How Martha Stewart Helped Paul Newman Launch His Food Brand

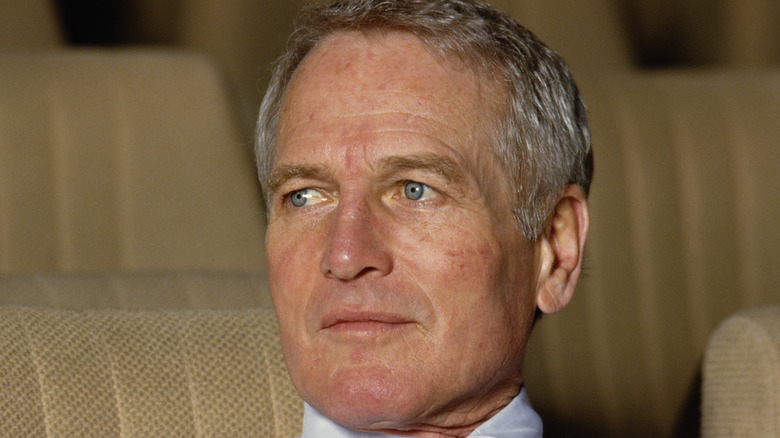

Paul Newman (above) was a guy who wore many hats throughout his life. He was an actor, a racecar driver, and an activist, but many of those hats were worn on bottles of salad dressing. Newman's face graces the labels of various items made by his food company, Newman's Own, which sells an array of products but started with the salad dressings that the brand is likely best known for.

What started as a small operation led to a massive company that donates its proceeds to charity, and according to the Newman's Own Foundation website, more than $570 million has been donated to charities around the world since Newman's Own went into business in the 1980s. Newman started his food industry endeavor with his friend, the author A. E. Hotchner. The two had an assist very early in the company's development from someone who would go on to build a brand around herself: Newman's then-neighbor, Martha Stewart (via a 2016 post by Mental Floss).

Paul Newman's salad dressing started as a Christmas gift

According to Mental Floss, the story of Newman's Own starts in late 1980. Newman was of course a massive movie star and living in Connecticut. Newman used to call Hotchner a lot and talk to him about all sorts of different things, including salad dressing. ”Oh, it was murder,” Hotchner told The New York Times in 2003. ”Just murder. Calling me constantly.'

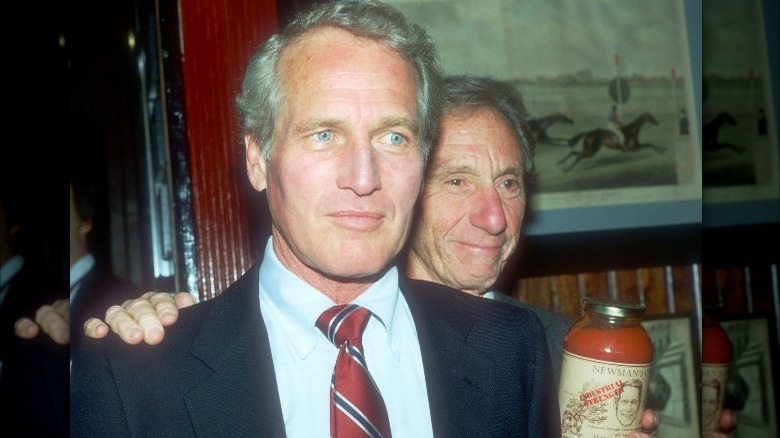

On one of these calls, Newman (pictured above with Hotchner at the launch of Newman's Own pasta sauce in 1983) asked him to come over and help him with something in his barn, and when Hotchner showed up he saw the legendary actor standing in the barn with lots of olive oil, vinegar, and other salad dressing building blocks. Newman planned to make a giant batch of dressing and pour it into old wine bottles. He then planned to give the final mixture to his neighbors as Christmas presents.

They used some creative methods to mix the first, unofficial batch of Newman's Own dressing ”We didn't have anything to stir it with,” Hotchner said. This caused Newman to run out to another barn of his near a river and return brandishing a canoe paddle. ”Newman came back and started churning, and I said: 'You're out of your ... mind. That paddle isn't sterile. Nothing is sterile.' But he didn't care. And, fortunately, after we gave it to the neighbors as gifts, no one died.”

Martha Stewart helped get Newman's Own moving

Of course, making batches of home-made salad dressing in a barn and starting a company are two drastically different things. Getting Newman's Own off the ground required some testing before going to market. According to The New York Times, Newman was told that it would cost around $400,000 to give his new dressing a proper and thorough run through the product-testing gauntlet. Newman (justifiably) found that figure insane and decided to ask his neighbor, Martha Stewart, if she would host a tasting in her kitchen.

Before she became a juggernaut of the domestic world, Stewart worked as a stockbroker until the early 1970s, but by the time Newman asked her to help with his dressing endeavor, she was working as a caterer. This skill set came in handy for gathering 20 friends and having them taste their way through a series of dressings. The tastings were blind, and the lineup consisted of Newman's dressing and a selection of other dressings that were already on the market. According to Mental Floss, Newman's Own came in first place.

The salad dressing's success launched the company's famous philanthropic endeavors

According to Mental Floss, by just 1982, Newman's Own had earned over $300,000. At that point, Newman decided that all the company's profits were to be donated to those in need, which is still the case. Each year Newman's Own takes note of its various profits and expenditures and makes sure to give away the profits by December 31.

By 1988, Newman started the first of his Hole In The Wall Gang camps. The camps — which are named after the gang in his iconic film "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" — are for children with terminal illnesses. Locations have been opened around the world.

In 2003, Newman told The New York Times that he felt the reason younger generations bought the company's products wasn't because of him, but instead the company's famous charitable endeavors. ”The younger generation doesn't buy the stuff because of me,” he said. ”They don't even know me. I think they buy it because of the charity.” Newman and Hotchner chronicled the story in their 2003 book "Shameless Exploitation in Pursuit of the Common Good."