The Most Powerful Indigenous Tribes In History

For many people, the phrase "indigenous tribes" might conjure up images of hunter-gatherers living traditional lifestyles on the fringes of modern societies in Africa and South America. This image, of course, relies on the UN definition of what constitutes an "indigenous tribe." But then again, what does tribe even mean?

Originally, according to Etymology Online, the word described political divisions within the Roman Republic. A more modern English definition, per Merriam-Webster, describes a tribe as "a social group composed chiefly of numerous families, clans, or generations [with] a shared ancestry and language." Using these two definitions, suddenly it is possible to include many more groups from all over the world.

As it turns out, despite the connotation of the word "tribe," many of history's most powerful entities were born of tribal confederations that were often considered barbarians on the fringes of the civilized world. Modern ethnolinguistic groups such as the Lithuanians, Asturians, Basques, and Mongols, all arose through this ethnogenesis. As they formed larger states, they eventually ditched tribal organization in favor of other forms of government. Here are some of the world's most powerful tribes and the men and women that made them great.

The Mexica

The Mexica tribe (a.k.a. the Aztecs), was not indigenous to Mexico. According to archeologist Nicoletta Maestri (via ThoughtCo), the Mexica migrated from the mythical island of Aztlan along with six fellow Nahuatl-speaking tribes. According to Deseret News, Aztlan was probably located in the Rocky Mountains, perhaps Utah. Most of Nahuatl's Uto-Aztecan relatives (e.g. Hopi, Ute, Comanche, and Shoshoni) are spoken in the Western U.S.

According to Mexico's INAH, the Mexica left Aztlan on orders from the sun god Huitzilopochtli on a journey that in Spanish translates as "the pilgrimage." The legend says that upon seeing an eagle perched on a cactus, the migrants stopped. There, on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, they built a city called Tenochtitlan (modern Mexico City) as their capital.

The Mexica soon imposed themselves in their new homeland. According to the "Essential Codex Mendoza," a string of Mexica rulers expanded the state as far as Central America and created the Aztec Empire. As Spanish conquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo noted in his memoirs, this empire was extremely rich, its capital more populous than many European cities, and unmatched in its military might. But it fell as swiftly as it had risen in the face of Old World disease and technology. Although the Mexica were assimilated into New Spain, their Nahuatl language survives as does their name, preserved in the modern country of Mexico.

The Amhara

The Amhara are not a single tribe per se, but an ethnolinguistic group consisting of many tribes that dominate Northern and Central Ethiopia. According to Atlas of Humanity, these tribes built the core of Ethiopia with some of the best dynastic credentials and the treasure to back up their claims to fame.

The Amhara people dominated the Ethiopian elite, per Britannica, providing the country with all of its rulers except one from 1270 onward. But there was another claim to fame. According to the Horniman Museum, Ethiopia's ruling dynasty traced its lineage from Israel's King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, who gave birth to their son Menelik. Solomon eventually sent Menelik to establish the worship of the one, true God in Ethiopia and he became the scion of the Solomonic Dynasty. As Atlas of Humanity notes, the Amhara's ancestors in part came from Sheba (Sabaa) in Yemen, so there may be truth to this story.

As if the blood of Solomon wasn't enough, the Amhara rulers had another treasure to boost their Israelite pedigrees. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the Ark of the Covenant ended up in Ethiopia in the 6th century BC, where it is claimed to still be today, in Axum's Church of Our Lady of Mt. Zion. Thus, these Amhara Christian rulers, with the blood of Israel's legendary kings running through their veins and in possession of the most valuable artifact in the Abrahamic world, could claim a spiritual authority that made them a truly unique and one might say – legendary – group of people.

The Lithuanians

The pagan Lithuanian tribes had already been coalescing in the early 13th century to resist German crusader encroachment, who, according to The Conversation, had subjugated coastal Latvia and Estonia. According to Kristina Markman of UCLA, a group of Lithuanian nobles signed a 1219 treaty with Galicia-Volhynia, suggesting that a unified state was quickly forming. By 1253, according to LRT, the Lithuanian duke Mindaugas embraced Catholicism, hoping that papal recognition would halt crusader attacks on his lands.

Unfortunately for Lithuania, Mindaugas was murdered in 1263 and his country reverted to paganism. But Lithuania's power did not wane. In fact, according to Russia Beyond, the pagan grand dukes of Lithuania only grew stronger, adding Ukraine and Belarus to their domains in the 14th century. Lithuania's strength attracted potential allies – if only its rulers could be converted to Catholicism.

In 1386, according to Columbia University, Poland was seeking a husband for its "king" Jadwiga, while the Lithuanian duke Jogaila needed a wife. The Polish nobility matched them under the Union of Krewo, and Jogaila and Lithuania became Catholic. The marriage gave Jogaila (now Władysław II Jagiełło) a united Polish-Lithuanian army to crush the German Teutonic Order, which was intruding on Lithuanian lands from its Baltic domains. At the 1410 Battle of Tannenberg, the Polish-Lithuanian army crushed the crusaders, making Poland-Lithuania the foremost power in the region. Eventually, the two countries united into the Commonwealth, a superstate that dominated Renaissance Eastern Europe and saw the flowering of Polish art, literature, and science. Pretty good for its humble pagan origins.

The Lamtuna Berbers

According to "Studies in West African Islamic History," itinerant preacher Abdullah ibn Yasin and his zealous "al-Murabitun" (Almoravid) followers won over the Lamtuna Berbers to their austere, militant Islamic creed. The Lamtuna became the core of the Almoravid religious movement that formed the basis for a new emirate in Morocco. By 1080, as Britannica notes, the Lamtuna and their confederates had conquered much of North Africa to form the Almoravid Emirate.

While the Almoravid Emirate expanded, Muslim Iberia was receding in the face of southward Christian expansion. According to Muslim historian and chronicler Abd al-Wahid al Marrakushi (via De rei militari), Al-Andalus' taifa kingdoms were "facing annihilation" at Christian hands, surviving only through costly tribute payments. Thus, Motamid of Seville, fed up with Christian rule, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and requested the Almoravid emir Yusuf ibn Tashfin's aid.

According to the book "The Cid and his Spain" not all Muslim rulers welcomed the Almoravids. The austere desert warriors were a world away from al-Andalus, where Muslim rulers lived in luxury and wine (forbidden in Islam) flowed freely. It was unlikely that Yusuf would leave after freeing them from Castilian rule. But Motamid, not wishing to go down in history as the man that "surrendered al-Andalus to the infidels" accepted the risk. According to al-Marrukshi, Yusuf's intervention saved Iberian Islam. At Sagrajas in 1086, Almoravid forces routed their Castilian counterparts and consolidated their grip on al-Andalus. The Catholic kingdoms would have to wait another century to conquer al-Andalus.

The Astures

According to Perseus Digital Library, the name "Astures" refers to tribal groups that lived in the mountains of Northern Iberia. Although they came under Roman rule, these fiercely-independent mountaineers survived to fight another day. In the 8th century, they planted the first seeds of the country today known as Spain.

When Tariq ibn Ziyad conquered the Visigothic Kingdom of Iberia for Islam, he overcame heavily fortified cities and a powerful Visigoth army. By the time he reached northern Iberia, the hardest part of the conquest seemed behind him. According to the Chronicle of Alfonso III, Tariq left a governor named Munuza to administer Asturias, Cantabria, and their fractious tribes, believing the region incapable of meaningfully resisting.

Tariq and Munuza, however, could not have been more wrong. As recorded in the Chronicle of Alfonso III, a Visigoth noble and warlord named Don Pelayo (above) recruited a handful of warriors from among the Astures and rose up against Muslim rule. In 718 (or 722), this force defeated the Muslims at Covadonga. According to the Cronica Albeldense, the Astures proclaimed Pelayo their king, establishing a bulwark against Islamic expansion that kept Iberian Christianity alive and eventually pushed the conquerors out of the peninsula. The Astures gradually disappeared as tribal boundaries dissolved, but their legacy lives on in the Spanish saying: "Asturias is Spain, the rest is reconquered land."

The Comanche

According to Texas Public Radio, the movie "The Searchers" is based on the true story of the search for 9-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker, who was kidnapped during a Comanche raid on the Texas frontier. The hatred between the Comanches and American settlers is highlighted when Texas Ranger Patrick Wayne shoots a dead Comanche's eyes out to deny him an afterlife.

Wayne's action illustrates a historical enmity between the Comanche and American settlers. The Comanche were one of the Great Plains' most powerful tribes, feared and respected for their horsemanship, ferocity, and willingness to resist American encroachment. One particular tribe, which Spanish chronicles, per NPR, referred to as the Quahadis, resisted the U.S. government to the bitter end. They refused negotiation or trade with Americans, Mexicans, other Europeans, or even other tribes, preferring to raid them instead.

In 1871, an alliance of Americans and Tonkawa natives decided to end the Quahadis once and for all. Chief Quanah Parker (above), son of a Comanche chief and captive Cynthia Ann Parker, was ready for them. As the American cavalry set out, the Comanches engineered panic among their horses while the men were at rest, capturing 70 of them in the confusion. According to the Texas Historical Commission, the U.S. Army turned to attrition, driving the Comanche away from their food sources and killing the horses and buffalo they depended on. In 1875, Parker and his holdouts accepted reservation land in Indian Territory and the Comanche resistance ended. Altogether, the Comanche had held out over 40 years.

The Romans

According to the University of Chicago, the Etruscan king of Rome Servius Tullius divided the people of Rome into 30 (later 35) tribes that were arranged topographically. These units eventually formed the basis for the Roman Republic's voting system, helping elect the officials that turned Rome into a Mediterranean empire.

The voting tribes of Rome had a plethora of functions, most importantly levying soldiers for the army and collecting taxes/tributes from their members. But tribes also had the right to elect officials. According to the Roman Constitution, the Comitia Tributa met to elect the lower magistrates, while the common (a.k.a. plebeian) members of the tribes met separately to elect their own representatives independent of Rome's wealthy patrician families. But as tribes tend to do, they opposed and fought each other for power.

Political affiliation today has become a group identity for many. Such was the case even in the Roman Republic 2,000+ years ago. According to Livy's History of Rome, a tribune named Marcus Flavius called for the rebel Tusculani people to be severely punished for their disloyalty. All the tribes but one – the Pollia – vetoed his proposition. The Tusculani eventually joined the Roman Papiri tribe, bringing their grudges against the Pollia with them. Thus, as Livy notes, the political climate between the two tribes became one of outright hostility, as no member of either tribe ever voted for a candidate of the other for centuries after. Regardless of the story's veracity, the Bryn Mawr Classical Review notes that such friction did occur, making the tribes early versions of modern political parties.

The Qiniq

The Qiniq were an Oghuz-speaking Turkic tribe from Central Asia to whom Turkey owes its very existence. According to "The Turkic Languages," the pagan Turkic-speaking tribes of the Early Middle Ages began converting to Islam as mercenaries in Arab and Persian armies. Among these was a man named Seljuk, a Qiniq refugee whose clan enemies had forced him out of his home. Eventually, Seljuk and his descendants united the Oghuz tribes under the Qiniq and forged an empire that encompassed Persia and much of the Arab world all the way to the Mediterranean.

Seljuk's descendant, Sultan Alp Arslan (above), brought these Turks to the pinnacle of their power with a victory over the Byzantine Empire at Manzikert in 1071. According to Medievalists, the Seljuk victory had several important consequences. First, the Byzantine emperor, Romanos Diogenes, was captured alive. His captivity set off a power struggle among his rivals in Constantinople, who deposed him, while his mercenary commanders attempted to create their own fiefdoms out of Anatolian Byzantine territory. The Turkic-speaking tribes of the Seljuk Empire also took advantage of the instability to settle permanently in Anatolia, beginning the Turkification of Anatolia at the expense of the then-dominant Greek language and Christian faith. Had Alp Arslan not won this important victory, Turkey might look like a very different place today, and no one would have remembered the Qiniq.

The Kiyat Mongols

According to the Penn Museum, Kiyat Khan Yesugei was killed by the Mongols' Tatar enemies, leaving behind a wife and a 10-year-old son. His tribe deserted the family. The boy, however, would return to write his tribe's name into the annals of history.

Yesugei's son Temujin set about bringing together a retinue of warriors to take back his rightful place as leader of the Kiyat clan, and eventually, of the entire Borjigin tribe. But controlling his tribe was not enough. He wanted more. Eventually, he united the tribes of the Mongolian steppe and embarked on a campaign of conquest across Asia, subjugating Iran, China, and parts of Russia.

So what was the key to the Mongol success? According to History, Genghis Khan, as Temujin came to be called, broke down the Mongol tribal system in favor of making these warriors loyal to him personally rather than to their clans and tribes. Thus, soldiers served together in units of 10 regardless of tribal affiliation. Whenever he conquered a new tribe, Temujin killed their leaders and forced the survivors into the Borjigin tribe fold. In eliminating clan disputes, Temujin created a force personally loyal to him, giving it the unity and cohesion needed to crush much larger and more advanced opponents such as the Chinese.

The Quraysh

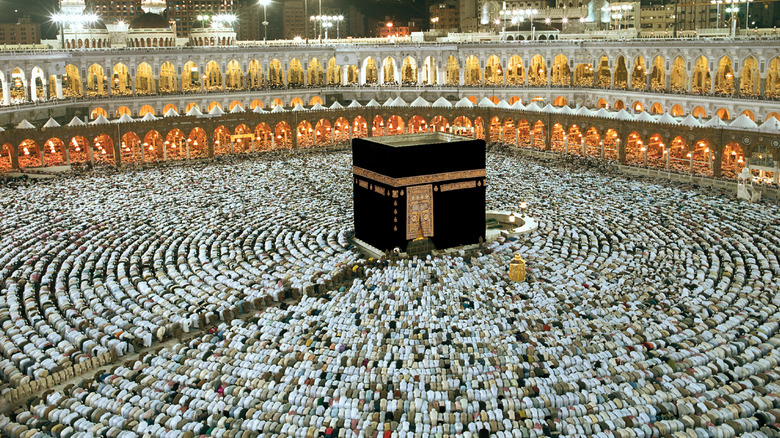

The Quraysh tribe is virtually unknown outside of Islam and the Middle East, but this tribe is one of history's most important. According to PBS, tribal identity, based on close kinship ties, was the basis of relations in pre-Islamic Arabia. The Quraysh tribe was among the most influential, thanks to its control of the city of Mecca. Even before the advent of Islam, according to the International Journal of Middle East Studies, Mecca was a commercial and religious hub that drew pilgrims to its principal shrine – the Ka'aba. The Quraysh had outmuscled their rivals for control of the town and were firmly ensconced there by 570, when the tribe's most famous member, the Islamic prophet Muhammad was born.

Muhammad belonged to the Banu Hashim clan of the Quraysh, from whom the Jordanian Royal Family today claims descent. Driven by the new faith of Islam, Muhammad and his followers united the fractious tribes of the Arabian peninsula through a mix of diplomacy and force. Following his death, Muhammad's successors, as UNESCO notes, turned their attention to conquests outside of Arabia, seizing everything from Iberia to Pakistan in a matter of decades. The Quraysh would continue to dominate the Islamic world for centuries to follow through the Umayyad and Abbasid clans, who ruled as caliphs throughout the Middle Ages. Of all the tribes on this list, the Quraysh legacy is the most enduring, as according to Pew, over 1.8 billion people follow the teachings of its most famous member.

The Nubians

The term "Nubian," per The Economist, refers to the indigenous inhabitants of Northern and Central Sudan and Southern Egypt, whose history goes as far back as pharaonic times. While Nubians today are mostly Muslim and increasingly Arabized, these tribes once created rich, thriving Christian kingdoms in medieval Sudan. According to the "Military History of Late Rome," the inhabitants of Nubia beyond the borders of Roman Egypt began to coalesce into a series of tribal confederacies in the late antique period, resulting in the Christian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia. These kingdoms adopted a system in which a high king ruled over lesser rulers, presumably rulers whose power was based on kinship ties within a tribal setting.

The most interesting facet of medieval Nubia was its Christian religion. According to Dr. Vince Bantu (via Jude 3 Project), Nubia was evangelized from Coptic Egypt, whose seat was Alexandria, and had tense relations with the Christian patriarchs of Rome and Constantinople over theological disagreements. Unlike Egypt, however, the Nubian kingdoms successfully resisted Arab invasion. In subsequent negotiations, Nubia accepted Muslim rule in Egypt in return for Muslim recognition of Nubia's Christianity. Over time, as Mustafa Musad explains in the Journal "Sudan Notes and Records," the Nubian kingdoms eventually came under Islamic rule but ancient ruins — like that of a monastery discovered at Al-Ghazali, Sudan (pictured) — remain as reminders of the area's Christian past.

The Vascones

"Vascones" is a Latin term referring to the ancient and medieval ancestors of the modern Basque people. According to the City of Pamplona, the Romans conquered the Basque homeland in the 1st century BC. Like their Astur neighbors, however, they survived to fight another day. This group of fiercely independent mountaineers eventually rose to prominence amid the border conflicts between the Frankish Carolingian Empire and Muslim Andalusia.

Ninth-century Navarra was a contested land between Charlamagne's Carolingian Franks and local rulers, and the dominant Iberian power, the Muslim Umayyads. The Vascones, per Britannica, annihilated the Frankish rearguard of Charlemagne's army at Roncesvalles in 778, but the Franks did not give up. In the subsequent free-for-all between Umayyads, Franks, and local potentates an opportunity arose for the Vascones to consolidate a kingdom of their own.

Into this mess stepped Iñigo Arista (above), a Basque Catholic warlord from Pamplona who climbed the political ladder by shrewdly playing his enemies against each other. According to the Enciclopedia de Navarra, Arista rose to power by allying with Franks, Umayyads, and local Muslim neighbors alike, changing sides when it suited him to defeat any enemy he deemed a threat to his position. Once the Umayyads expelled the Franks from Navarra, they also forced Arista into submission but allowed him to retain his position. His small principality evolved into the Basque-speaking Kingdom of Navarra. This state would sire the dynasty that unified Christian Spain – the Jimena – although it would relegate Navarra to a second-rate kingdom behind its fellow Christian states of Castille and Leon.