This Is Why US Presidents Can Only Serve Two Terms

The office of the American presidency and the executive power it affords were always seen as a looming potential threat by the men who established it. Dubbed "the fetus of monarchy" (via Presidential Studies Quarterly), even proponents of a strong executive branch forever tiptoed carefully around the shadow of King George. How many years can one president stay in office without becoming corrupt? How many terms should a president serve? Up until the time of Franklin Roosevelt's re-election to a third term, the unwritten "two-term tradition" had been modus operandi for the most part. Yet in the shadow of Roosevelt's 12-year presidency, legislators gathered to draft a constitutional amendment codifying this tradition in law (via Politico). The debate, however, goes back much farther than that.

In the dusky, rheumatic halls of the Philadelphia statehouse, a coalition of heavy drinkers (per Huffpost) had recently overthrown a government. In the absence of their now-dismissed aristocrat King George III, the men were tasked with the momentous feat of deciding what, exactly, would take his place.

It was 1787 at the Constitutional Convention, according to Britannica, and well-to-do white men were dispensing lengthy rebukes of their colleagues and delivering passionate speeches with arguments of their own. It was brutally-contested policy territory for detractors of every faction, The members needed to decide how presidents should be elected, and they needed to decide how long a president could serve before he was liable to see himself a king.

Delegates, despotry, and debate in Philadelphia

The men with the quills who would write these laws and etch out the conditions of the presidency were well aware of the importance of minutiae. One ill-constructed preposition or omitted clause could embolden any number of potential future despots.

Alexander Hamilton, a young lawyer and rising political star, argued that the president should be elected by Congress every four years, with unlimited chances at re-election (according to Federalist papers No. 71 and No. 72, via Library of Congress) — a system George Mason dubbed an "elected monarchy" during a debate at the 1788 Virginia Ratifying Convention (via University of Chicago). "I would not trust a prince," he continued, once again invoking the specter of King George. Thomas Jefferson, for his part, expressed concern that his colleagues' admiration for Washington was translating into problematic policy (via the Library of Congress' Jefferson Papers). Among Hamilton's opponents, many shared a strong conviction that the presidency should be limited to one term of seven years, according to Mental Floss.

'I would not trust a prince': emerging from the shadow of the monarchy

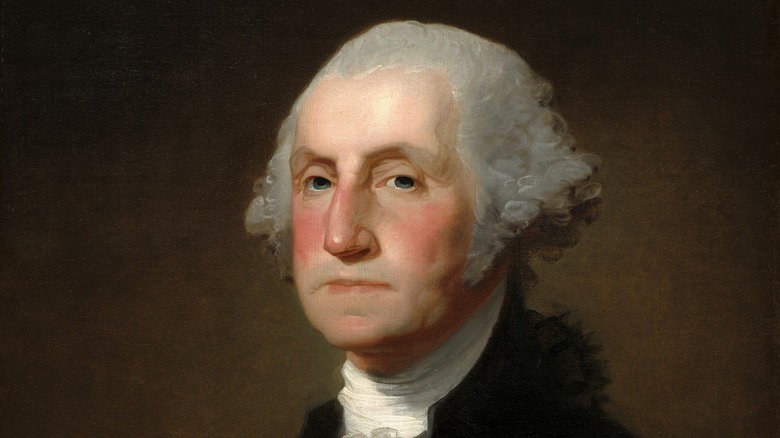

In the end, the limit of a presidential term was set at four years. Presidents could, however, be re-elected as many times as they could win. Elections would be decided by a vote among pre-selected delegates belonging to the newly-devised "electoral college" (via History). The first election under this system was held in 1789, according to Britannica. It was universally understood that George Washington would win — and he did, of course. At the time of Washington's election, no term limit had been established.

After serving two terms as president, Washington declined to run for a third. Perhaps accustomed to the obligatory mythologizing of aristocrats, Washington's contemporaries (and later, their political progenies) enshrined the Virginia slaveowner in a godlike legacy — he was the man who "surrendered" the presidency rather than forge it into a seat for kings (as seen in The Washington Papers via the National Archives). At some point, it was decided that if Washington himself did not dare serve three terms, it would be strictly inappropriate for anyone else to do so (as Mount Vernon proudly reported). Thus the "two-term tradition" was established in practice. It wasn't until Franklin D. Roosevelt won his third election that anyone dared to break it.

How a George becomes a law

Congress passed the 22nd amendment in 1947. It was ratified In 1951, limiting presidents to no more than 10 years or two elected terms (per the National Constitution Center), enshrining this decorum in law.

Although both Ulysses S. Grant and Theodore Roosevelt made bids for a third term in office (unsuccessfully, as Peabody noted), no president prior to FDR had ever served three terms. In fact, several presidents, including Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, and William Henry Harrison had all publicly advocated in favor of setting constitutional limits on the number of terms a president can serve (per Peabody). It wasn't until Lyndon B. Johnson took office, however, that an attempt to set re-election limits succeeded. With the exception of a relatively low-stakes push to overturn it by Ronald Reagan in 1987 (according to the The New York Times), there have been few (if any) serious attempts to challenge the Twenty-Second Amendment since its passage. Limits on re-election are most likely here to stay. Our despots will have to corrupt our government by other means — a dilemma we can perhaps circumvent entirely if we would simply not elect them in the first place.