What Happened To Dorothea Puente's Victim Everson Gillmouth?

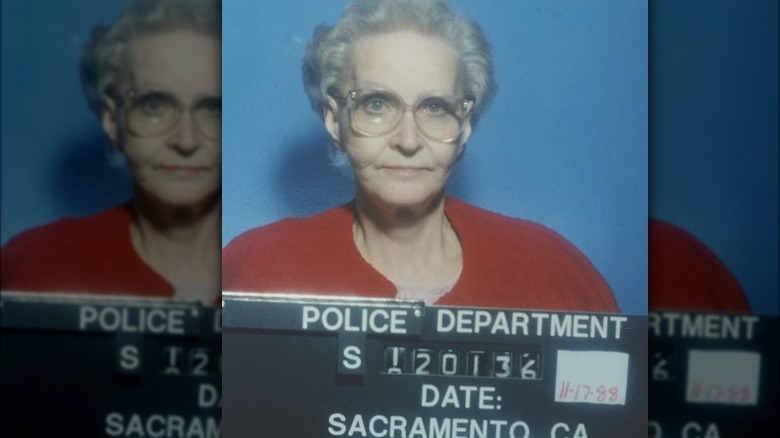

Dorothea Puente is one of the last people any would suspect was a serial killer. She ran a boarding house (pictured above) that catered to those in need and fit the image of a prototypical grandmother, with white hair and oversized glasses. However, her alleged body count — which could be as high as nine victims — speaks for itself.

According to ABC 10, Puente's typical modus operandi involved drugging her victims, who were usually elderly or disabled tenants in her boarding house, then hiding their bodies. Most of her victims were found in her backyard.

One of Puente's earliest victims was a man named Everson Gillmouth. Gillmouth's murder differed in a few ways from Puente's other crimes, and he was a victim that she pursued for quite some time before killing him, a pursuit that started while she was in prison and ended with a wooden box dumped on a riverbank (via Crime Museum).

Dorothea Puente's early life

True crime buffs will no doubt be aware that serial killers often have troubled childhoods and difficult lives. Of course, there are exceptions, but it's a trend too common to ignore. Dorothea Puente, born Dorothea Helen Gray, fit the trend (via Sactown Magazine).

Puente was born in 1929, part of a large family — she was the sixth of seven children — that could be described in many ways, but "stable" isn't one of them. Her father died from a bout with tuberculosis when she was just 8 years old, and that left her in the care of her alcoholic mother. Ultimately, Puente's mother lost custody of her in 1938, and not long after she was killed in a motorcycle crash. This meant that Puente lived with relatives until she was 16 years old, at which point she struck out on her own and moved to Olympia, Washington, where she made her way as a sex worker.

What followed were years of rocky marriages and disinterest in parenting that mirrored her mother's attitude toward her. She reportedly had two daughters with her first husband, and one of them was sent to live with relatives while the other was put up for adoption. Puente also had run-ins with the law as early as the 1950s, when she was caught trying to pass checks under a fake name. That earned her a four-month jail stint.

Puente the lying landlady

In interviews conducted by Sactown Magazine while she was still in prison, before her death in 2011, Puente seemed to have possibly been a habitual liar, which, in fairness, is a useful skill for a serial murderer hoping to remain undetected.

She told stories of dancing for the Radio City Rockettes, something the dance troupe's own records contradict, and spun yarns about hob-nobbing with Hollywood royalty like Rita Hayworth and politicians like John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan. She even claimed that her fourth husband, Axel Johansson, was the brother of heavyweight boxer Ingemar Johansson, even though the latter's obituary lists his only surviving brother as a man named Rolf, despite Axel being verifiably alive at the time.

This skill set helped her keep up appearances when she opened her first boarding house in the 1970s. She quickly gained a good reputation with social workers in search of suitable places to house their clients. This solid reputation would be a major benefit in Puente's future murderous endeavors.

In the early '80s, she opened her doors to her good friend Ruth Monroe. Monroe's husband was terminally ill, and she moved in with Puente for support. But just weeks later she was found dead, having overdosed on codeine and Tylenol (via Crime Museum). Dorothea denied involvement, arguing that Monroe had been in a deep depression. The death was ruled a suicide.

Dorothea Puente lands behind bars ... again

Thirty years after Puente spent four months in jail for trying to pass bum checks, she wound up in the clink again. Only this time, it was on substantially more nefarious charges.

According to Crime Museum, just weeks after skirting suspicion in Ruth Monroe's death, a 74-year-old man named Malcolm Mackenzie alleged that Puente had drugged him, then stole his pension. Given the benefit of hindsight, it seems that this was an early, non-lethal version of the crimes Puente would become infamous for.

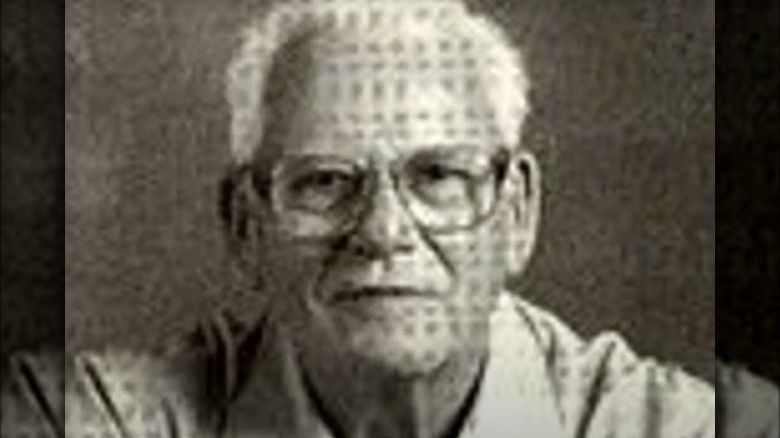

While serving time for this crime, Puente started to exchange letters with Everson Gillmouth (above). The two developed a relationship. According to The U.S. Sun, Gillmouth was a 77-year-old retiree. Upon Puente's release in 1985, the two moved in with each other and opened a joint bank account. Not long after, Gillmouth disappeared.

According to the Los Angeles Review of Books, Puente's habitual-lying was in full effect in a letter she sent in late 1985, shortly after Gillmouth vanished. "Everson and I got married early Dec. We are quite happy. We will stay here with his longtime friend until Dec 29th, then go to my family in Tulsa," it read. "I have three grown children. Hope this finds you well. Everson will write after we get settled." Almost every word of this was untrue, including where Puente had signed her name as Irene.

What's in the box?

After Gillmouth's disappearance, Puente hired a handyman, Ismael Florez, to do some work on her house. According to Crime Museum, Florenz was tasked with installing wood paneling. For his troubles, Puente gave Florez a bonus and a truck. Specifically, a red 1980 Ford pickup truck, just like the one Everson Gillmouth used to drive.

Florez later received an additional, unusual request. Puente wanted him to build her a wooden box that measured six feet long by three feet wide, claiming to need it to hold "books and other items." Florez then allegedly helped Puente leave the box by a river.

On January 1, 1986, some fisherman found the box and made a grisly discovery upon opening it. Inside was the body of an elderly man. It was Everson Gillmouth, but it would be three more years before he was identified. In the meantime, Puente continued to forge Gillmouth's name on letters to his family and collected his pension checks.

Dorothea Puente the killer is revealed

Dorothea Puente's downfall came when a social worker who had placed a client — Alvaro "Bert" Montoya — in Puente's boardinghouse, realized she hadn't heard from him. Puente gave conflicting explanations for his absence (via Sactown Magazine), which raised the social worker's suspicion and she called the police. Eventually, police searched Puente's backyard, where they discovered seven bodies. All of them had been boarding house residents. TV cameras captured Puente watching from a boardinghouse window as investigators pulled corpses out of the ground.

Ahead of her trial, a psychiatrist diagnosed Puente with antisocial personality disorder, one of the hallmarks of which is a tendency to manipulate others. Puente's trial lasted for months and featured dozens of witnesses and a mountain of evidence. Ultimately, she was convicted on three charges — two counts of first-degree murder and one count of second-degree murder — which dealt her multiple life sentences. She maintained her innocence until her death in prison in 2011 (via Crime Museum).