Where These Notable Founding Fathers Are Buried

The Founding Fathers of the United States are some of the most studied people in history. You could fill whole libraries with the books that have been written on them, and if you went to school in the U.S. then you will have learned about them in one way or another virtually every year from kindergarten to high school graduation. Their exploits and achievements are held up as the pinnacle of modern governance. And outside of school, you'll even stumble on the fun facts that make these men more human, like the fact that Benjamin Franklin boned seemingly any woman with a pulse.

But rarely does this accumulation of facts include where the Founding Fathers were laid to rest. Maybe because most people avoid thinking about death, unless you live near the grave of one of these men, you probably don't know where most of them are. This is a glaring omission, since some are in unexpected places, have incredible elaborate or surprisingly simple monuments erected over their graves, or had notable funerals that shouldn't be forgotten by history.

While the official list of "principle" Founding Fathers is generally accepted to include just seven guys, according to the American Battlefield Trust, this list includes all of them plus a few other big names who were just as important to the beginning of the United States. Here's where the most notable Founding Fathers were buried.

John Adams

John Adams signed two of the four "founding documents" of the United States (the Continental Association and the Declaration of Independence), was the second person elected to the presidency, and even managed to father another president. He also had a #couplegoals marriage with his wife Abigail.

But death comes to us all, and Adams decided his would be just as awesome as his life. With impeccable timing, he died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the date traditionally considered the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The 90-year-old Adams' last words, according to History, were "Thomas Jefferson still survives." Because he didn't have Twitter to keep him updated on these things, Adams was wrong: Jefferson had died five hours before he did. But news was even slower getting to Adams' own son, the then-president John Quincy Adams. In fact, The Telegram and Gazette reports, the elder Adams had been dead five days before his son even learned he was unwell, let alone that he had died. Indeed, by that point, the former president had already been laid to rest.

The Columbian Centinel (via The National Archives) reported on Adams' funeral in their July 9th edition. While his son might not have been there, it seemed most of the people of Quincy (yes, John Quincy was named after the town) were. John Adams was entombed in a crypt at the United First Parish Church. Eventually, his wife Abigail, son John Quincy, and daughter-in-law Louisa would join him there, per Atlas Obscura.

Benjamin Franklin

Signer of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, Benjamin Franklin might never have become president, but he was important enough to get his face on the $100 bill. After an exciting and eventful life, the Benjamin Franklin Historical Society records he became extremely ill in 1790 from empyema which made breathing almost impossible. He died on April 17, aged 84.

Four days later Philadelphia saw the largest funeral in its history at that point, with a whopping 20,000 people estimated to have attended, out of a population of just 28,000. However, then-President George Washington and members of Congress didn't show up. Franklin was laid to rest in Christ Church Burial Ground, which already held the bodies of his wife Deborah, who predeceased her husband by 25 years, and their son Francis who had died at just 4 years old.

Always a humorist, Franklin had written his own epitaph as a joke way back in 1728: "The Body of B. Franklin, Printer; like the Cover of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be wholly lost; For it will, as he believ'd, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition, Corrected and amended By the Author." While he left instruction in his will for his gravesite and very basic official inscription, this fitting epitaph can now be found on a plaque near Franklin's final resting place. Tourists throw pennies on his grave for good luck.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton might have only signed one of the four founding documents of the U.S. (the Constitution), but his other work for the young country, including his writings on "the doctrine of implied powers," per Britannica, definitely makes him one of the most important Founding Fathers.

Thanks to a 1990s milk commercial (and, in the 21st century, a musical that has done pretty well for itself), most people know that Alexander Hamilton was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr. This meant his death was unlike that of most other Founding Fathers, coming suddenly and unexpectedly. (While his year of birth is debated, Hamilton would have only been in his late 40s when he was killed.) His funeral took place in New York City on July 14, 1804, and the procession was lengthy. The New York Evening Post (via The National Archives) reported "On the top of the coffin was the General's hat and sword; his boots and spurs reversed across the horse. ... The streets were lined with people; doors and windows were filled, principally with weeping females, and even the house tops were covered with spectators, who came from all parts to behold the melancholy procession."

Hamilton was interred at Trinity Church in New York City, and eventually, his grave was marked by a massive monument (pictured), according to the church's official website. His wife would join him there, although she outlived Hamilton by 50 years, and her grave is marked only by a plain stone.

John Jay

While the names of almost all the Founding Fathers should at least ring a bell, John Jay's might not. In fact, "... very few know the full breadth of his accomplishments. Most are very surprised by what they learn," Heather Iannucci, director of the John Jay Homestead says (via PBS).

Jay was indeed a force to be reckoned with. PBS records that John Adams said Jay was "of more importance than any of the rest of us." The CIA recognizes him as "the first national-level American counterintelligence chief." And on top of that, he was the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He died in 1829, aged 83.

If you have a bucket list goal of visiting the graves of all the Founding Fathers, John Jay is going to completely mess up those plans. According to the Journal of the American Revolution, Jay is the only one buried in a private family cemetery, located in Rye, New York. Even more annoyingly, "it is unclear why the Jay family chose to make the cemetery private." The burial ground's official website emphasizes that it is not open to the public, and you can only be buried there if you can prove you are a direct descendent of the Founding Father. But maybe it's as simple as that's what John Jay would have wanted, considering how little he seemed to seek the spotlight when he was alive. As his biographer Walter Stahr put it, "In the end, he's more worried about America than he is about John Jay."

Thomas Jefferson

People's minds are still pretty blown that both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams not only died on the same day but on the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. At the time, people were no less amazed. A statement from the Secretary of War (via the University of California's American Presidency Project) rhapsodized, "A coincidence of circumstances so wonderful gives confidence to the belief that the patriotic efforts of these illustrious men were Heaven directed, and furnishes a new seal to the hope that the prosperity of these States is under the special protection of a kind Providence."

According to Monticello's official website, Jefferson "left explicit instructions" for his gravesite. This included the exact wording for his epitaph, which he insisted "not a word more" be added to. There were only three of his many, many achievements in life that he wanted mentioned: that he wrote the Declaration of Independence, as well as the Statue of Virginia for religious freedom, and that he founded the University of Virginia. You'll notice that list does not include the fact he was the third president of the United States.

Jefferson's funeral was the day after he died, July 5, 1826, and was also to his specifications, which meant he was buried in the graveyard of his estate Monticello, with only a few dozen people attending the simple service. He even asked that his monument be made of cheap stone so people wouldn't be tempted to take it.

James Madison

You know you've had a full life when being president of the United States is just your second biggest career achievement. But James Madison managed to top that by drafting the U.S. Constitution, according to History. He also contributed to "The Federalist Papers," led the country through the War of 1812 (when his wife, First Lady Dolley Madison, famously saved a portrait of George Washington from the White House), and was on the board of the University of Virginia.

Madison was quite long-lived, even by modern standards, making it to 85 years old. The Historic Marker Database says he had outlived all the other Founding Fathers when he died on June 28, 1836, after being bedbound for six months. But the end of his suffering came too early for many Americans, who had wanted him to die on July 4, the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and exactly 10 years after John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died on the same day, per The Miller Center at the University of Virginia.

Madison was buried in the family cemetery at his estate in Virginia, Montpelier. However, despite his importance to the country, his grave was not marked at the time, and indeed it would be 21 years before a monument was added to mark the spot.

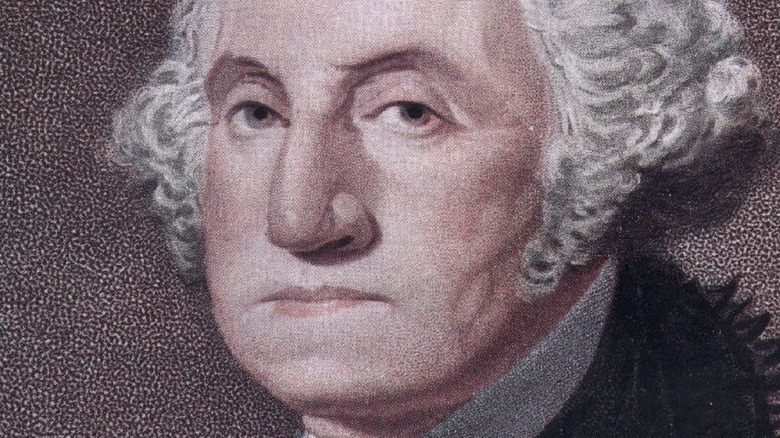

George Washington

George Washington wasn't a young man when he died, but he wasn't that old, and his death at 67 happened so suddenly that the country had no time to prepare mentally for the loss of the victor of the Revolutionary War and their first president or literally for a funeral. According to The Farmer's Almanac, Washington's cause of death was noted at the time as "an inflammatory sore throat, which proceeded from a cold of which he made but little complaint," which historians now think was probably pneumonia or strep. In his eulogy, Major General Henry Lee called Washington, "First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen."

Before he died, Washington left instructions for what to do with his body. Mount Vernon's official site records that he wrote, "The family Vault at Mount Vernon requiring repairs, and being improperly situated besides, I desire that a new one of Brick, and upon a larger Scale, may be built at the foot of what is commonly called the Vineyard Inclosure [sic] ..." Unfortunately, those repairs didn't happen, because politicians planned to ignore his wishes and bury Washington in the Capitol. Until then, they just kept his remains in the rundown crypt, which meant it was easy for a disgruntled ex-employee of Mount Vernon to break into and attempt to steal Washington's skull. (He ended up with the skull of a different Washington relative.) After the theft, a new tomb was finally constructed, and Washington got his wish to be interred there.

Samuel Adams

Founding Father Samuel Adams signed one more founding document that even his second cousin John Adams, putting his name on all but the Constitution. He also served as governor of Massachusetts, per the Encyclopedia Britannica, and ran for various other offices.

By the time he reached his 80s, Adams knew his time was limited. According to "Sam Adams: The Father of American Independence," he was failing physically but was still there mentally, so when he got his family together and told them very specifically that he did not want a big funeral and insisted on a plain coffin, they would have known he meant it. But once he died on October 2, 1803, his wishes went out the window.

Ideas thrown around for Adams' funeral included a procession accompanying the coffin, perhaps made up of schoolchildren or survivors of the Battle of Lexington. In the end, the funeral was even bigger than that, with one friend of the Founding Father saying it turned into "the usual parade" to Boston's Granary Burial Ground. There was a large procession, but it included a bunch of politicians. Perhaps feeling guilty they ignored what he wanted, his loved ones did end up burying him in a simple coffin ... which lots of other people got mad about. In fact, 54 years later, it was still such a sticking point for his admirers that they dug him up and put him in a much nicer coffin before reinterring his body.

John Hancock

Imagine living your whole life and doing some seriously amazing thing, knowing that your name will go down in history as a risk-taker and a patriot. And then it turns out everyone knows just you as slang for a signature, since one time you wrote your name really big. (And, secondarily, as a life insurance company.)

John Hancock got to sign his name so large on the Declaration of Independence because, as the Encyclopedia Britannica notes, at the time, he was the president of the Continental Congress. He would later go on to serve as the governor of Massachusetts. However, he also missed out on some big gigs, including the command of the Continental Army to George Washington, and, according to "John Hancock," the position of the first U.S. vice president to John Adams.

Towards the end of his life, Hancock suffered from gout so bad that he had to be carried places. But "Dorothy Quincy, Wife of John Hancock: With Events of Her Time" records that his death still came as a shock to his loved ones. He died October 8, 1793, aged 55. Hancock left instructions for a simple funeral, although this didn't happen. Thousands of people came to pay their respects before he was buried. The day of his funeral, which was covered in great detail in pamphlets and newspapers of the time, the church bells in Boston tolled for an hour straight. Hancock was buried at the Granary Burying Ground in that city, with many other famous patriots.

Patrick Henry

If you know one thing about Patrick Henry, it's probably that he said, "Give me liberty or give me death!" You might not know when he said it or why, but he's definitely that guy.

It wasn't the only impressive thing he said in his time, though. In fact, the Historical Marker Database reports Henry was "the most famous orator of his day." (His most famous quote, for the record, was part of a speech he gave at the Second Virginia Convention, in front of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, among others.) His silver tongue helped him become a successful lawyer, and he also served as governor of Virginia. Henry's issues with the U.S. Constitution led to the inclusion of the Bill of Rights. Towards the end of his life, Henry was offered some major positions but kept turning them down, including a seat in the Senate, the chief justiceship of the Supreme Court, and ambassador to France. He might not have had time for anything so time-consuming, considering he fathered a whopping 17 children.

Patrick Henry died on June 6, 1799, aged 63, according to The Orlando Sentinel, and was buried on the estate he'd purchased only five years before, at Red Hill, Virginia. It's a small family graveyard, and his second wife is buried next to him. Henry's loved ones obviously knew his name would go down in history, as his gravestone is etched with the simple but extremely grand pronouncement "His fame his best epitaph."

Roger Sherman

The name Roger Sherman might not ring any bells, and there's a good chance he was never mentioned in your school history classes. Still, he was part of the larger group of Founding Fathers, and he has one major claim to fame that not even the Big Seven can top: Sherman was the only person to sign all four of the "founding documents."

According to the diary of his friend and colleague Ezra Stiles (via "The Life of Roger Sherman"), the Founding Father was a "genius" when it came to politics and the law, and he "filled every office with propriety, ability and though not with showy brilliancy, yet with that dignity which arises from doing everything perfectly right." Besides signing all the most important documents in early U.S. history, the U.S. Senate's official website records Sherman was instrumental in coming up with "The Great Compromise," which invented the idea of two houses in Congress, where one was proportional representation based on a state's population, and, in the other, all states had the same number (two). This made both big and little states happy, or at least content. Sherman went on to serve in both houses of Congress and was the treasurer of Yale.

He died on July 23, 1793, aged 72, and was buried at the Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut. Unlike Thomas Jefferson's short and sweet one, Sherman's epitaph tries to fit in seemingly all his achievements and runs to almost 200 words.