The Murder Of The San Francisco Chronicle Founder Charles De Young Explained

San Francisco in the 1870s was, according to KQED, a city of contradictions. The discovery of silver in Nevada in the late 1850s and the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 led to a financial boom not seen since the early Gold Rush days. Bankers, speculators, and railroad owners got rich quick, and the city's population swelled. A bust soon followed the boom, however. The economic downturn had little impact on the city's elite but hit the working class and poor hard. Jobs were scarce and rents were high. Class and racial conflicts grew, and out of the rising tensions, a new political group, the Workingmen's Party, formed. By the end of the decade, the city was ripe for exploitation by such media men as Charles de Young, the upstart founder of the San Francisco Chronicle, and by populist politicians like Reverend Isaac S. Kalloch.

As noted in "Murder by the Bay," once the city's 1879 mayoral campaign had begun in earnest, it didn't take long for de Young and Kalloch to clash. The publisher disapproved of the politicking preacher's dubious past, and the preacher fumed at the newspaperman's unrelenting attacks on his character. Their very public feud culminated in two equally public assassinations – one successful, one not. In the course of just a few months, it appeared that the beautiful city by the bay had returned to its Wild West roots.

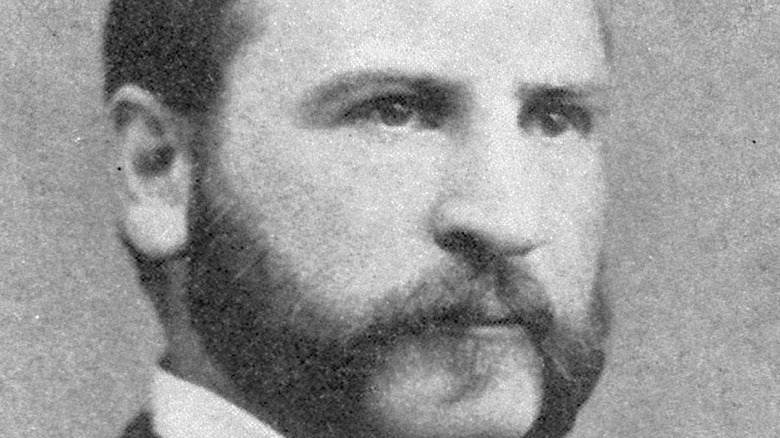

Charles de Young was a teenage William Randolph Hearst

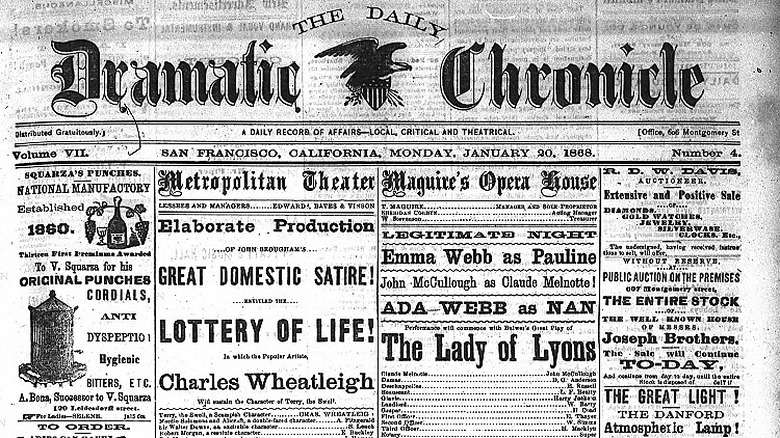

According to Historic Newspapers, Charles de Young and his younger brother M. H. (Michael Harry) launched the Chronicle in 1865 with a $20 loan, when both were still teenagers. (Brother Gustavus briefly worked on the paper as well, according to "Murder by the Bay.") The brothers had already learned the business working at their synagogue's newspaper and applied their knowledge to their new undertaking. Initially titled the Daily Dramatic Chronicle, the 4-page paper billed itself as a "daily record of affairs – local, critical, and theatrical." Its mission was to "enlighten mankind" about the goings-on of "poor mortals here below." Distributed for free in businesses around San Francisco, it was an unapologetic scandal rag.

Under the elder de Young's editorial direction, the Chronicle quickly proved popular and sometimes scooped its rivals for real news. Accusations of bribery, blackmail, and outright lying dogged Charles de Young, but the more salacious and fact-challenged the paper's reporting was, the faster its circulation grew. In time, de Young committed himself to improving the paper's quality, hiring prestige writers like Mark Twain and Bret Harte as contributors. By the mid-1870s, the Chronicle had become high-profile enough to weigh in on elections, and de Young wielded his power as a political influencer with gusto. Not only did he use the paper to endorse and promote favored candidates, but he also used it to demean their opponents, sometimes through innuendo and falsehoods. This practice would soon have unfortunate legal and personal consequences.

Charles de Young was no stranger to the legal system

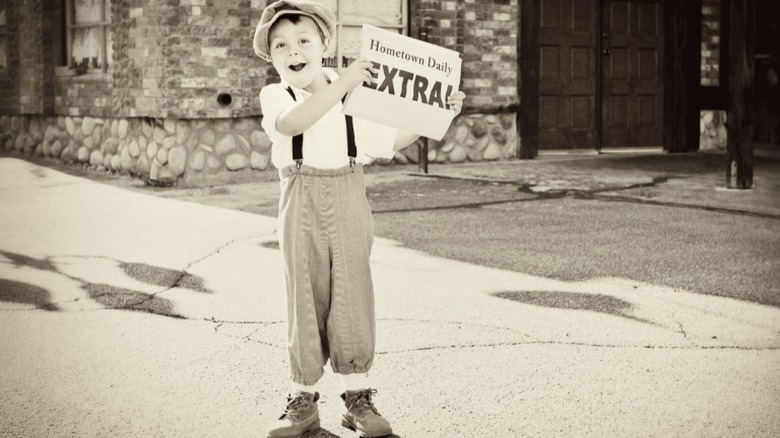

Charles De Young's legal problems began early in his career. According to the Placer Herald, on Christmas Eve 1864, shortly before publishing the first edition of the Chronicle, Charles de Young, his brother Michael, and printer Augustus Henry hired newsboys to peddle "extra editions" supposedly from the city's two most prominent newspapers. The newsboys ran up and down Montgomery Street broadcasting reports about devastating Civil War battles and a local murder. The stories, like the edition itself, were false, and the de Youngs and Henry were arrested for fraud. Charges in the "fake extra case," as it was called, were eventually dropped, according to the Sacramento Daily Union.

Not surprisingly, Charles de Young was sued for libel more than once. In an 1869 case, as described in "Imperial San Francisco," engineer Augustus J. Bowie and his bride, daughter of a wheat tycoon, brought libel charges against the de Young brothers over a story titled "The Course of True Love – Sad Sequel to a Marriage in High Life." The article ridiculed the prominent young couple and described details of their supposed unhappy marriage. A more serious lawsuit was brought against the Chronicle in 1877 by a U.S. Senator and a U.S. Congressman, whom the paper had accused of accepting campaign bribes, according to the Daily Union. The complex case ended in a hung jury in 1878, though as reported by the Daily Union, the Chronicle had provided little evidence to support its allegations.

Charles de Young was quick to shoot but slow to score

As noted in "Murder by the Bay," by the mid-1870s, Charles de Young had earned a reputation for challenging his critics with his revolver but never succeeding in shooting anyone. He was also known to have entered into a friendly quid pro quo arrangement with San Francisco police chief I. W. Lees. In 1875, when de Young heard that rival newspaper The Sun, which had published several scathing attacks against him, was about to print rumors that his mother was involved in sex work, he conspired with Lees to launch a police raid on The Sun's offices. During the raid, de Young and The Sun's editor, Ben Napthaly, exchanged gunfire. Neither man managed to hit the other, but de Young wounded a passing messenger boy.

In 1876, according to the Daily Alta California, de Young's firearm skills were again tested when city resident John Duane, enraged that the paper had called him a squatter, assaulted him. As described by the Alta, de Young "attempted to draw his pistol to protect himself, but Duane disregarded the threatening motion" and knocked de Young to the sidewalk. Duane then grasped de Young's ears and "raised his body several times, and beat his heart against the curbstone, bruising and cutting him shockingly." Stunned, de Young again groped hopelessly for his revolver before fleeing to safety. No complaint was made. As it turned out, the editor was just getting warmed up for a bigger show.

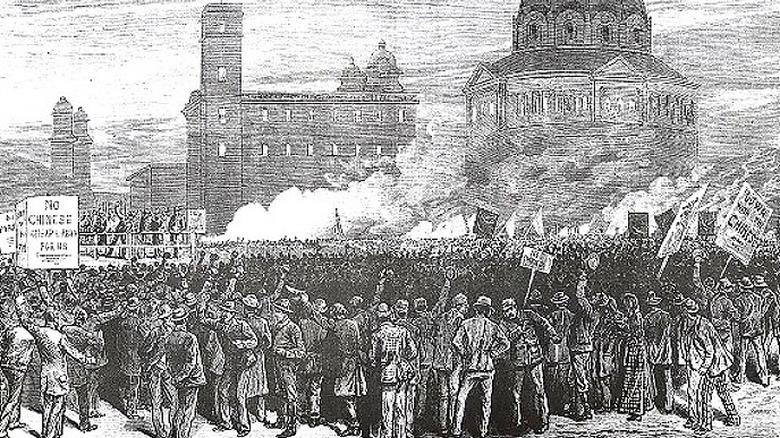

The feuding parties agreed on one thing: their hostility to Chinese immigrants

As noted by KQED, after the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the many Chinese immigrants who had been hired to build it found themselves without work. At the same time, the new railroad brought in streams of other job seekers, and the city's unemployment rate suddenly shot up. The economic bust that followed only exacerbated the already volatile situation. In the struggle to survive, the Chinese bore the brunt of the resentment and were targeted for discriminatory laws and protests.

According to FoundSF, California first enacted anti-Chinese legislation in 1855, and by 1870, "antic**lie" organizations were springing up around San Francisco. City officials enacted ordinances designed to harass and penalize Chinese immigrants, and in 1877, a mob of anti-Chinese protesters tried to burn down the city's Chinatown. To deal with the unrest, business leaders organized their own vigilante group called the Pick-Handle Brigade.

Soon after, Denis Kearney, an Irish drayman and former Pick-Handle Brigade member, founded the Workingmen's Trade and Labor Union, a group that denounced both the rich who employed the low-wage Chinese and the Chinese who worked for low wages. Fueled by the sandlot speeches of the fiery Kearney – which always ended with the phrase "The Chinese must go" – the union group soon became the Workingmen's Party of California. In 1879, the new party, whose platform had received support in the Chronicle, recruited Reverend Isaac S. Kalloch as its first mayoral candidate.

Reverend Kalloch was a man of many preoccupations

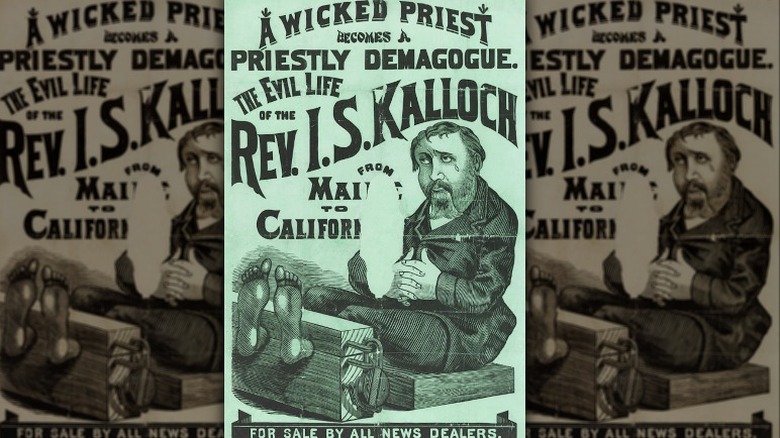

According to The New York Times, Isaac S. Kalloch was born in Maine in 1832 and followed his father into the ministry, eventually serving in a church in Boston. There he earned a reputation as both a powerful, eloquent orator and a relentless womanizer. A supporter of the Know Nothing Party as well as the temperance movement, Kalloch mixed politics with religion and was widely admired by his congregants, especially the female ones. After repeated dalliances, he was indicted and tried for adultery – then a crime in Massachusetts. Although the much-publicized case ended in a hung jury, he was threatened with a retrial and willingly left Boston for Kansas City.

As noted in "Murder by the Bay," Kalloch spent the next 15 years in Kansas engaged in various pursuits, including newspaper publishing, farming, and politicking. He failed at all, while also indulging in drinking, gambling, and of course, womanizing. After another try at preaching, he was again compelled to leave town. According to "Imperial San Francisco," he then landed in San Francisco, where he restarted his life, first as a Baptist preacher, then as a mayoral candidate, running on the Workingmen's Party ticket. Although Charles de Young was generally sympathetic to the new party, he was less than enthusiastic about Kalloch and began running editorials revealing his sordid past as the "Sorrel Stallion." In a city famous for reinvention, the past of Reverend Kalloch was not to be forgotten.

Charles de Young's love for his mother knew no bounds

According to "Murder by the Bay," Charles de Young wasted no time denouncing Isaac Kalloch, referring to him as "depraved," a vile swindler, and a "carpet-bag demagogue." He claimed that the supposedly pious Kalloch had been "observed seducing dozens of women and drinking great quantities of gin in the city's saloons." From his pulpit, Kalloch vowed to sue the Chronicle and shot back that de Young was a blackmailer who had offered to split political spoils with him. The back-and-forth continued over the summer, with Kalloch describing the de Youngs as the "hyenas of society" and Charles de Young daring to expose details about Kalloch's adultery trial. Incensed, Kalloch then condemned the de Youngs as "bastard progeny of a wh***, conceived in infamy and nursed in the lap of prostitution." He also threatened to read aloud the infamous Sun editorial.

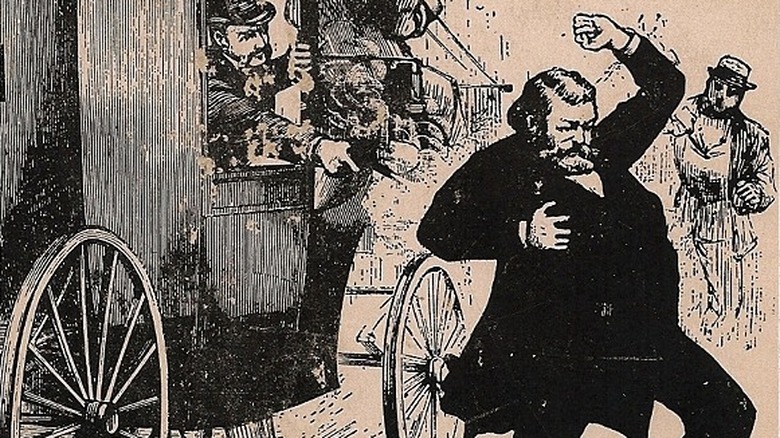

According to The New York Times, Kalloch's threat and public accusation of de Young's mother hit a deep nerve as his "love for his aged mother was something phenomenal." As described by the Sacramento Daily Union, on August 23, 1879, de Young took a carriage to Kalloch's church, then sent a messenger inside to say that "a man" (or according to other accounts, a woman) wished to speak to the minister. From his carriage, de Young then shot the unsuspecting Kalloch three times. Immediately, he was surrounded by a mob but was saved from lynching by Lees' police force.

Was de Young's filial retaliation righteous or cowardly?

As noted by the Sacramento Daily Union, one of Charles de Young's bullets struck Isaac Kalloch in the "breast and another in the thigh." Initial reports suggested that Kalloch's wounds were life-threatening, according to "Murder by the Bay" and the extras of some local newspapers, including the Morning Union, even stated that Kalloch had been killed. By the following day, however, Kalloch was reported to be rallying, with recovery expected. Over the next weeks, newspapers issued regular bulletins about Kalloch's health, sometimes describing his condition as improving, sometimes as worsening. The New York Times noted that members of the Workingmen's Party discussed replacing Kalloch on the mayoral ticket with the group's founder Denis Kearney, in anticipation of the minister not pulling through.

Not surprisingly, de Young's actions were harshly condemned throughout the region. The Daily Union denounced the attack as "revolver journalism" and a "cowardly crime" perpetrated by a "professional newspaper vilifier." The Daily Alta California lamented that the crime would likely damage California's newly won reputation as a law-and-order state. The Chronicle dutifully reported the shooting, but noted that it happened due to an "atrocious slander." According to Guardians of the City, nine days after the attack, de Young received bail and was released from his jail cell, where brother Michael de Young was also being kept for his own safety. Charles de Young then headed to Mexico. Kalloch, meanwhile, was deemed fully recovered by his doctors, and riding a wave of sympathy, was elected mayor in September 1879.

Charles de Young's origin story was complicated

A peek into Charles de Young's family history offers clues as to his motivations, but the view is limited, as many aspects of his biography have been variously reported. As noted in "Murder by the Bay," stories told at the time suggested that the de Young brothers were either descendants of French royalty who hailed from New Orleans, Dutch Jews from Baltimore, the children of Alsatian shopkeepers who emigrated to California to avoid conscription, or the sons of a sex worker from St. Louis. According to "Imperial San Francisco," their father was a Dutch Jewish jeweler and dry goods salesman who traveled frequently but vanished from the scene prior to the family's arrival in California. The de Young family was definitely Jewish, but other facts, such as Charles de Young's birthplace, the source of his mother's money, and his father's fate have yet to be pinned down.

In the end, the de Youngs paid a price for obscuring their past, as the brothers' many detractors felt free to supply their own — usually demeaning — biographical details. Mrs. de Young, in particular, became the target of smears. Although, as noted in a New York Times article, she was "about 80 years of age," de Young's rivals claimed she had been a sex worker and was running a brothel. De Young's attack on the Sun editor had spared her the anguish of reading these accusations, but his attempted murder of Isaac Kalloch laid it all on her doorstep.

Whoso sheddeth man's blood, by man shall his blood be shed

"Murder by the Bay" notes that, in early 1880, upon his return to San Francisco, Charles de Young resumed his post at the Chronicle. Apparently unbowed by his notoriety and Isaac Kalloch's election, he announced that he had sent a Chronicle reporter East to investigate Kalloch's past. According to Guardians of the City, though he expected to stand trial, local prosecutors had delayed indicting him.

As detailed in the Daily Alta California, exactly eight months after de Young had tried to assassinate Kalloch, the latter's son, Isaac M. Kalloch, burst into the Chronicle offices with a five-shooter and started firing at de Young. The first shots were ineffectual, and in between attempts, de Young scrambled to retrieve his revolver from his jacket. De Young was unable to get a firm grip on his gun, however, and Isaac fired another round, which hit de Young in the jaw and lodged in his brain, killing him.

Isaac M. Kalloch was quickly apprehended but refused to explain his motivations. Most assumed he had been agitated by the circulation of a pamphlet detailing his father's adultery trial. Some speculated that by killing de Young before the newspaperman's trial, which had been set for May, Isaac M. Kalloch was assuring the pamphlet and other damning information about his father, including testimony from a woman the Chronicle had purportedly brought in from the East, could not be used in de Young's defense. Regardless of his reasons, Isaac M. Kalloch had murdered his father's tormenter.

De Young got no respect but his paper lived on

As noted in the Daily Alta California, Charles de Young's cold-blooded murder did little to improve his standing with his adversaries. As his body was being taken to the morgue, Mayor Isaac Kalloch's "mob" expressed "fiendish delight" at the sight, and similar "unfeeling and disgusting" sentiments were uttered at "Sandlotters" meetings. While condemning the murder, the local press, according to the San Francisco News Letter and Advertiser (via SFMuseum), was overly zealous in its criticism of the de Youngs and the Chronicle. The New York Times offered a more nuanced summation of de Young's legacy, commenting that "a prominent characteristic of this much-misrepresented man was his intense affection for his mother." According to "Imperial San Francisco," de Young was buried with a pillow embroidered with the phrase "He died for his mother."

Isaac M. Kalloch's murder trial lasted over six weeks, but on March 24, 1881, after a 24-hour deliberation, a jury found him not guilty, to the delight of courtroom spectators, as reported by the New York Times. Powerful testimony by Isaac M. Kalloch sealed the deal, according to "Murder by the Bay," and a prosecution witness who claimed to have seen him fire five shots was later convicted of perjury and jailed.

Despite its ignominious beginnings, the Chronicle prospered under Michael de Young's direction and remains San Francisco's leading newspaper. The elder Kalloch's political career and the Workingmen's Party lasted only two years, as noted by KQED, but California's anti-Chinese laws persisted for many more decades.