Was This The First Banned Book In The U.S.?

More than 270 books were challenged or banned in 2020, and the numbers are rising, said Banned Books Week. "We're seeing an unprecedented volume of challenges in the fall of 2021," said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association (ALA) Office for Intellectual Freedom in an ALA press release. "In my 20 years with ALA, I can't recall a time when we had multiple challenges coming in on a daily basis."

Some of the most consistently banned books are George Orwell's "1984," Mark Twain's "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," Harper Lee's "To Kill a Mockingbird," and Maya Angelou's "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings," said Playground Equipment. Despite the attempted censorship, many of the challenged books still stay popular. Case in point: J.D. Salinger's "The Catcher in the Rye" has been called the most censored book in the United States, but the American School Board Journal also noted that high schools chose it as their second-most taught novel, quoted Stephen J. Whitfield in "Cherished and Cursed: Toward a Social History of The Catcher in the Rye."

Book banning in America goes back to before the United States existed — to the times of the Puritans. Just like contemporary conservative-minded people, the Puritans believed certain behaviors, thoughts and concepts were considered unseemly and inappropriate for public dissemination, said Atlas Obscura.

How a maypole antagonized the Puritans

The Puritans never liked businessman John Morton, who came to Massachusetts in 1624 to start a new life. "He was very much a dandy and a playboy," explained William Heath, a retired professor from Mount Saint Mary's University, to Atlas Obscura. Within a few years, Morton captured so much ire for his antics that the Puritans exiled him. Morton found trouble when he created his own community within the Plymouth Colony. His settlement, known as Ma-Re Mount (or Merrymount) envisioned a utopian lifestyle, one that included Native Americans. It wasn't just the commerce that the new colony took away that bothered the Puritans, but how the group lived their unorthodox life. Especially appalling was how Merrymount encouraged dancing, an activity that was banned in general, and made worse by including Native Americans in their celebrations. Plymouth's governor William Bradford gave Morton the nickname "Lord of Misrule."

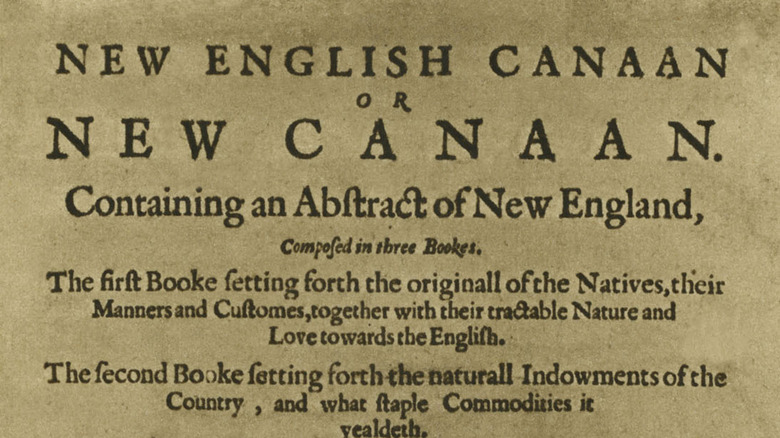

The final violation became the 1628 May Day festival where Morton's 80-foot maypole overtook the village's sky as the rabble-rouser encouraged everyone to dance and drink around it. The Puritans felt compelled to address the travesty with a militia led by Myles Standish, which cut the pole down and stopped the event. As punishment, Morton went to trial for selling the Natives arms and was exiled to an island off New Hampshire. But Morton got back to England and sued the Massachusetts Bay Company — a trial that led to a book deal and a tome the Puritans hated, "New English Canaan."

A banned book ... and Morton moves to Maine

Morton's 1637 book, "New English Canaan," tore into the Puritan lifestyle, said Mental Floss. The Puritans, already incensed by Morton's hedonistic ways, found the book blasphemous and banned it. Morton also found inspiration from mocking local leaders, such as the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Endecott, who was referred to in the book as "Captaine Littleworth," and Miles Standish, who was dubbed "Captaine Shrimp." Plymouth's governor William Bradford proclaimed Morton's effort as "an infamous and scurrilous book against many God and chief men of the country, full of lies and slanders and fraught with profane calumnies against their names and persons and the ways of God," said Atlas Obscura.

Morton tried to return to Massachusetts, but was not allowed back into the area. He ended up dying in Maine in 1643. Later, the Puritans would also challenge other books that didn't align with their principles, such as John Eliot's "The Christian Commonwealth" in the 1640s and William Pynchon's "The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption" in the 1650s. The authors of the first books banned in American got off relatively easy, according to Mental Floss. From 259 to 210 B.C. the Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang took a proactive stance with book banning. He prevented any disagreeable publications from occurring by burying 460 Confucian scholars alive. Appalling, but effective.