The History Of Roman Triumphs Explained

Ancient Roman society was a brutally competitive and often deadly battle of all against all for power and status, best captured in one ancient value: "dignitas." This was a measure of clout in this patrician society, and no honor conferred more dignitas than the ritual parade following a great military victory — the triumph.

Every elite Roman grew up in a house with the dead faces of their ancestors staring back at them. The Roman "death mask" was a wax imprint made during the life of an aristocratic male. These sleeping ancestral faces, eyes closed for the cast, lined rooms built as shrines to remind young Romans where they came from and the heroic deeds they were expected to emulate. Romans weren't just in a competition with their contemporaries, they contended with their own forbearers too. A successful military venture, culminating in a ceremonial triumph, assured any citizen vaunted immortality.

As per Britannica, Roman consuls, who were also often generals, were elected among a senatorial class, so warriors and politicians were one and the same. These consuls were a rough equivalent of an American president, though two were elected at a time for one-year terms only. These often dueling commander-in-chiefs would then actually lead armies in the field. This meant a lot of Romans were walking around with credible military and political dignitas to spare. The way to stand above them all, past and present, was to win conquests so large, they demanded the grand fanfare of a state-sanctioned triumph.

Roman triumphs come from Greek myths

The first triumph was supposedly held by the mythical namesake of Rome, Romulus, who may or may not have ever existed. The story is laden with legend, so things were probably hazy even to first century B.C.E. citizen-historians like Livy, who gives us our best account.

Romans professed to believe their twin founders, Romulus and Remus, were cast out during a family feud in a small Italian kingdom called Alba Longa. King Amulius had just usurped his big brother Numitor and now wanted future rivals gone too. Numitor's daughter, Rhea, had somehow hooked up with the god Mars and bore him divine twins, Romulus and Remus. God-princes whose grandfather was a deposed king would certainly have a great claim to the throne, and Amulius ordered them tossed into the Tiber River. As luck would have it, they washed ashore near the future site of Rome, where they were suckled by a she-wolf and a woodpecker, according to Britannica.

Herders found the boys, and they grew up strong and took revenge on Amulius but had a falling out themselves. Remus was killed, and Romulus had his new city named after him. According to Villanova University, the Roman writer Pliny believed Romulus' eventual inauguration of the triumphal tradition of military parades came from Bacchus, the Roman god of fertility, agriculture, and wine — all the makings of a good party. Bacchus himself, however, was derivative of the Greek god Dionysus, another notable party monster.

The first triumph was a celebration of successfully abducting women

After Romulus ascended to the throne of his titular cit,y he realized he had a big problem. This band of merry men lacked something crucial to sustaining itself: women.

Unable to lure local ladies to marry Roman men with ordinary enticements, Romulus invited the neighboring people of Caenina and other nearby communities to a special summertime festival of Neptune Equester, according to the Italian Art Society. But, it was all a trap. The "eligible" women were abducted in an incident known to history as the "Rape of the Sabines."

The Roman historian and Julius Caesar contemporary Livy says a group of young Romans were hand-picked to "carry off the maidens who were present ... some particularly beautiful girls who had been marked out for the leading patricians were carried to their houses by plebeians told off for the task." Horrified by this plot, the neighboring King Acron launched an attack on Rome. Romulus and his forces counterattacked and soon defeated the aggrieved king.

Romulus celebrated this victory with the first-ever triumph on March 1, 752 B.C.E. The first-century Greek historian Plutarch recounts in his opus "Parallel Lives" that the Roman king cut down an oak to wear a laurel wreath on his head -– an honor the balding Caesar later enjoyed for his own triumphal celebrations. Romulus had truly set the precedent: "His procession was the origin and model of all subsequent triumphs."

You had to kill a lot of people to get a triumph

The Romans killed a lot of people, and they were brutally efficient in their craft. In 73 B.C.E. a massive group of slaves and dissidents banded together in a force of some 70,000 strong and defeated a regular consular army in open warfare during a two-year conflict known as the Third Servile War, according to Britannica.

Several Roman generals were sent in to quell this uprising, but it was Julius Caesar's legendary rival, Pompey Magnus, who swooped in at the last second to join general Crassus and crush the rebellion. The men bickered for credit. According to Plutarch's "Parallel Lives," Cassius killed 12,300 while Pompey slew 5,000. The minimum to earn a triumph was 5,000, notes Britannica.

But the rules for earning a triumph weren't hard and fast. Technically, the honor was reserved only for consuls or praetors, and you had to be in your 40s for those high offices, according to California State University. Years earlier, Pompey had earned his first triumph in his mid0-20s, notes Hermes, and he wasn't a consul or praetor (via Plutarch's "Parallel Lives"). Nonetheless, in 73 B.C.E., a 33-year-old Pompey was also coming off a wildly successful campaign in Spain, according to Plutarch, and was awarded his second triumph. The triumphal honor was foremost an expression of political power, so carnage was a necessary legal prerequisite, but certainly not decisive.

Triumphs were about showing off your swag

The decline and fall of democracy in ancient Rome has been blamed on many things, but the city-state's sudden wealth and deep inequality have emerged as a popular parallel for contemporary social issues.

In 146 B.C.E. Rome concluded nearly 100 years of wars with neighboring Carthage, known as the Punic Wars. As History details, led by Scipio the Younger, the grandson of legendary Punic War veteran Scipio Africanus, Carthage was annihilated, and 50,000 of its citizens were sold into slavery. Once a regional republic, Rome became an unchecked empire that stretched from Spain to modern Turkey. It had accumulated "wealth on an unprecedented scale," according to Mike Duncan, writer and podcast host of "The History of Rome and Revolutions" (via Smithsonian Magazine). "You're talking literally 300,000 gold pieces coming back with the Legions. All of this is being concentrated in the hands of the senatorial elite ..."

Historians like Duncan have long noted that this inequality dispossessed lower-class Romans of their land and contributed to the political turmoil that upended the republic. Ancient Roman leaders were perhaps too busy parading their personal spoils during triumphs, and according to Livy's "The History of Rome," even passed-over plebs loved the show. "The spectators were not more interested in the scenic representations and the athletic contests and chariot races than they were in the display of the spoils from Macedonia. These were all laid out to view — statues, pictures, woven fabrics, articles in gold, silver, bronze, and ivory wrought with consummate care, all of which had been found in the palace ..."

Prisoners of war were paraded through Rome

Triumphs were, optically at least, ostentatious displays of splendor, but the ultimate spoil was a foreign sovereign who had bent the knee to Rome.

Prisoners of all ranks were paraded through the streets during the Republican period and would routinely be executed at the finish of the procession, according to The Collector. So legendary was this practice, Cleopatra supposedly killed herself with the bite of an asp rather than fall into the hands of Augustus at the end of the Roman civil wars in 30 B.C., as per History.

Three centuries later, queen Zenobia also displeased Rome and found out how bad this could be. The republic had long since become an empire and was going through a rough patch. In the interim, Zenobia ruled an ascendant Palmyra (modern-day Syria). When Rome regrouped, Emperor Aurelian smashed the queen's forces in A.D. 272, as The Collector details. Zenobia was paraded back to Rome and "publicly humiliated throughout the east." Aurelian displayed her in his triumph as well, according to The Collector. Some historians claim she was beheaded or even starved herself to death to avoid further humiliation, a la Cleopatra, but her ultimate fate is unknown.

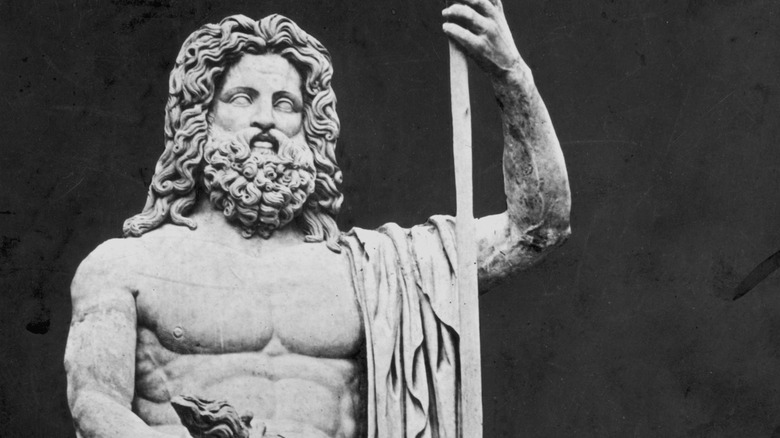

Roman generals were gods for a day

The conquering general at the center of a Roman triumph was very much a god for a day. They often had their faces painted red with vermilion, according to Vintage News. This was symbolic of Mars, the god of war, or even Jupiter, the king of Roman gods. The temple of Jupiter in the heart of Rome was the endpoint of a triumphal procession and where a bull (and some prisoners) would be sacrificed in a bloody climax.

The most interesting part of a triumph though was the Roman tradition of reminding a conquering general that they are not actually a god. Perched behind a general in the triumphal chariot would be a slave, holding a wreath above the hero's head, repeating this reminder, "memento mori" — Latin for "remember you will die," according to Classical Wisdom, or better, "remember, you are mortal," as per Vintage News.

This stoic incantation became customary as the ambitions of Rome's generals threatened the republic's stability. Julius Caesar had long flirted with immortality — one extant inscription carved during his lifetime named him the descendent of Ares and Aphrodite, according to Bart Ehrman, professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Upon his assassination in 44 B.C.E., the Roman state assuaged the grief of ordinary citizens and made his deification official, a first in Rome, notes the BBC. When Caesar's adopted son and successor, Octavian, became Rome's first emperor, he naturally assumed this status as well. The triumphal reminder of "memento mori" had not been sufficient.

The lesser version of a triumph: the ovation

Let's say you couldn't kill the requisite 5,000 for an official triumph. You could still throw yourself a smaller party for your lesser victory: the golf-clap level ceremony known as an ovation, according to the World History Encyclopedia.

Sometimes this triumph-lite was in order when the enemy was not considered a worthy opponent. Roman society was an honor culture, and there wasn't much cache in dispatching pirates, for example, or worse, slaves. Despite the fact slave revolts were a legitimate existential threat to the republic — proven over the course of three bloody Servile Wars – the Roman General Marcus Licinius Crassus was denied a triumph when he put down the legendary uprising by Roman citizen-turned-dissident, Spartacus. In such borderline cases, the pomp was turned way down: There was no chariot ride, the consul would ride horseback or walk, a sheep would be sacrificed, and sometimes the consular army wouldn't even participate.

On occasion a winning general would be denied their triumph and celebrate on their own time. After the assassination of Julius Caesar, his top commander Mark Antony took up with Cleopatra in Alexandria as one-third of the hotly anticipated sequel to Rome's original ruling trinity, this one called the Second Triumvirate. The brash and flamboyant Antony eschewed convention when he held a smaller triumph in Alexandria in 34 B.C.E. –- an act Rome's traditionalist elite considered to be quite gauche.

Pompeys' lavish two-day triumph

If you want to understand the vibe of a Triumph look no further than Pompey the Great's spectacular third Triumph in 61 B.C.E., as per Britannica.

Pompey entered the city wearing Alexander the Great's cloak, according to the A.D. second century Greek historian Appian. This was a spoil from Pompey's total victory against King Mithradates in Anatolia. As he paraded his vast army through the city in full regalia, perched atop a chariot "studded with gems," all the pageantry of Rome would have been on display as the city's denizens flocked to see the first Roman general to earn a triumph from conquests on three different continents.

Pompey paraded enemy troops through the streets but did not put them to death, as was custom, again notes Appian. He sent them back to their native countries at "public expense." Two foreign kings who were brought as props for the ceremony were not so lucky, however, and were killed on the sacred Capitoline Hill. Pompey's exploits were also featured in huge paintings on display for the procession. He had brought to Rome millions of gold coins, dwarfing the sum in Rome's already substantial public coffers. This two-day party was so overstuffed with loot and pageantry, "much of what had been prepared could not find a place in the spectacle," according to Plutarch in his biographical opus, "Parallel Lives."

Julius Caesar was the king of triumphs

Julius Caesar was famous for kicking butt and maxing out his credit card. While celebrating four triumphs over a period of weeks in 46 B.C.E., Caesar put on a spectacle for the ages including "an elephant fight with twenty beasts a side, and a naval battle with 4,000 oarsmen plus a thousand marines on each side to fight," according to Appian (via National Geographic). Caesar also awarded his loyal soldiers in gold, handing out a sum "far beyond what they would have earned in a lifetime." For ordinary Romans, he "gave a magnanimous sum of 400 sesterces to every citizen, distributed food, and staged gladiatorial combats and athletic events."

Caesar earned his first two triumphs with victories in Gaul and Pontus –- the latter site where he uttered the famous line, "I came, I saw, I conquered." His third triumph was for his mastery of Africa. During the fourth triumph for his victory in Egypt, Caesar displayed the captured sister of Cleopatra, but when the crowd showed sympathy for the chained woman, he spared her life.

Caesar did however make a PR misstep while celebrating his victory over Pompey. Technically, defeating other Romans wasn't cause for celebration. Caesar was careful not to display images of the still-popular Pompey, notes Appian, but Pompey's dead allies were depicted. This historic fourth triumph inflamed political tensions in Rome, and Caesar would be assassinated by some of his closest friends just two years later.

The triumphs of the great emperors

The exact date of the death of the Roman Republic is hotly debated, but the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C.E works. Even though the general ultimately subverted democracy in naming himself dictator for life, he was arguably the last leader of Rome actually elected. But even if democracy fell, the triumphal tradition partially endured into Rome's long imperial period.

Caesar's adopted son Octavian Caesar kept the legacy alive with his own triple triumph in 29 B.C.E., according to Acta Classica. Octavian won a great victory in the Balkans, but more importantly, defeated his Second Triumvirate ally Marc Antony at Actium and Alexandria. Smashing Antony and Cleopatra's army left Octavian the sole ruler of Rome, and his triumph signaled the new imperial era. Caesar's son began calling himself Augustus, meaning "sacred" and "grand."

Records of triumphs under Rome's emperors are patchy. The last triumph in the close Republican tradition perhaps belonged to the emperor Vespasian and his general Titus, for their victories in the Jewish Revolt. Celebrated in A.D. 71, a Jewish general who defected to the Roman side left the most detailed description of any triumph: "Spectators could see a mighty quantity of silver, gold, and ivory, formed into all sorts of shapes ... they flowed along like a river" (via "Spectacles in a Roman World," by Siobhan McElduff). Haggard prisoners on display were even dressed in fine clothing to hide the "deformity of their bodies."

The slow death of the triumph

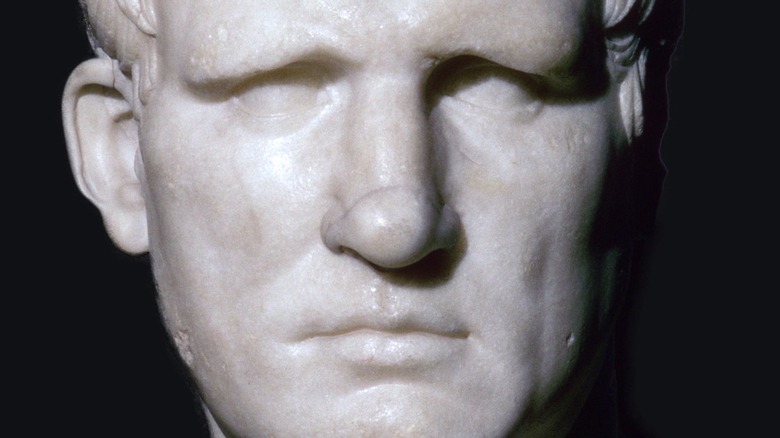

The man who had actually won the Roman civil war was Octavian's brilliant general, Marcus Agrippa, but he did not celebrate any triumphs. Rome's rulers would let democratic formalities exist as a fiction but were no longer letting popular generals threaten the new unitary power structure. The last triumph recorded in Rome's official "Fasti Triumphales" was in 19 B.C.E., and all subsequent triumphs would be in the name of the emperor, according to The Collector.

The change happened when Agrippa first refused a triumph in 37 B.C.E. because he didn't want to "upstage" Octavian, notes The Collector. Agrippa again refused a triumph in 19 B.C.E. for his pacification of the Iberian Peninsula –- a feat that brought about the Pax Romana, 200 years of relative peace. Agrippa's unusual humility also demonstrates his genuine bond with Octavian/Augustus, surprising among the state's normally hyper-competitive elites. Augustus even named Agrippa his successor in 23 B.C.E., and it would actually be Agrippa's ancestors who would rise to ultimate power –- including the infamous emperors Caligula and Nero.

The last arguably traditional triumph in the Republican tradition was held for emperor Theodosius the Great, who fought off a usurper named Magnus Maximus in A.D. 389, according to The Collector. Much later, when Rome was the Byzantine Empire, the last triumph of any kind was held in A.D. 534 in Constantinople for a general named Belisarius.

Triumphs come to America

Though the triumph would continue intermittently throughout the imperial period, the bloom was off the rose. Without the fierce democratic competition of those halcyon republican squabbles, triumphs became sort of like a Super Bowl parade held in honor of NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. Maybe he's doing a great job, but nobody owns his jersey.

The triumphal legacy fittingly though found a rebirth in Renaissance art. Interest in the tradition re-emerged in 1550 when fragments of the aforementioned list of triumphal honorees were rediscovered, known as the "Fasti Triumphales," according to The Collector.

A victorious Napoleon was fascinated by antiquity and recreated a triumphal procession featuring loads of stolen loot during a long march back to France in 1806. He is also depicted in paintings borrowing the style of figures from ancient Rome –- the same way Julius Caesar fetishized Alexander or the very gods to whom he claimed familial relation. The most enduring modern legacy of triumphs today is found in classically inspired architecture. Triumphal arches like the iconic Arc de Triomphe in Paris, ordered by Napoleon, owe fully to this fascinating tradition. Similar arches can be found in London, Pyongyang, and New York -– the grand aesthetic having traveled all the way from antiquity to the new world.