The Untold Truth Of Antarctic Explorer Ernest Shackleton

There aren't a whole lot of places left on planet Earth that are still unseen by human eyes, but a century ago the world was still a pretty mysterious place. From the top of Mount Everest to the remote Arctic, everyone with some capital and an adventurous spirit wanted to be the "first" somewhere, even though that usually just meant "the first European."

In those days, traveling a few miles into town to buy sugar and bacon could be an ordeal — now imagine trying to organize a couple of dozen guys for a months-long voyage to the coldest place in the world. Ernest Shackleton never made it to the South Pole, but his expedition was no less impressive just because it didn't succeed. In fact, given what is now known about the Antarctic, if you measure success in terms of lives not lost, Shackleton's voyage was one of the most successful of his time. In case you are a bit shaky on the details, here's the recap — the expedition arrived in Antarctica, the ship got locked up in the ice, the ship sank, the men made it to Elephant Island, and Shackleton himself embarked on a daring mission to find civilization and help for his stranded crew.

Since the remains of Shackleton's ship the Endurance were discovered at the bottom of the Weddell Sea in March 2022, it's worth taking another look at some of the untold truths of Ernest Shackleton and his legacy.

Shackleton's father wanted him to be a doctor

Ernest Shackleton was born in Ireland in 1874. His dad was a doctor, and like so many other doctor dads, Shackleton the elder had certain expectations for his son, among which was the one where he was supposed to follow in his father's footsteps. In pursuit of this dream that wasn't really his own, the family moved to London where they hoped their son would learn all about cathartics, opium, wraps, gargles, and whatever else doctors recommended to sick patients in the late 1800s (at least they were mostly past "bleeding" as an acceptable remedy).

Anyway, according to the BBC, Shackleton didn't find any of those things especially interesting. At the age of 13, his parents enrolled him in Dulwich College, where he sort of just languished, not because he wasn't smart but because he was bored by the medical subjects he'd been signed up for (via "Ernest Shackleton: Gripped by the Antarctic"). Instead of reading anatomy books, Shackleton spent his time reading about ships and seafaring. By 1890, his father had finally resigned himself to the fact that Shackleton the younger wasn't ever going to be an M.D., and helped his son secure a place onboard a ship called the Hoghton Tower.

He had health problems from a young age

As a young man, Ernest Shackleton didn't just want to sail the seas, he wanted to be an explorer. Now, being an explorer doesn't necessarily mean you need to travel to dangerous, unwelcoming destinations. You could dream of exploring Hawaii or Tahiti or, you know, a place that at least has a lovely climate. But no, Ernest Shackleton wanted to freeze to death at the bottom of the world. Whatever floats your three-masted barquentine.

Shackleton left on what was supposed to be his first voyage to Antarctica in 1901 as a member of the Discovery Expedition, but he had to leave halfway through the trip. According to SouthPole.com, he developed a cough shortly after enduring two days confined to a tent while a blizzard raged outside, and a few weeks later appeared to be showing signs of scurvy. His health declined enough that the expedition leader eventually decided to send him home on a supply ship.

The authors of 2021 research published in the Journal of Medical Biography, however, aren't so sure Shackleton's only problem was scurvy. They think it's more likely he suffered from thiamine deficiency with cardiomyopathy (a chronic condition of the heart), which was probably made worse by scurvy. Ultimately, it all came down to the fact that he (like so many other seafarers of the time) hardly ate any fresh foods. Remember this, kids, the next time you're on your third day of boxed mac n' cheese.

A lot of people wanted to freeze to death in Antarctica

Ernest Shackleton was unfazed by his bad luck on that first Antarctic expedition; in fact, it seemed to make him even more determined. By 1914 he was planning his next trip to the frozen south, and just in case you were thinking that no one else in their right mind would want to voluntarily sail to Antarctica on a wooden boat, well, you're quite wrong.

According to Shackleton, the expedition needed fewer than 50 men yet received a whopping 5,000 applications. In those days, there was no such thing as a resume parser (which by the way is The Actual Devil), so Shackleton sorted them into piles labeled "Mad," "Hopeless," and "Possible" (it's not super clear what the difference was between "Mad" and "Hopeless," since the only applications he considered were the ones in the "Possible" pile).

Shackleton's review process was neither careful nor especially fair, in that he didn't really pay any attention to an applicant's qualifications, he kind of just made choices based on his gut. Which, when you think about it, is kind of similar to resume parsing since it's really just a way for the hiring manager to avoid having to read thousands of resumes and make a decision based on thoughtful consideration. Some things never change.

Shackleton had some weird hiring requirements

After parsing their resumes, Ernest Shackleton invited candidates to his office in London for a formal review. It wasn't exactly a job interview or anything, though, in fact, applicants didn't have to fill out a form or answer a ton of questions. According to Shackleton.com, the explorer didn't even ask candidates about their qualifications. Instead, he would just kind of look them up and down and ask a few arbitrary questions. For example, one candidate was chosen based on the fact that he "looked funny." Maybe Shackleton wanted someone who could lighten the mood while everyone was freezing to death in their tents? Another candidate was asked if he had good teeth and could sing. So clearly, keeping the men entertained during the long voyage was higher on Shackleton's list of priorities than having scientific credentials, sailing experience, and the chops necessary to survive life on the ice.

Interestingly, science wasn't really something Shackleton appeared to be concerned with — his interest in exploring seemed to be more about just getting there first than learning something along the way. Sure, there were scientists on board (science was pretty important for public relations), it's just that Shackleton himself didn't really care much about it. A fellow explorer once got this advice from Ernest Shackleton: "Don't saddle yourself with too much scientific work. You must decide whether you want to be a scientist or a successful leader of expeditions. It is not possible to do both."

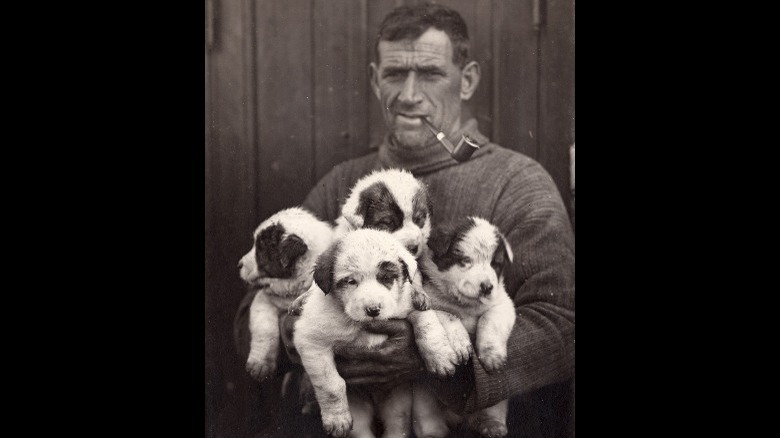

There were lots of dogs on board

Snowmobiles were definitely not a thing back in Ernest Shackleton's day, so the expedition had to have a low-tech way of moving gear around while they were trying to get to the South Pole. Dogs are about as low-tech as it gets, so Shackleton brought along 69 of them. This means dogs actually outnumbered people by a factor of more than two to one (History says there were 27 men on board, 28 if you count the stowaway who was mercifully named ship's steward, you know, vs. being thrown overboard or left in the nearest flock of penguins).

Shackleton wasn't particular about what kinds of dogs he took on board. You might have pictured huskies or malamutes but according to The Guardian, most of the dogs were mixed breed. They did have to be big dogs, though — each one weighed at least 100 lbs, presumably because big dogs can pull more weight. Each member of the crew was assigned to care for a specific dog or dogs, and some of their names are even remembered (Steamer, Wallaby, and Shakespeare are just a few).

The dogs didn't survive the journey

Dogs are pretty happy to go wherever people go, and even though life in the Antarctic was hard, Ernest Shackleton's dogs seem to have been loved and well-cared for. Of course, no one thought the ship would get locked up in ice and the crew would have to spend the winter camped out on the floes.

Things were okay at first — according to the Canterbury Museum, the men made "dogloos" for their dogs to live in and each dog was fed and cared for as the winter closed in. As history knows from accounts of travelers stranded in the snow and ice, though, food gets pretty scarce during those very cold winters, and the sinking of the Endurance 10 months later changed everything. The crew was able to salvage food from the ship before it sank, but they had to kill some of the younger dogs who were too small to really be much use to the expedition (via History).

After that, the food started to run out. Crewmen's journals noted occasionally catching a seal or some penguins (via Dartmouth), but it wasn't enough to keep everyone fed. For the dogs, scarcity turned them into a liability. There wasn't enough food for everyone, so the dogs had to be shot, slaughtered, and eaten. "It was the worst job that we had had throughout the Expedition," Shackleton later wrote. "We felt their loss keenly."

The men didn't set foot on land for 497 days

Today, the Antarctic ice is breaking apart and falling into the ocean with alarming regularity. As glaciers disappear, previously unknown bits of solid land are appearing (via Nature). In Ernest Shackleton's day, melting ice wasn't quite as dramatic as it is today, but it was still something they had to worry about. No one knew much about the weather in Antarctica, or what might actually happen in the spring when the temperatures started to get a little warmer. The ice pack where they were camped was drifting and was hundreds of miles from shore. They'd managed to salvage the Endurance's lifeboats, though, which at least provided some reassurance that if the ice broke apart under their feet they could be saved from drowning (via History).

After the Endurance sank, the men tried to walk to solid ground but it was too much for them to manage in the angry Antarctic winter. Instead of carrying on, they camped on the ice floe until it finally cracked under them, then they launched the lifeboats and set out towards Elephant Island. After six days in the freezing waters, they finally reached land and put their feet on solid ground for the first time in 497 days.

When they reached civilization, they were barely recognizable

Do you remember how you looked after the COVID-19 lockdown ended? Now imagine if you'd been locked down in Antarctica without Animal Crossing eating nothing but seal, penguin, and dog for a year and a half. That was pretty much the state of Ernest Shackleton and his five companions when they finally found civilization in May of 1916 (via Geographical).

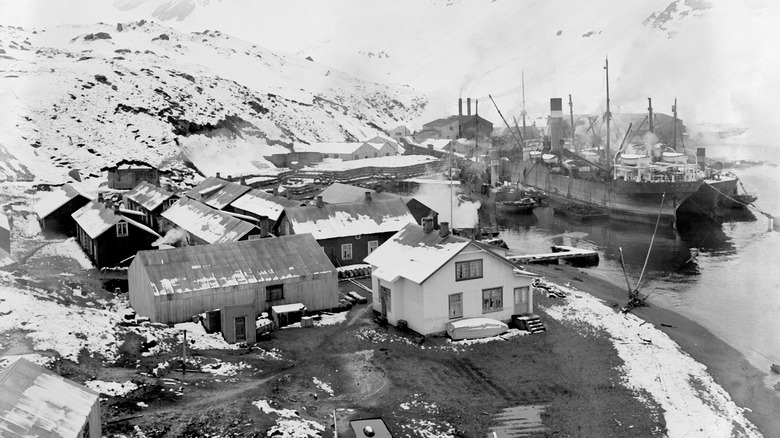

After leading his crew to Elephant Island, Shackleton and a handful of men boarded a 22-foot lifeboat and went for help. Fourteen days later they arrived in South Georgia, a tiny island southeast of the Falkland Islands in the southern Atlantic Ocean. Unfortunately, though, they landed on the wrong part of the island. According to South-Pole.com, after making landfall Shackleton and the men who were still strong enough to accompany him trekked more than 17 miles over mountains and glaciers before they finally arrived at a whaling station.

Their expedition had gained a certain amount of worldwide fame, still, no one at the station had any idea who they were on account of the long beards, matted hair, and the fact they hadn't changed clothes for months. Fortunately, the manager of the whaling station didn't send them packing the way modern managers send scruffy-looking people packing today. When he found out who they were, he took them in and helped ensure the safety of the three men who had been left on the other side of the island.

The rescue took months

Ernest Shackleton could have just gone back to England, leaving the rescue operations to someone else. He wasn't that kind of guy, though. According to South-Pole.com, Shackleton was on his way back to Elephant Island within a couple of days of his arrival at the whaling station. Shackleton and two of his men left South Georgia onboard the whaling ship Southern Sky, but even in the springtime, you can't just cruise past the poppies into the wide-open waters of Antarctica. The Southern Sky hit pack ice and, not wanting to meet a similar fate as the Endurance, was forced to turn back. The next rescue attempt was made in a Uruguayan trawler, but that ship also encountered ice and had to call off the rescue. Undeterred, Shackleton raised money to charter a schooner, but the third time was not, in fact, the charm. The schooner had engine trouble and was also unable to complete the rescue.

A lesser person might have just shrugged and presumed everyone dead, but Shackleton chartered a fourth ship — this time, it was a Chilean ship named the Yelcho. By then it was late summer, and the Yelcho had an easier time finding a path to Elephant Island. On August 30, 1916, the Yelcho arrived on Elephant Island to find all of Shackleton's men alive. Maybe not exactly well, but alive after being stranded on Elephant Island for 105 days. The expedition's death toll (not counting dogs): zero.

Ernest Shackleton enlisted in WWI

No one would have blamed Ernest Shackleton if he'd decided to retire and take up gardening or something. For a lot of people, the voyage of the Endurance would have been enough excitement for at least one lifetime, probably two.

When Shackleton and his men finally returned to England, World War I was well underway, so Shackleton did what any guy who'd just spent a year and a half eating penguin in a frozen wasteland would have done — he joined the military. His family must have been thrilled.

Shackleton became a major in the British Army, but he didn't really see any action because despite his incredible survival story he really wasn't in great physical shape. He still suffered from the same health problems that got him sent home from his first Antarctic expedition (via Smithsonian), but the army wasn't about to tell a great British hero what to go do with himself, so they gave him busy work "promoting Britain's interests" in South America. According to the Cheltenham Museum, Shackleton's wartime duties also included two weeks in northern Russia, where he was assigned to help outfit and equip troops who would be spending the winter 150 miles north of the Arctic circle.

Shackleton tried for the South Pole again

People who climb Mount Everest get "summit fever" — they keep pushing for the summit even though they're out of oxygen, suffering from altitude sickness, and walking into a blizzard. When you spend $40,000 and months of your life in pursuit of that kind of goal, sometimes death seems so much better than failure.

Ernest Shackleton suffered from something much like summit fever. Despite the horrible ordeal of his last expedition to Antarctica, he hadn't achieved his goal and the South Pole was still beckoning, so in 1921 he launched one more expedition to Antarctica. Incredibly, a few men from the previous expedition were crazy enough to join him, but they noted he didn't really seem himself (via History). Still, the 47-year-old Shackleton was in good spirits when the ship arrived on South Georgia. Because the crew had spent Christmas Day getting tossed around by a storm, Shackleton promised them they'd have a belated Christmas feast of tinned ham and plum pudding the day after their arrival. But that never happened, because Shackleton died of a heart attack in the night.

According to the South Georgia Museum, the men turned the ship around and headed back to England, where they planned to deliver Shackleton's body to his widow. But not long after their departure, they received a telegraph from Lady Shackleton, who requested her husband to be buried on South Georgia, where he had so much history.

The exploration bug ran in the Shackleton family

When you're an intrepid explorer, you're probably going to have kids who want to become intrepid explorers. After all, exploring is glamorous and sexy, and being a doctor is icky. Kids also seem woefully unable to internalize danger, and Ernest Shackleton's youngest child was certainly not deterred by his father's tales of danger and near-starvation. This could be because he was only three when his father set off on his famous voyage, so it's likely he heard a lot about the glory and not much about the mortal peril.

According to a biography of Edward Shackleton published by Royal Society Publishing, Shackleton the younger inherited his father's love of danger and exploration, and by the age of 22 he was already climbing mountains and winning recognition from prestigious organizations like the Royal Geographical Society, which gave him the Cuthbert Peek award after he returned from an expedition to the jungles of Malaysia. Evidently, he didn't want to follow too closely in Dad's footsteps, though — the leader of that expedition later wrote that Edward was interested in exploring the tropics mostly so he could "get away from being simply the son of his famous Antarctic father." And he did distinguish himself, too, pretty early on in fact. On the expedition to Sarawak (a state on the island of Borneo) he and another member of the team succeeded in climbing Mt. Mulu, the highest peak in Sarawak, previously believed to be unclimbable (by Europeans, anyway).

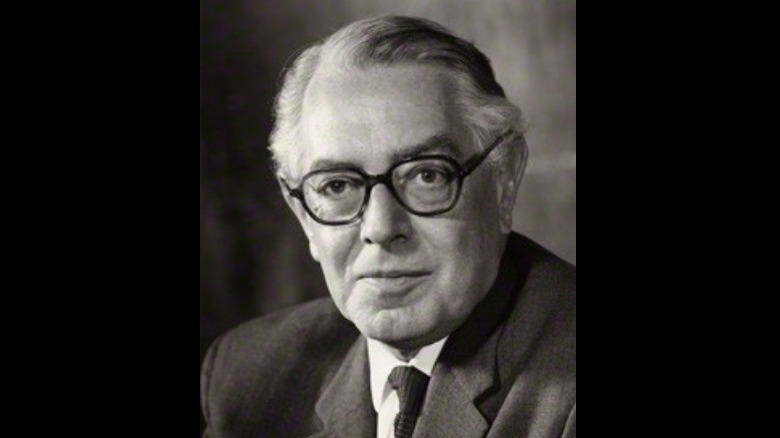

Edward Shackleton carried on his father's legacy

Some people get tired of adventure and death-defying experiences, others just move on to desk jobs so they can live vicariously through other people's adventures and death-defying experiences. Ernest Shackleton's son Edward didn't just carry on the Shackelton exploring name, he was also something of an ambassador for the occupation.

Edward Shackleton was elected president of the Royal Geographical Society in 1971. He advocated not just for exploration but for science, declaring that all expeditions should have at their heart a goal of advancing scientific knowledge. He embraced technology and by the 1980s had taken an interest in digital mapping. In fact, his interest in exploration went all the way outside of the Earth's atmosphere — in 1987, he got involved with the United Kingdom's Lords Committee on Space. Don't get too excited, though, he wasn't exactly advocating for an American-style British space program. Instead, he argued that the U.K. should focus on observing geology, soils, and human population from space, in order to further knowledge of how best to use the land.

Edward Shackleton remained committed to science and exploration almost until the day he died. In the early 1990s, failing health forced him to move into a nursing home, where he continued to make waves. He was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Sheffield in 1994. Later that same year, he died from a heart attack.

Ernest Shackleton's distant relative reached the South Pole

It's always a tragedy when someone dies before achieving a lifelong ambition. After everything Ernest Shackleton endured between the end of 1914 and the summer of 1916, he deserved to see the South Pole, but alas, it just wasn't meant to be.

For most people who die with an unfulfilled dream, that's pretty much where it ends. Shackleton, though, was lucky enough to have a family member who remembered and cared about his dream. Scott Shackleton, who ABC News says is a fifth cousin of the famous explorer, reached the South Pole on February 9, 2010. It was really more of a symbolic journey than anything else — this particular Shackleton was able to take a C-130 airplane most of the way, which may or may not have pleased Ernest after he worked so hard and failed to achieve the same goal.

"I feel so honored that I got to step on the South Pole as a Shackleton and enjoy the feeling of being there," Scott Shackleton said, though it's definitely worth pointing out that the whole visit lasted like a half hour. Still, it was an emotional moment for Scott Shackleton, who noted that "you can't really shed a tear at the pole because it freezes before it leaves your eye."