Advice We Learned From U.S. Presidents That You Should Totally Avoid

It's no secret: Being the president of the United States gives someone a pretty significant pulpit from which to preach. This was not lost on President Theodore Roosevelt who famously referred to the presidential stage as his bully pulpit. Today, tens of millions of people tune in for the State of the Union address every year (via Statista). Words of presidents are read and recited in schools. Some quotes, such as John F. Kennedy's famous "Ask not" moment, are etched in the nation's collective memory.

Many past presidents have also used this world stage to shell out advice. These presidential tidbits of wisdom have often been meant to guide and inspire. For instance, George Washington once wisely advised that you should only associate with people "of good quality" as it is "better to be alone than in bad company," as per Mount Vernon. Thomas Jefferson famously stated that when one was angry, it was wise to count to 10, but if one was very angry, it was best to count to 100, according to Henry S. Randall's "The Life of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 3" (via Monticello). Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted a graduating class of college students to know that life was not about "making your way in the world" but "remaking the world which you will find before you," as per the University of California, Santa Barbara.

As poet Alexander Pope once wrote though: to err is human — and, of course, presidents are human. As such, it is likely no surprise that not all advice given by U.S. presidents has been top notch. In fact, some guidance suggested by presidents had been outright bad.

Millard Fillmore

TIME Magazine once ranked President Millard Fillmore as one of the 10 most forgettable presidents. While his presidential library would probably like to change that, it might not be so bad if people forgot some of his advice as president.

It was October 1850 when Fillmore wrote a letter to Daniel Webster, his secretary of the state, stating that he detested slavery on a personal level. Still, Fillmore argued, he had little room to act against the institution as president, as its protection was guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. He feared the fight against slavery would destroy "the last hope of free government in the world," he claimed, then added that slavery was "an existing evil, for which we are not responsible, and we must endure it."

Fillmore wasn't incorrect about the limits of his presidential power, but advising Webster that one must endure existing evils, particularly those one is not personally responsible for, is surprising advice from a president. It doesn't help Fillmore's argument that, when he had the power to demonstrate his constitutional authority against slavery with a veto, he chose not to and signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 into law, making it even more difficult for those fleeing bondage to escape through the North.

From this, one learns that advice often falls flat when it comes from someone who demonstrates inconsistent principles.

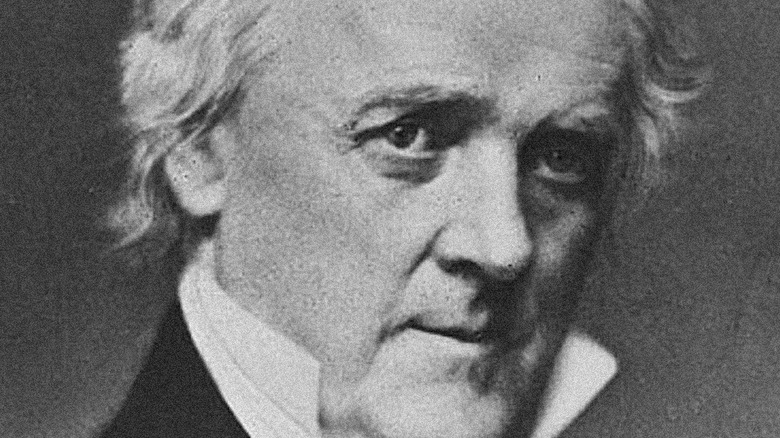

James Buchanan

During the presidency of James Buchanan, it seemed increasingly likely that the U.S. was headed towards civil war. In 1859, some newspapers were already discussing whether or not a civil war had already begun. One then might have expected the chief executive of the U.S. to use his words to calm tensions between the states and unite those who were in disagreement over how to move the nation forward. Instead though, Buchanan advised a tense and uneasy nation in his 1860 State of the Union address that they should not rely on his presidency for such things.

"It is beyond the power of any president, no matter what may be his own political proclivities, to restore peace and harmony among the states," Buchanan declared (via Teaching American History). While he was attempting to justify his inability to find compromise between the states, his proclamation that his presidential pulpit couldn't be used to influence peace further spiraled the country towards war. According to Britannica, Buchanan was unable to deal with the slavery crisis and the growing hostility between the North and South because he was essentially inept at mediation and lacked judgment.

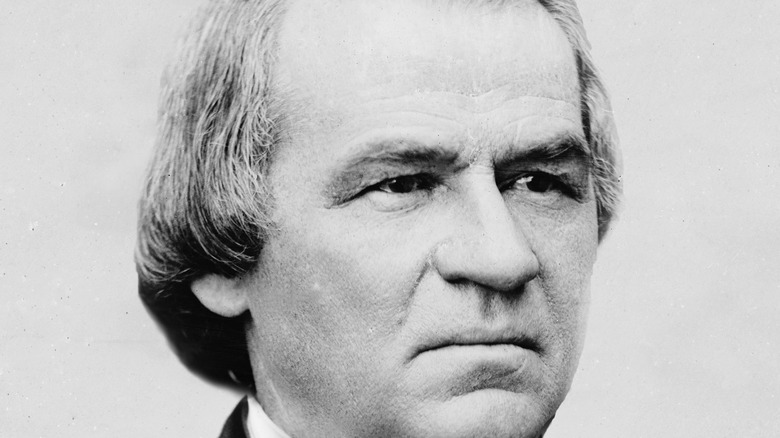

Andrew Johnson

The Department of Justice describes the presidential pardon as "an expression of the President's forgiveness." Following the Civil War, a newly sworn-in president would sign such a presidential pardon, and its expression of forgiveness was, in many ways, also his misguided message to a shattered nation still unsure how to move forward.

The Civil War ended on June 2, 1865, with the surrender of the last of the Confederate forces, as per History. Less than two months prior, President Abraham Lincoln was dead by an assassin's bullet (via History), and Vice President Andrew Johnson, a southern Democrat who had remained loyal to the Union and joined Lincoln on his National Union Party presidential ticket in 1864, assumed the presidency.

It took only a little over a month before Johnson issued a widespread pardon to most white southerners who had rebelled against the U.S. government. The text of his pardon (via the Library of Congress) stated that he "grant[ed] and assure[d] to all white persons who have, directly or indirectly, participated in the existing rebellion ... a full pardon." While the pardon may not have been direct advice, his signature next to those words signaled a clear message: all should be forgiven of those who rebelled. He further demonstrated this by authorizing these newly pardoned white southerners to set up new governments with few conditions. The result of his forgiveness? As described by the University of Houston, all white legislatures took control, locked free Black citizens out of the process, and immediately enacted Black Codes that would eventually usher in a century of Jim Crow in the South.

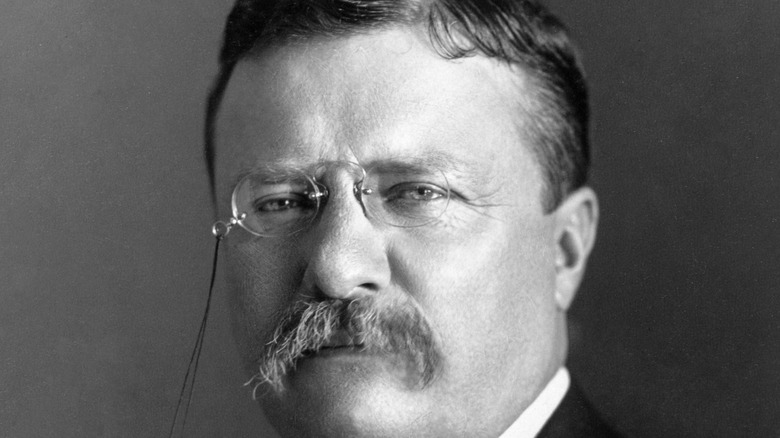

Theodore Roosevelt

One of the more tragic ideologies to spread widely throughout the U.S. during the early 20th century was the pseudo-scientific movement of eugenics. Eugenics, which Merriam-Webster defines as the "practice or advocacy of controlled selective breeding of human populations (as by sterilization) to improve the population's genetic composition," was embraced by many influential and well-known figures of the day, including John D. Rockefeller and Alexander Graham Bell, notes The New Yorker. Another supporter was a former president who had entered back into the political arena with the formation of his Progressive "Bull Moose" Party in 1912: Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1913, Roosevelt wrote a letter to one of America's most prominent eugenicists, a zoologist named Charles Davenport. In it, Roosevelt advised quite clearly that Americans should embrace the Eugenics Movement. "[S]ociety has no business to permit degenerates to reproduce their kind," Roosevelt said. "It is really extraordinary that our people refuse to apply to human beings such elementary knowledge as every successful farmer is obliged to apply to his own stock breeding" (via the American Philosophical Society). He further argued that society should not "permit the perpetuation of citizens of the wrong type" and compared human beings having children to cattle, stating that farmers only allowed their "best stock" to breed, and humanity should apply to same standard to human procreation.

This movement led to thousands of forced sterilizations in the U.S., and in the 1930s it would influence the Nazi Party in Germany, who used the pseudo-science as justification for the horrors of the Holocaust, according to the journal Zebrafish.

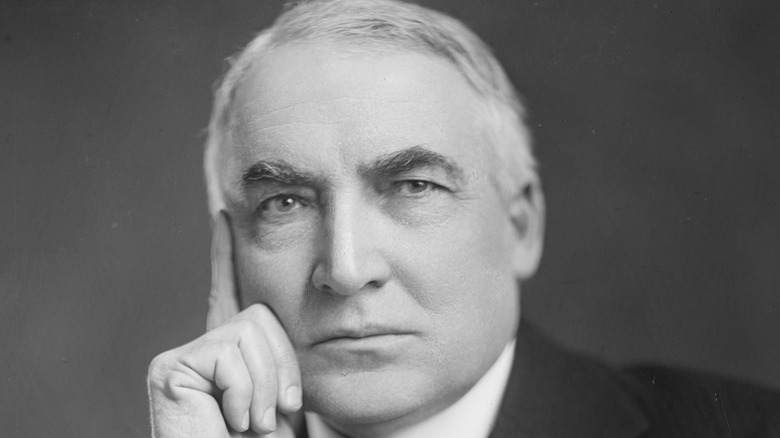

Warren G. Harding

On the presidential campaign trail in 1920, Warren G. Harding, a Republican candidate from Ohio, suggested that with the end of the Great War, America no longer needed "heroics, but healing" (via the White House). While not necessarily bad advice outright, the context it important: Advice tends to ring hollow when the one who gives it — in this case, the man who was about to enter the Oval Office as president — outright ignores it himself.

Instead of working to heal the nation, Harding ushered in an era of distrust of the federal government. By appointing members of his so-called "Ohio gang" to his administration, his presidency faced scandal after scandal, most of which were revealed following his untimely death. According to Britannica, Harding's Ohio gang was a group of politicians closely associated with the president who became known for their scandals including bribery, fraud, numerous conspiracies, and even selling presidential pardons. Perhaps the best known of these was the Teapot Dome scandal, which involved Harding's secretary of the interior, Albert Fall, who secretly leased federal oil reserves for personal gain, illegally enriching himself with hundreds of thousands of dollars.

While Harding may not have been directly involved in most of his administration's scandals, his inability manage those in his circle led to the exact opposite of his advice to heal the nation. Harding himself once said while in office, "I am not fit for this office and should never have been here," according to Nicholas Murray Butler's "Across the Busy Years." Perhaps that was advice worth taking.

Herbert Hoover

It was a year into what would become known as the Great Depression that President Herbert Hoover advised Congress that economic depression "cannot be cured by legislative action or executive pronouncement" (via the U.S. House of Representatives). As it turns out, this was some pretty awful advice. Guided by classical economic theory that capitalist economies were cyclical and would always self-correct, as per the "Encyclopedia of American Business," by Rick Boulware, Hoover did not push for significant relief programs, refused to increase federal spending, and by the time that he recognized his error, he did too little, too late.

According to David E. Hamilton of the Miller Center, "Hoover seemed never to have grasped the grave threat that the economic crisis represented to the nation — and that solutions to the Depression might have required abandoning some of his deeply held beliefs." As a result, the nation plunged deeper and deeper into economic depression, helping inspire economist John Maynard Keynes to theorize that government action was precisely what was needed during such economic crises.

Ultimately, Hoover would pay the political price for his bad advice. In the 1932 presidential election, he was defeated in a landslide by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the governor of New York, who carried 42 states to Hoover's six.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

In 1950, a lesser-known Wisconsin senator named Joseph McCarthy stated he had a list of over 200 registered communists working in the State Department, details the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. By the time of his reelection to the Senate in 1952, McCarthy was one of the most well-known and powerful men in the Senate. He was now the chairman of the Senate Permanent Investigation Subcommittee who was conducting vicious and career-ruining investigations and hearings over what he argued was a communist infiltration of the government.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was no stranger to adversity having been Supreme Allied Commander during World War II, ultimately gave some advice in 1953 on what to do about the rabble-rousing McCarthy: "I really believe that nothing will be so effective in combating his particular kind of troublemaking as to ignore him."

Yet, by Eisenhower advising people to not confront the bully outright, McCarthy was emboldened. By 1954, McCarthy even began going after the military, which ultimately led to the U.S. Army's lawyer climatically declaring to McCarthy, "Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?" (via Britannica). To Eisenhower's credit, he didn't completely follow his own advice: His administration worked behind the scenes to undermine McCarthy, according to the Miller Center. Still, it took a skilled broadcast journalist named Edward R. Murrow who helped reign in McCarthy's power and led to his censuring by the U.S. Senate.

John F. Kennedy

President John F. Kennedy is widely remembered for his memorable words, but sometimes his advice could be a little too open to interpretation. One example was during a news conference in 1963, when he was asked about corporal punishment in schools.

Kennedy said in response, "I would not be for corporal punishment in the school, but I would be for very strong discipline at home so we don't place an unfair burden on our teachers," as per the JFK Presidential Library. While he stated outright that he wasn't in support of schools using corporal punishment, defined by Britannica as "the infliction of physical pain upon a person's body as punishment," the second part of his statement is ambiguous and could be read as an endorsement of corporal punishment being used in the home.

While some might argue that he was simply a parent of his times, we now know better when it comes to discipline within our schools and homes. As recently as 2019, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) concluded that physical discipline actually has a harmful long-term effect on children, including leading to emotional, behavioral, and academic issues. Despite this, the Supreme Court ruled in 1977 that corporal punishment in schools was constitutional, and 19 states still legally permit the practice, according to Social Policy Report.

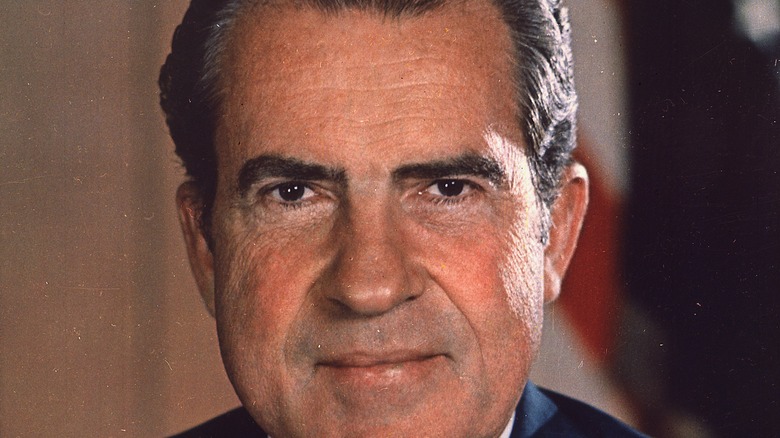

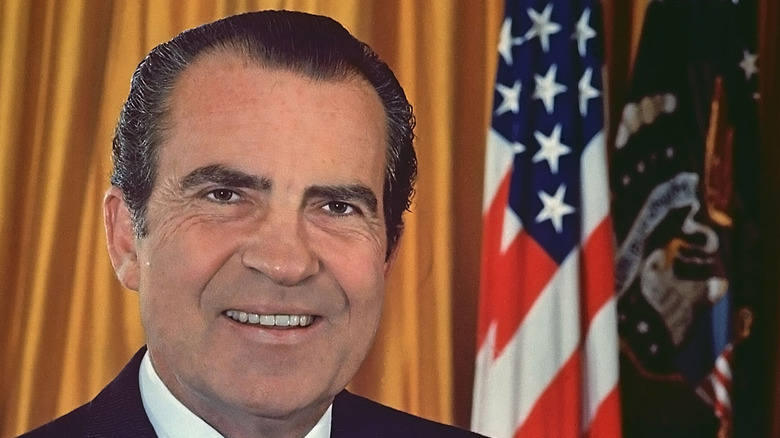

Richard Nixon

Sometimes you simply have to be careful about the advice you give — it just might come back to haunt you. Case in point: Richard Nixon. As the investigation into the Watergate break-in of the Democratic National Committee headquarters began to close in on Nixon's administration, he went on television in November of 1973 to take questions from the press and defend himself. "People have got to know whether or not their president is a crook," he told the American public from a conference room at Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida.

Of course, as history would demonstrate, the American people would soon know whether or not their president was a crook, largely due to journalists such as Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward of the Washington Post who rigorously investigated and reported on whether Nixon had any involvement with the Watergate burglary. Within a year, articles of impeachment against Nixon would be approved by the House Judiciary Committee, as described by History, ultimately leading to Nixon's resignation from office in August 1974, making him the only president to ever resign from office.

In this case, what turned out to be bad advice for President Richard Nixon turned out to be good advice for the American people.

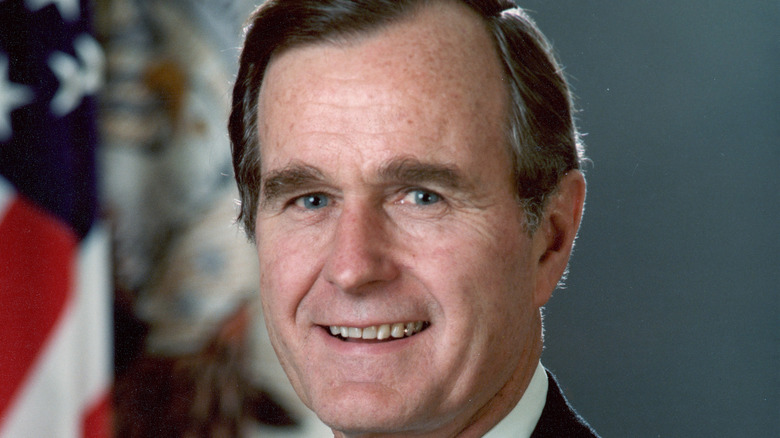

George H.W. Bush

Much to the despair of parents of picky eaters everywhere, President George H.W. Bush once famously implied to children everywhere that rebelling against broccoli was their right ... at least if they were president.

"I do not like broccoli and I haven't liked it since I was a little kid and my mother made me eat it," he said in 1990 (via USA Today). " And I'm President of the United States and I'm not going to eat any more broccoli!" While certainly the comments were somewhat in jest (although he did ban it from Air Force One, according to a 1990 report from the Los Angeles Daily News), some newspapers declared him out-of-touch for his anti-broccoli stance. During the 1980s, broccoli consumption doubled, and the economist for the Agricultural Department even called it the "vegetable of the 80s," according to the Associated Press (via the Gettysburg Times).

Bush's off-hands comments on the popular vegetable also inadvertently started a public feud with California broccoli growers (and, one can imagine, parents at dinner tables everywhere, especially considering how healthy of a vegetable it is). An executive with the Los Angeles-based Fresh Produce Council complained that it was "bad press for the vegetable," as per the Los Angeles Daily News. Fortunately for Bush though, most broccoli growers found the humor in the situation, with one even inviting him to be the grand marshall of a broccoli festival in Greenfield, California, then called the "Broccoli Capital of the World."

The lesson here? Sometimes it's better to keep those controversial food opinions to yourself.

Donald Trump

President Donald Trump made many interesting statements during his four years in the White House. Many of those came from his then-favorite social media platform of Twitter. One of his strangest tweets came in the form of advice as he said was feeling "really good" while recovering from COVID-19 at Walter Reed Hospital on October 5, 2020.

"Don't be afraid of Covid," he tweeted, while still under the care of some of the best medical professionals in the U.S. "Don't let it dominate your life."

His advice for people to not have any fear of COVID-19 was viewed as downplaying the severity of the disease and encouraging in many a false confidence. As reported by the New York Times at the time, one infectious disease specialists stated that his advice would "lead to more casual behavior, which will lead to more transmission of the virus, which will lead to more illness, and more illness will lead to more deaths." At that time, the death toll in the U.S. was around 210,000. He also made these comments before the deadliest of the surges hit, which increased the average of 700 daily deaths from COVID-19 when he tweeted this to nearly 4,000 daily deaths two months later, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.