Who Was Vladimir Putin's Mentor?

To those outside his own head, Vladimir Putin comes across as a tangled mix of obvious yet undecipherable, avoidant yet confrontational, and more than willing to play chess with lives and fundamental human ethics. His reign alone illustrates his tactics: He's been in power since 2000, even when he wasn't Russia's president, because he groomed his successor, Dmitry Medvedev, to re-elect him after term limits forced him to step down (via History Colored).

Putin supports enemies when those enemies' enemies encroach on his territory, such as when he offered the U.S. support following the terrorist attacks of 9-11 (per Chatham House). Yet, he recently declared the independence of breakaway states Donetsk and Luhansk despite those states still being formally a part of another state that he claims is in his territory, Ukraine (per CNBC). On the human-and-animal-rights front, Putin pushed a bill forbidding animal cruelty, down to outlawing petting zoos and animal cafes (per the Moscow Times), but has called teaching about non-binary genders "on the verge of a crime against humanity" (per The Washington Post).

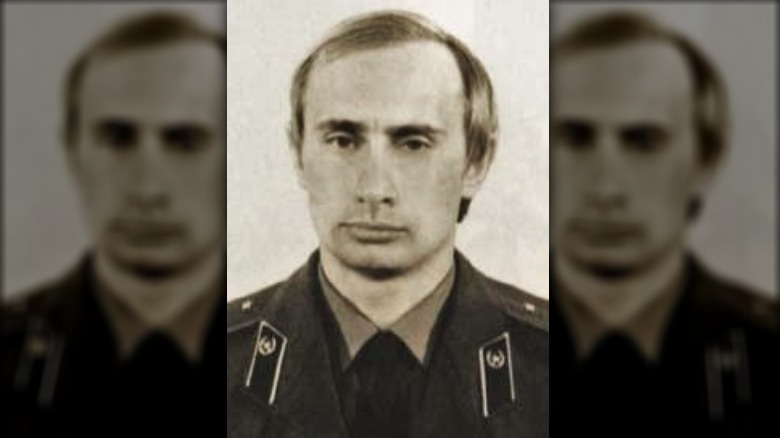

If it seems like Putin's all about manipulation and machination, there's a clear reason. As Business Insider says, he was a spy and a dossier-making KGB agent in East Germany for five years directly after graduating from university in 1975. Yet, in another odd contradiction, his mentor, Anatoly Sobchak, was a staunch, Gorbachev-era believer in free and democratic nations. And over time, as The Guardian relates, Sobchak grew worried about Putin's "authoritarian inclinations."

Beloved icon of democratic government

To be clear: Putin's mentor, Anatoly Sobchak, isn't the one who taught Putin to invade and inveigle. Sobchak was a self-described "radical realist" inspired by Martin Luther King, Jr., as The Guardian recounts. He disliked the use of power, and opposed the forceful overthrow of government. He advocated "glasnot," described by History as the very non-communist notion of extreme governmental transparency. Glasnot, as a principle, took root during the mid-1980's "perestroika," an era of Russian governmental and economic restructuring when leaders such as Mikhail Gorbachev desperately tried to democratize Russia for the modern age.

Sobchak was instrumental in working side-by-side with Gorbachev. They were both despised by Russia's old, backwards-gazing, authoritarian-minded vanguard, but loved by the people. Sobchak was renowned for gifted oratorical skills that made their televised way into people's homes in the evening. In the final days of the U.S.S.R. in 1991, with open conflict brewing between supporters of old and new governments, Sobchak risked arrest to make his way to Boris Yeltsin's side and support Yeltsin's vie for presidency. This was at a time when Sobchak himself was popular enough to be considered a potential presidential candidate. After heading up Russia's largest pro-democracy demonstration since the Russian Revolution of 1917, Sobchak became mayor of his hometown, Leningrad, that same year, in 1991.

Since the early 1970s, Sobchak had taught law at the University of Leningrad. It was there that he'd met his pupil Vladimir Putin, who'd enrolled as a law student.

Mentor and pupil, diverged

The exact nature of Putin and Sobchak's relationship is shielded from history. Judging by available evidence, their relationship might have started as congenial, but diverged as Putin's ideology evolved. Sobchak became increasingly wary of Putin's "authoritarian inclinations." He felt so even as he advocated for Putin on the presidential campaign trail in 1999 at the end of Boris Yeltsin's twin-term presidency (via The Guardian). Sobchak, as a former political leader speaking on behalf of a former pupil, stressed Putin's then-"democratic convictions."

Whether Sobchak's support for Putin's presidency was a glaring oversight, a misjudgment of character, a coerced act, or something else, is unclear. It seems unlikely that a figure as earnestly democratic as Sobchak would have worked to place someone as Machiavellian as Putin in power. We're only left with conjecture, e.g., Sobchak was secretly working with the KGB to undermine Russian economic stability so that a figure like Putin could step into the power gap. (Conspiracy lovers, take note.)

Even from the outside, though, Putin's current inclinations were always on display. While he was spying for the KGB in East Germany, as Business Insider says, he was fantasizing about the power spies have to shape nations. He drew inspiration from the heroic narratives of the Nazi-thwarting film series "The Shield and the Sword." Perhaps Putin cast himself as such a hero, as his recent "de-Nazification" comments regarding Ukraine might indicate (via Vox). Or maybe he's just been lying all along.