The Real Reason We Don't Eat Horse Meat

In Japan they slice it thin as sashimi, to be served raw; according to Voyapon, it's sometimes called "cherry meat" for its delicate color. Sicilians grind it into meatballs or grill it in thin steaks, to be eaten streetside in towns like Catania (via RagusaNews). In Tonga, as Friends of Tonga confirms, it's served in coconut milk. South Germans and Austrians like it as leberkäse, a kind of soft sliced sausage. The French Canadians, like their co-linguists in Europe, relish its dark, mineral savor: Eater Montreal, for example, lists the best restaurants in Montreal that specialize in it.

In horse meat, that is. Horse is one of the most polarizing, widely-butchered animals in the world. Even when observant Jews and Muslims are taken into account (horse is neither kosher nor halal), many cultures worldwide observe a fierce taboo when it comes to horse. English-speaking countries in particular view it as abominable, or at best, as The Atlantic notes, as the miserable food of unsavory foreigners, the famine ration of benighted Europe.

The question is, why is horse meat so polarizing? Is it a matter of familiarity, a vague air of cannibalism, a twinge of guilt surrounding beloved domestic animals? Horses and equestrian sports are as popular in Canada or Italy as in the United States or Ireland. Might it be something older and stranger?

Totems and taboos

The horse meat taboo is old — quite old. In 732, Pope Gregory II wrote to St. Boniface, who was spreading the Catholic faith among the Germanic pagans, "You say, among other things, that some eat wild horses and many eat tame horses. By no means allow this to happen in future, but suppress it in every possible way ... It is a filthy and abominable custom" (per Fordham University). That phrase, "filthy and abominable," implies that the horse taboo was well-established in the 8th century A.D., and restricted to certain cultures but not others.

What is a taboo, after all? What gives certain things their inexplicable sense of holy dread? The philologist and anthropologist Sir James Frazer of Cambridge University (per Britannica) wrote about taboos in his seminal book "The Golden Bough." Frazer was convinced that irrationally avoiding or despising a specific animal was a form of venerating or worshiping it. "All so-called unclean animals were originally sacred," he wrote (via Bartleby). "The reason for not eating them was that they were divine."

The myth never died

Horses were once the object of a related taboo in ancient Britain: It was forbidden to utter their name. The ancient, Proto Indo-European word for horse was likely something like "hekuos," like the Greek "hippos" and Latin "equus," per Harvard University. "Horse," according to Merriam Webster, derives from the word for "run," like "course" or the Italian "correre."

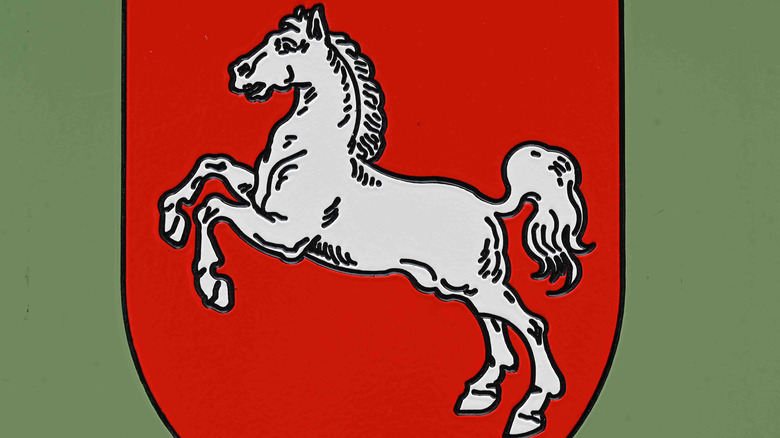

Horses aren't the only object of a naming tattoo — a powerful taboo prohibited cultures all over Northern Europe from pronouncing the word "bear" (via Charlie Russell Bears). But the horse taboo has particular significance for Britain, and by extension English-speaking countries like the United States. According to Joan Turville-Petre, an Oxford University philologist, the legend of twin brothers associated with the founding of nations and with horses exists across the Indo-European-speaking cultures, from India to the Baltic. (Her chapter in the PDF of the "Saga Book of the Viking Society," posted on the website of the Viking Society for Northern Research, begins on page 273.) In Britain, this myth takes the form of the brothers Horsa and Hengist, twin Saxon princes whose names mean "courser" and "stallion." Horses feature prominently in the legends and even the coats of arms of many of old Saxon territories, like Hanover in Germany (shown above) and Kent. St. Boniface, whose congregants still ate horse meat, preached in exactly these regions.

Modern controversies

So is the horse meat taboo a holdover from the pagan past? If so, why don't other countries, who once venerated the divine twins and their horses, observe the same taboo? The Atlantic argues that it was a question of pragmatism: Continental Europeans began to overlook their old taboo in the early modern period out of pragmatism, while the British could source enough beef and so didn't need to.

By the 1890s, rumors of horseflesh passed off as beef were raising old fears in meatpacking cities like Chicago. Americans briefly swallowed their ancestral horror during the food rationing of World War II, but only ate horse as long as they absolutely needed to. The Atlantic notes that "horse meat" became a political epithet after the war.

In the 1970s, the Bureau of Land Management began selling the wild mustangs they culled in the deserts of Nevada and California to meat wholesalers in Canada and Mexico. In 2006, Congress passed the Horse Slaughter Prevention Act, effectively banning the horseflesh trade in American borders; and while Donald Trump did mull lifting the ban during his presidency, taboo seems to have the upper hand. For the foreseeable future, curious Americans will still need to travel to enjoy this curious dish.