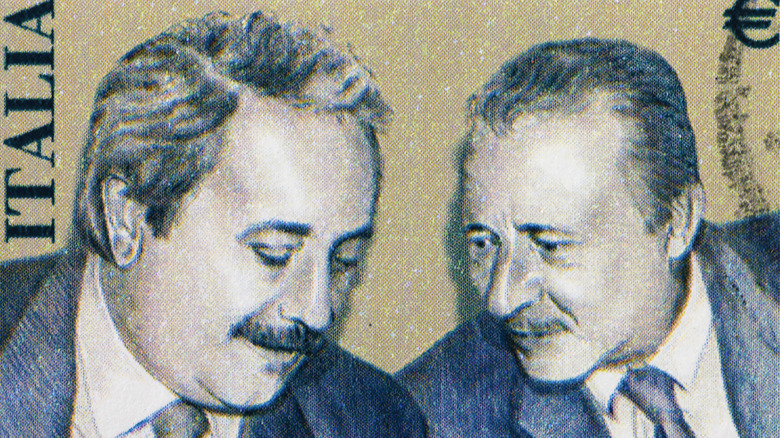

Fighting organized crime can be a dangerous line of work, something both Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino (above) were fully aware of. According to Italy On This Day, special safety precautions were taken by both. They traveled in armored cars and used bodyguards. Falcone even worked in a bomb-proof shelter. Sadly, all these measures would not be enough to keep the two men safe.

La Costra Nostra members fought their Maxi Trial convictions, which were upheld by the Italian Supreme Court in 1992. Four months later, on May 23, Falcone was driving to his home in Palermo when a bomb exploded, killing him, his wife, and three police officers. He was known to travel the same stretch of road en route to his home every week and that led to the placement of the bomb — which had been ordered by Salvatore Riina — and its successful detonation. Falcone would be remembered in a New York Times piece written by his friend Peter Secchia as "the closest thing Italy had to a living symbol of resistance to organized crime." On July 19, Borsellino would also be killed by a bomb, this one planted outside his mother's house, killing him as he left after a visit.