The Untold Truth Of Vercingetorix

The most powerful leaders of the ancient world combined military prowess with political cunning and a hefty dose of megalomania. Most benefited from royal bloodlines springing from so-called divine sources. For example, Alexander the Great's human parents were Philip II of Macedon and Queen Olympias, but some claimed his real dad was none other than Zeus, the god of thunder (via History).

Other rulers whose names have stood the test of time include Nebuchadnezzar, Ramses, Pericles, and Julius Caesar. Each of these men made a name for themselves through political cunning, military conquest, and exemplary duty to country. As victors on the battlefield, they also had a say in how the historical record would remember them.

But not all great and heroic leaders have enjoyed such luxury. Consider Vercingetorix, ruler of the Arverni and arch-enemy of Julius Caesar. History hasn't treated him as kindly as his nemesis, despite the war chieftain's valiant service and selfless sacrifice on behalf of his tribe. While Vercingetorix remains a national hero in France (per the Irish Times), his legacy proves tenuous outside the Francophone world. And the few primary historical sources describing his life and deeds come from his enemies. Here's what you need to know about this unsung hero of the Celtic world.

Vercingetorix had all the makings of greatness

The name "Vercingetorix" doesn't necessarily roll off the tongue, but this Gallic title came with great honor. It translates as "victor of a hundred battles" (via World History Encyclopedia) and remains the only name recorded for the Gallic chieftain. Undoubtedly, he also had a birth name, but the members of his tribe kept it well hidden. Like other Gallic tribes, Vercingetorix's kin proved a superstitious lot. They believed knowing a person's birth name granted certain powers over them.

The other information we have about Vercingetorix proves scant, but the few ancient writers who described him lauded his towering height and rugged good looks. We can also assume he wore long hair and a mustache based on Gallic fashion of the time and a few coins bearing his image. True to his title, Vercingetorix rose through the ranks from a celebrated warrior to king of the Arverni and general of the confederates, according to Britannica.

Vercingetorix and his tribe fell under the larger auspices of the Celtic tribes, located in modern-day France's central region of Auvergne, per Britannica. The Arverni held this territory throughout the second century B.C. until 121 A.D., when Roman legions invaded. But the tribe would not face any culture-altering threats from Rome until the 50s B.C. and the advent of Julius Caesar.

He fought alongside Julius Caesar to expel German invaders

Long before Julius Caesar's Roman legions came on the scene, the Gallic tribes united in the fourth century B.C. to siege and sack Rome, per the World History Encyclopedia. But they'd since found few reasons to cooperate. As one of the Celtic world's largest and most powerful tribes, the Arverni allied with many smaller Gallic tribes, particularly against their age-old enemy, another Gallic tribe known as the Aedui. The Aedui took a similar tack, fortifying their army with sympathetic neighbors. Eventually, they counted the Romans among them. One of Gaul's greatest weaknesses would prove its unwillingness to unite as one people, especially against the Romans, until it was almost too late.

When Germanic tribes, including the Helvetii, flooded across the Rhine and made incursions into Gaul, it altered the chaotic status quo of the Gallic tribes forever. Caesar ruled in neighboring Hispania (modern-day Spain). A clever tactician, he utilized the Germanic advance to impose greater control over what would become Provence in southern France. But before he showed his hand, Caesar allied with the Gauls. The wily general even enlisted the help of the Arverni to drive out the German invaders.

After successfully repelling the Germanic tribes, the Gauls returned to life as usual. But Caesar had other plans. Ever seeking to expand and fortify his power base, Caesar made his next aggressive and unwelcome move.

He and Caesar became arch enemies

Along with his Arverni brethren, Vercingetorix fought with Julius Caesar and his Roman legions to expel the invading Germanic tribes, according to the World History Encyclopedia. The Gallic chieftain led cavalry units for Caesar, and he didn't let these experiences go to waste. Instead, he learned valuable insider lessons about Roman war strategies and tactics that would serve him in future conflicts with Rome.

The figurative straw that broke the camel's back when it came to Gallic-Roman relations would be Caesar's ambitious cultural conquest of Gaul. After pushing the Germanic tribes back, he set out to consolidate Roman power in the Gallic region through systematic enculturation. By imposing Roman law and culture, Caesar transformed Gaul's status into that of a conquered nation. This betrayed the Gallic mercenaries who had so recently allied with Rome. But Vercingetorix didn't rebel first. Instead, it fell to the chief of the Eburones, Ambiorix. In response, Caesar led his legions mercilessly against the tribe, massacring them en masse, enslaving the few that survived and burning their tribal lands.

Caesar sought to make an example of this rebellious tribe, inadvertently inciting the scorn of Vercingetorix. In Book VII, passage IV of Caesar's memoirs, he notes that Vercingetorix's decision to take up arms led to his expulsion from the Arverni town of Gergovia by his uncle Gobanitio who feared Roman reprisals. But Vercingetorix continued to assemble forces, soon returning to seize the village and assert his kingship over his people.

Vercingetorix was a soldier on a mission of vengeance

Vercingetorix found himself in a game of catch-up, according to "Delphi Works." Julius Caesar had nearly completed the subjugation of the Gauls, which began with the invasion of the British Isles, the center of Celtic religious beliefs. Having put the Druids on notice and effectively cut off from their Gallic adherents on the Continent, Caesar moved in for the kill with only Vercingetorix and the forces he rallied to oppose the legions.

According to World History Encyclopedia, Vercingetorix represented more than Caesar's nemesis. He also sought retribution for the evils done to the Eburones. But not all Gauls agreed with his stance and solution. A meeting of the tribal council revealed the elders didn't have the stomach to go up against Caesar. Nevertheless, Vercingetorix threw caution to the wind, overriding the tribe's other authorities and singlehandedly launching a challenge against Rome.

In 52 B.C., he led forces against Cenabum, a Roman settlement. After massacring Roman loyalists, he seized the city's food supply and weapons, redistributing them to the Gallic people whom he hoped would ally with him. He also sent messengers throughout the Celtic world, advertising his victory and asking them to join his cause. Many responded positively, swelling Vercingetorix's ranks. War History Online observes, "It is a tribute to the skills of Vercingetorix that he united so many Gauls in the face of Roman aggression."

He dealt the Romans a major defeat before succumbing at Alesia

A defeat of the Gauls at Noviodunum Biturigum appeared to support the elders' belief that opposing the Romans represented an impossible and potentially disastrous endeavor (via Britannica). But Vercingetorix refused to admit surrender. Instead, he harassed Caesar's forces by attacking supply lines via guerrilla warfare, and he also tempted the Romans to engage on terrain favorable to the Gauls.

Among Vercingetorix's military advantages was his cavalry, which outmaneuvered the Romans at every turn, as reported by World History Encyclopedia. He also conducted a scorched earth policy, including burning bridges, severing supply lines, and demoralizing Roman soldiers. Vercingetorix had one goal: to obliterate any resources the Romans might use to their advantage. The Gauls obediently complied with his orders until he suggested dismantling Avaricum, a city of 40,000, to ensure the Romans couldn't profit by taking it. The Gauls pleaded with him to keep the settlement intact, which Vercingetorix eventually did. But as the Gallic chieftain had predicted, Avaricum would eventually fall to Rome with little more than 800 residents escaping the ensuing massacre.

As news of the horrors of Avaricum spread, Gauls came out of the woodwork, joining Vercingetorix's army to seek revenge against the Romans. This surge of new blood contributed to the Gauls' victorious seizure of Gergovia. They repelled Caesar's legions, forcing the Romans to flee. But the Gallic chieftain's stroke of luck couldn't last forever.

He sacrificed himself to save his people

After leading a failed counteroffensive of 80,000 Gallic troops against Julius Caesar, Vercingetorix and his men retreated to the fortress of Alesia, per World History Encyclopedia. Likely located in Eastern France, Alesia marked Vercingetorix's final stand (via Britannica). Caesar placed his 60,000-strong army around Alesia, laying siege. He also brought in a German mercenary cavalry to challenge the Gauls.

According to Britannica, Julius Caesar set up siege works to attack Alesia while simultaneously ordering his army to build a second defense wall preventing reinforcement attacks from other parts of Gaul. Soon, Caesar had Alesia in a vise. As starvation set in, Vercingetorix dispatched horses and troops to seek assistance from other parts of Gaul, but most got squashed by the Roman forces encircling the city. He also sent out the women and children, hoping the Romans would permit them safe passage. But Caesar's lines held fast, trapping and starving these non-combatants between the Roman and Gallic frontlines.

After one more attempt to break through Roman lines by Vercingetorix's cousin Vercassivellaunus (crazy names ran in the family) and additional troops, the Arverni king saw the writing on the wall, according to Book VII, passage LXXXVII of Caesar's memoirs. D.H. Lawrence described Vercingetorix's grandiose surrender to Caesar: "A chieftain in splendid glittering armour, with plumes waving from his helmet, bracelets of gold on his arms, his horse shining with silver and coloured cloths ... It was Vercingetorix yielding himself up to save his beleaguered men."

Vercingetorix faced prison and public execution

D.H. Lawrence's account describes Vercingetorix surrendering, and this version is backed by the ancient author Cassius Dio, per World History Encyclopedia. But a second account disseminated by Caesar claims the other Gallic chiefs in Vercingetorix's army betrayed him, turning him over to the Romans to save their necks.

Either way, Dio claims that observers within the Roman camp felt shocked by the presence of the imposing warrior who knelt in defeat before Caesar. The historian noted, "Many of those watching were filled with pity as they compared his present condition with his previous good fortune." After leading Vercingetorix away in chains, the Romans massacred the remaining defenders of Alesia, ensuring the Gallic world's complete submission.

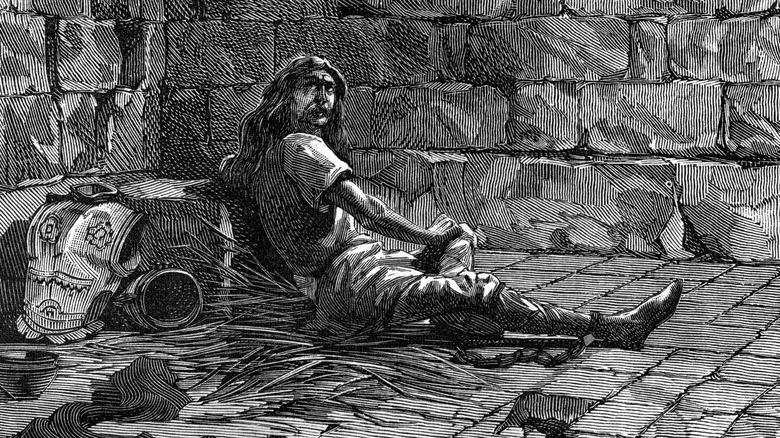

Transported to Rome, Vercingetorix languished in the infamous Tullianum dungeon for six years (via Haaretz). This prison contained the highest value prisoners in the Roman Republic as they awaited presentation in triumphal processions. After that, most prisoners faced strangulation, execution, or starvation. And Vercingetorix would be no exception. The once-proud leader faced a humiliating march in the first of Caesar's four triumphs in 46 B.C. before public execution (via Britannica).

Much of what we know about Vercingetorix comes from the Romans

Apart from some coins bearing the likeness of Vercingetorix, most of what we know about this famed warrior comes from his arch-nemesis, Julius Caesar (via The Encyclopedia of Ancient History). Of course, the historical accuracy of Caesar's accounts of Vercingetorix prove dubious. As Cambridge points out, Gauls like Vercingetorix "have been made to speak as the conqueror wished them to speak. To think as the conqueror desired them to think, even sometimes to act as he would have had them act."

Although Caesar did give Vercingetorix some admirable qualities, he selected them strategically to puff up his own reputation. After all, to be great meant conquering great enemies. But Caesar also went to tactical lengths to paint Vercingetorix as brutal. For example, in Book VII, passages IV-V of his memoirs, Caesar recounts how Vercingetorix inspired an army to march with him. Instead of flowery speeches and appeals to freedom fighting, the Roman general claims Vercingetorix "collected an army by their punishments." He explains, "To the utmost vigilance he adds the utmost rigour of authority; and by the severity of his punishments brings over the wavering."

These punishments included having ears chopped off or eyes gouged out, rendering Vercingetorix more of a psychotic madman than a liberty-seeker. Unfortunately, Caesar's portrayal of the Gallic chieftain remains largely unchallenged because of a dearth of other historical sources. The picture we have of Vercingetorix today reeks of propaganda and incompleteness.

He remains France's first national hero

The ancient Romans wouldn't be the only group to appropriate the image of Vercingetorix for political reasons (via "Vercingetorix, Asterix and the Gauls: Gallic Symbols in French Politics and Culture"). France transformed the Gallic chief into the nation's first national hero, according to "'Our Ancestors the Gauls': Archaeology, Ethnic Nationalism, and the Manipulation of Celtic Identity in Modern Europe." Revising how the French viewed Vercingetorix began as early as the mid-19th century.

Napoleon III erected an impressive monument to Vercingetorix in 1865 at Alise-Saint-Reine, per Art & Architecture, declared Alesia by 19th-century archaeologists. During the two World Wars, Vercingetorix took on a new role in French national identity. After all, these conflicts pitted the French and their allies against the Germans, recalling the final betrayal of Vercingetorix by Germanic mercenaries allied with Caesar at Alesia. It led military heroes like General Charles de Gaulle to declare Vercingetorix "the first resistance fighter in [France's] history," as quoted in "Vercingetorix, Asterix and the Gauls."

But there are at least a couple of problems with co-opting Vercingetorix as a national hero. For starters, French culture and language owe as much (if not more) to the Romans as the Gauls, per "A Characterization of Gallic Latin." What's more, as the BBC ironically points out, had the Arverni prevailed against the Romans, the Germanic tribes likely would have overrun Gaul once more, rendering France a part of Germany.

There's an asteroid named after Vercingetorix

Despite living thousands of years ago, Vercingetorix's memory still burns brightly in the night sky as Asteroid 52963 Vercingetorix, per The International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center situated in the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

Having an astronomical phenomenon named after Vercingetorix proves poignantly fitting. After all, the Celts had sophisticated beliefs about commemoration after death and the afterlife, which required proper burial with myriad grave goods (via World History Encyclopedia). Gallic tribes like the Arverni saw these rituals as vital to a hero's smooth transition into the Otherworld.

To them, the Otherworld ultimately represented a place very much like the material realm but liberated from the heartache of pain, disease, sorrow, and mortality. To reach it, the soul must leave through the head, helped along by the prayers and sacrifices of the living. Of course, the Romans denied Vercingetorix these final rites (via Haaretz). Where the Celtic Otherworld existed, no one knows. But there's something poetic about the Gallic leader's name permanently written in the heavenly realms through an asteroid naming ceremony.

France's Asterix and Obelix comics commemorate Vercingetorix

"Asterix and the Chieftain's Shield" is a popular edition of an iconic French comic book series that explores Vercingetorix's final stand, per the BBC. In a snarky twist, the comic book shows Vercingetorix throwing his weapons and armor aggressively onto the feet of Julius Caesar rather than in front of him (via The Guardian).

From there, the tale presents a whimsical and tongue-in-cheek look at France's Gallic past. Besides the apparent exaggerations and comedic elements, this comic series has done an excellent job of enticing the French people into learning more about Vercingetorix and France's Celtic legacy. According to the Irish Times, the popularity of the Asterix and Obelix comic books demonstrates just how vital the Gauls remain to France's national identity.

Rene Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, the creators of Asterix, thinly veiled the historical figure of Vercingetorix in their rendition of Asterix. That said, the brave and plucky main character proves relatively short compared to his real-life counterpart. But, in other ways, the literary mirroring runs deep. The Irish Times (quoting Le Figaro) argues, "Asterix corresponds to the consensual image that the French have of themselves." In other words, there's a little piece of Vercingetorix in the heart of every French person.

Controversy remains about the actual site of Alesia

In 2012, the Alesia MuseoParc opened in the village of Alise-Sainte-Reine in northern Burgundy. This area has long held the reputation for being the ancient site of the hill-fortress of Alesia. The museum does an impressive job of teaching visitors about the lifestyles and fighting techniques of the Gauls, and it cost an estimated €75 million to construct (via the BBC).

There's just one problem with its geography. A growing number of scholars believe Alise-Sainte-Reine has little to do with the Gauls, Vercingetorix, or the battle for Alesia. The comic "Asterix and the Chieftain's Shield" alludes to this with a running joke that no one knows where Alesia is. How could a site so important to France's heritage up and disappear? Some believe the Romans wanted it this way. After the siege of 52 B.C., they razed Alesia to the ground, leaving few traces of the once-populous citadel.

Of course, it hasn't helped that the French government and the academic establishment have long thrown their weight unquestioningly behind Alise-Sainte-Reine. Even though another site, Chaux-des-Crotenay near Geneva, fits Julius Caesar's description of Alesia to a tee. If and when archaeologists finally take Chaux-des-Crotenay seriously, it could yield a wealth of new information about France's first resistance fighter, Vercingetorix.