The Mysterious Case Of The Feral Child Victor Of Aveyron

In December of 1798, three hunters in the Tarn region of southwestern France saw what looked like a child dart up a tree. Surprised, the three men investigated and found a naked boy of about 11 hiding from them in the branches of an oak. They called out to him, but he didn't seem to register their words. Somehow they managed to pull him down and carry him into a nearby town, where they entrusted him to an elderly lady. The boy was bizarre-looking. He apparently spoke no language at all, and he had an animal's nervous mannerisms, grunting and refusing to make eye contact.

All this was documented by one Dr. E.M. Itard, who would later take care of the boy. Itard's book, "An Historical Account of the Discovery and Education of a Savage Man" (from 1802, available at Gutenberg) described him as "disgusting" and "slovenly... spasmodic... like some of the animals in the menagerie, biting and scratching those who contradicted him."

Within a week, the boy had escaped the old lady. Nearby villagers spotted him skulking around wearing only the shirt he'd just been given. A clergyman had him captured and sent to Paris, where crowds gathered to see the boy soon to be called Victor of Aveyron, the most famous feral child in France.

Forever a child of the woods

France's National Institute of the Deaf and Dumb took an interest in the strange young boy and had him placed under the care of Dr. E.M. Itard, who named him Victor. Itard studied the boy's habits and concluded that like the earlier Peter the Wild Boy – who was kept as a royal pet — he had lived his whole life as an animal. His body was covered in scars, and although gunshots did not disturb him, his ears pricked at the sound of a walnut shell cracking. He adored walnuts, a taste he may have owed to the acorns and wild nuts he ate in the woods (via History).

Itard attempted to teach Victor to speak, but the boy never quite caught on. Slowly, Victor learned to bathe, dress himself, show affection, and recognize certain French words. Nevertheless, he could not get the boy to speak more than a few grunted syllables. He never learned to say his own name.

Was this the "blank slate?"

Victor's discovery could not have been better timed. Since the middle of the 18th century, wild children and "savage" cultures had achieved a kind of cult status in Europe. British, American, and French explorers had finally come into contact with cultures that had not developed the same social and technological sophistication as Europe, India, China, and other settled civilizations. Exotic lands like Tahiti, the Edenic backdrop of the Bounty mutiny, seemed to be a remnant of mankind's childhood.

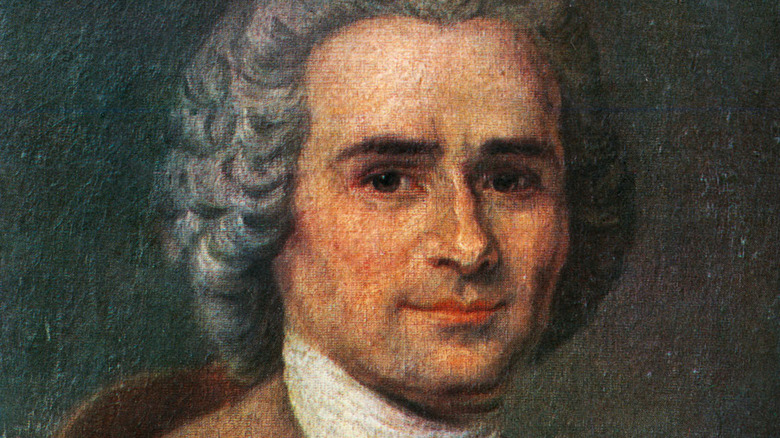

French philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau (seen above) were convinced that Western civilization was a kind of fall from grace. Man was born noble and good, went the general drift; owning property and commanding others, fundamental to civilization, was what turned people wicked. In England, John Locke had argued that the human mind was a "blank slate" at birth, created by the culture around it (via Britannica). These intellectuals pored over the world looking for examples of the "noble savages" whose "slate" had not been corrupted.

Victor of Aveyron was one such "noble savage," and Itard's book says explicitly that the boy represented a chance for science to explore how a mind becomes civilized. Perhaps it was inevitable that such an optimistic experiment would fail. Victor would die at 40, still non-verbal, his identity still unknown.