The Secret History Of Women Bootleggers

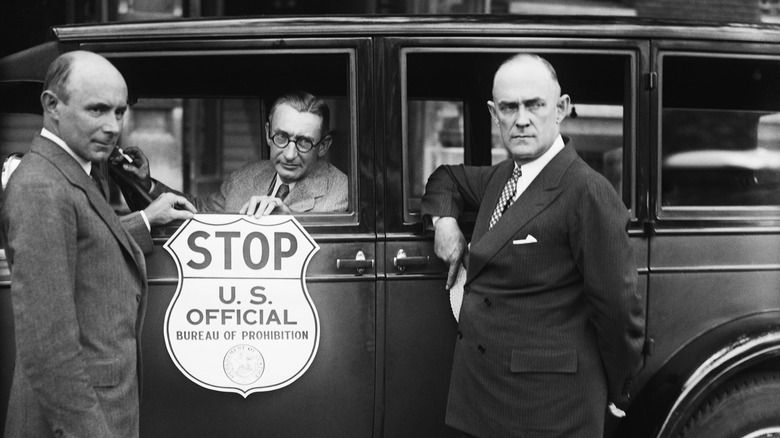

In 1920, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was passed, making alcohol illegal to produce, transport, and sell in the United States. Technically, drinking alcohol was still legal, but unless they had a vast wine cellar to stash alcohol in, it wasn't long before Americans ran dry. For people willing to break the law, this presented a unique opportunity to make money.

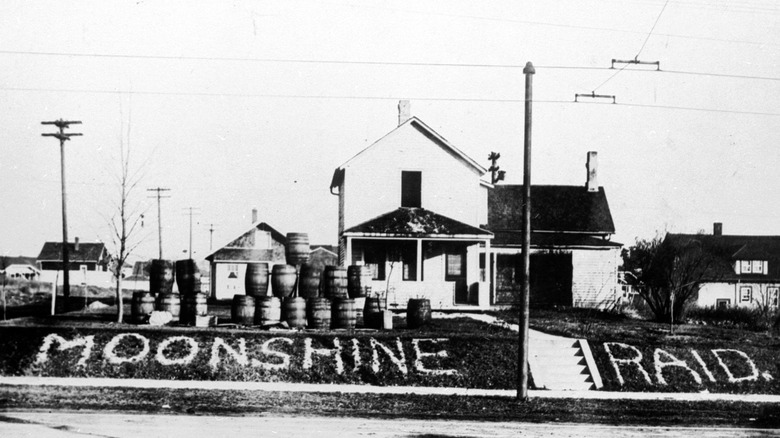

The market for "bathtub gin" and "moonshine" that ordinary citizens could make themselves skyrocketed. If high quality alcohol could be smuggled into the country, it was worth even more. As described by History, this led to a rise in organized crime and gang violence — as well as a massive amount of ordinary American citizens making, smuggling, and selling alcohol themselves. They would become known as "bootleggers."

While their role has been largely ignored in pop culture, the majority of bootleggers were women. Soon women were brewing, smuggling, and selling illegal alcohol to support their families. Some even ran their own speakeasies. The 1920s were a time of profound change for American women, and bootlegging played a role. As stated by historian Mary Murphy (quoted in Jstor Daily), "Women who made whiskey and those who patronized speakeasies were breaking both custom and the law."

There were more women bootleggers than men

During Prohibition, alcohol was illegal in the United States. It is often remembered for the rise in organized crime that occurred to supply the now-banned substance. It's not surprising that most modern Americans think of bootlegging as an activity men were at the heart of, because as described in "The Feminine Side of Bootlegging," pop culture has mostly ignored women's role in bootlegging, focusing on kingpin gangsters like Al Capone. If women are depicted at all, it is generally as flappers or "gun molls" dating gangsters. In reality, it is believed that for every man who was involved in selling illegal alcohol, there were five women bootleggers.

At the time, it was common knowledge that women were involved at every level of the illegal liquor business, from manufacturing to transport and sale. It is difficult for historians to research these women, because historical records from the time are incomplete. It is believed that the vast majority of bootleggers were never caught, so court records and newspaper headlines can only provide some insight into the true number of women bootleggers. Most sources also do not include any possible ties to organized crime, so it's unknown if the majority of women bootleggers were just manufacturing their own beer, wine, and spirits and selling them out of their homes, or if they were a part of the gangs that were gaining power and influence in the United States.

Women were (partially) responsible for Prohibition

Women were a fundamental part of every aspect of Prohibition; in fact, the calls to make alcohol illegal primarily came from women. As noted by Daniel Okrent (via Time), the dependence of many husbands and fathers on alcohol sparked the temperance movement. Tired of their husbands spending what little money the family had on alcohol and horrified by the epidemic of domestic violence that was exacerbated by alcohol, many women began to campaign for making alcohol illegal.

Many of the women at the forefront of the push for Prohibition were also campaigning for women's rights –- particularly the right to vote. Among them are famous activists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. For this reason, leaders of the liquor industry campaigned hard against women voting.

As described in "Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters: Gender and Prohibition in Butte, Montana," in some areas of the country, women actually drank more during Prohibition, but that wasn't the only reason many of Prohibition's most staunch female supporters eventually changed their mind about making alcohol illegal. As described in National Geographic, the unregulated sale of alcohol in speakeasies that regularly broke the law meant that more underaged children were served alcohol. The rise in crime was seen as more dangerous for families as well. Ultimately, just as women had pushed for Prohibition, they pushed for appeal. Both times, they got their way.

There were special terms for women bootleggers

Although the majority of bootleggers were women, they were sometimes referred to by other terms to differentiate them from male bootleggers. As described by "Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era," some newspapers at the time took referring to a female bootlegger as a "bootleggerette" or "bootleggeress." Neither of these were particularly popular and failed to make it into the public vernacular. Flappers had their own slang, including a term for a woman who was a bootlegger: "snake charmer."

The biggest gangsters of the era were called by nicknames like Al "Scarface" Capone or George "Baby Face" Nelson. While most women bootleggers were only involved with the sale of illegal alcohol as an opportunity to provide for their families, some made their fortunes bootlegging. As noted by Fred Minnick for HuffPost, some of these women became notorious, and they were given nicknames like their male counterparts. They were given names like "Moonshine Mary," "Queen of the Night Clubs," and "The Henhouse Bootlegger."

Bootlegging was many women's first crime

Some women were already in the liquor business before Prohibition. As described in Chapter Eight of "Whiskey Women," there were women running whiskey companies in Ireland, Scotland, as well as the United States — and Americans were their best buyers. While their businesses were completely legitimate before alcohol became illegal, the threat of losing massive amounts of revenue encouraged many to continue selling to the U.S. illegally.

As detailed in "The Feminine Side of Bootlegging," however, many women who had nothing to do with alcohol or crime before Prohibition also became bootleggers. Most bootleggers caught in New Orleans, for example, were in their thirties, Irish, Italian, Spanish, or Jewish, and often divorced or widowed. They often worked in shops or as laborers before Prohibition, living in working class neighborhoods. They were almost always mothers, and many couldn't resist the chance to make money as bootleggers.

Women were generally responsible for preparing meals in the home, so some already had experience with home-brewing. By becoming full-time bootleggers, these women were able to make more money than ever before without having to leave their children at home alone or pay someone else to watch them. While there was a risk of being caught, for many, it was worth the risk.

Prohibition allowed women to drink

Prior to Prohibition, the majority of drinking was done in bars by men; saloons generally only served male customers. In big cities like Chicago or New York, some women and girls had the opportunity to visit dance halls and cabarets, where they were free to drink fairly anonymously. In small towns across America, however, there were few places that served alcohol that women could visit without facing the scorn of their neighbors. In some cases, it was actually illegal for women to spend time inside bars because it was associated with sex work. If women wanted to drink, they had to drink at home.

Prohibition changed the way America drank, and in doing so, made it possible for more women to drink in social settings than ever before. As detailed in "Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters: Gender and Prohibition in Butte, Montana," Prohibition did cut back on the amount of drinking, but it also created new environments where Americans spent time and drank together, like nightclubs and speakeasies. These places were already breaking the law, and they were happy to service people of any gender. Some speakeasies, also known as "moonshine joints" or "blind pigs" were operated by women, or by husbands and wives together.

Women participated in organized crime

Prohibition made the sale and use of alcohol illegal, but many Americans never stopped drinking. The void left by legal alcohol selling was quickly filled by gangs, creating a kind of organized crime that the United States had never seen before. As stated by the National Museum of American History, the liquor business became more profitable than ever now that it was an illegal substance. There was intense competition between gangs, which sometimes turned violent and brutal as they protected their territory.

Women were particularly valuable to these operations. As described by Fred Minnick for HuffPost, it is believed that many gangs directly recruited many female bootleggers to work for them. While women bootleggers made, smuggled, and sold alcohol, either for themselves or for a gang, even women who were otherwise uninvolved in the liquor business were useful. Often, they would hire a woman to do nothing but ride in the passenger seat of a vehicle that was moving liquor, because federal agents were unlikely to stop and search a car with a woman in it.

Women transported alcohol

Women manufactured alcohol and women sold alcohol, but more than any aspect of bootlegging, women were the ideal smugglers. Women were confined to very strict social roles — but women bootleggers were able to exploit them for their own gain. Many people found the idea that women could be this type of criminal ludicrous, and authorities often felt uncomfortable even checking if a woman was carrying alcohol.

An agent reported in 1924 (quoted by HuffPost) that a woman they suspected of bootlegging laughed when the police confronted her and "defiantly declared to bring suit against anyone who touched her."

As described in "Whiskey Women," gangs were able to take advantage of a peculiar legal loophole: male Prohibition agents were, in some cases, not allowed to frisk women. This allowed women bootleggers to transport alcohol across the country on their person. "Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era" states that women were able to stash small amounts of alcohol in their underclothes, which was known as "girdle whiskey." Some women took things even further, dressing as nuns while carrying alcohol, which made customs officers even less likely to feel comfortable searching them thoroughly.

Women were less likely to be punished

"I've turned many a widow woman loose and never made a report," J. Carroll Cate, head of the federal Prohibition unit in East Tennessee is quoted as saying, "I did it because ... her children would've had no food."

Even when women were arrested for bootlegging, they weren't as likely to face harsh sentences as male bootleggers. As described in "Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters: Gender and Prohibition in Butte, Montana," in the 1920s, judges and juries often weren't prepared to send otherwise upstanding wives, mothers, and grandmothers to prison for bootlegging. Women who were bootleggers knew this, and they took full advantage. As described in "Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era," judges often gave lighter sentences, or suspended them altogether, when they learned that a woman brought up on bootlegging charges had sold alcohol to provide for her children.

Even women who were fined or jailed often came out ahead. One case described by Fred Minnick for HuffPost involved a woman who made the modern-day equivalent of over $480,000 a year bootlegging. She was convicted and sent to jail for a month — but she was only fined the equivalent of less than $5,000, meaning she still made a considerable profit. Another woman bootlegger was convicted but not given any jail time at all — instead she was told to go to church every Sunday.

It could be dangerous

Many women who were arrested on bootlegging charges would explain to the court that they had only sold liquor to provide for their children. This was usually an effective testimony, especially for widows and single mothers. However, as detailed in "The Feminine Side of Bootlegging" things did not always go as well if they were caught a second time. Often investigations were made to see if these women were actually as poor and desperate as they claimed (which they almost always were). Generally, women who were being charged for the first time were given some leniency as to how long their sentence would be, or when it would begin, to ensure that their children were not left to fend for themselves. This was far less common with repeat offenders.

The process of making alcohol was sometimes dangerous in and of itself. Stills were prone to explosion, sometimes killing bootleggers. Moonshine made incorrectly could also be highly toxic, causing blindness, paralysis, and even death.

Women might have been considered valuable by the gangs they worked for, but that didn't mean that they were always safe from the violence of organized crime. Famous bootlegger Bessie Perri was shot outside her home in 1930. Her murder was never solved.

Bootlegger queens

Despite the many dangers, bootlegging was lucrative enough for women to accept the risks. The newspapers might had dubbed them "bootleggerettes" and the flappers might have called them "snake charmers," but the most successful women bootleggers earned another name: "Queen of the Bootleggers."

As described in "The Feminine Side of Bootlegging," the majority of women bootleggers were working class, often single mothers, attempting to provide for their families. That wasn't the case for all of them, however. One woman named Elizabeth Deffes, who was arrested for selling whiskey with her husband, claimed that she was just selling a little alcohol to be able to afford Christmas gifts for her children (a common and effective defense for women.) In court, her husband admitted that she was actually his agent in the local speakeasy. Some women, like Marie Troila, were married, but did their bootlegging alone while their husbands worked traditional jobs. As described by author Fred Minnick for HuffPost however, some women were at the top of vast bootlegging empires — and every one of them was called a queen.

More than ten women were hailed as the bootlegger queen by the press. One woman bootlegger named Mary White was caught with the modern-day equivalent of almost $80,000 in cash. When reporters asked her if she was The Queen of the Bootleggers, she answered, "I wish the hell I was."

Birdie Brown

As stated by "Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters," Prohibition created an opportunity to start an illegal alcohol business and gain steady income for groups that hadn't been able to before, including women and Black Americans. Some of the era's most powerful bootleggers were both.

As explained by Politico, just as many important womens' rights activists of the era supported Prohibition, so did many abolitionists and civil rights leaders, including Frederick Douglas, Ida B. Wells, and W.E.B. Du Bois. Despite this, in some areas it is believed that the majority of Black citizens were against Prohibition — such as in Florida where they were largely responsible for voting down a 1910 attempt to ban alcohol. As explained in "The Feminine Side of Bootlegging," relatively few Black Americans were charged with bootlegging. It is unclear if the majority of illegal alcohol was manufactured and sold by white people, or if Black communities were simply less likely to report the sale of alcohol than white ones, keeping Black bootleggers from being discovered and arrested.

One of the era's "Queen of the Bootleggers" was a Black woman known as Birdie Brown. As told on historian Ellen Baumler's blog about Montana history, Brown was a homesteader who lived alone in Montana, and she was known to be able to produce safe, high quality moonshine. Her home became a popular parlor. As reported by Forbes, the modern Black women-owned business "Saint Liberty Whiskey" has created a Bourbon in Birdie Brown's honor, known as "Bertie's Bear Gulch."

Cleo Lythgoe

Women bootleggers thrived because the social roles that women had been forced into made people hesitant to see them as criminals. Most did everything they could to keep a low profile. Possibly the most successful of the Bootlegger Queens was a woman named Gertrude "Cleo" Lythgoe — and she had no interest in keeping her success a secret.

As described by Fred Minnick for Huffpost, Cleo was a legal liquor wholesaler prior to Prohibition. When her business became illegal, she left the United States for the Bahamas — but she didn't stop selling liquor. She commissioned her own boats and made deals with Scottish distilleries so she could provide customers with high quality Scotch. Cleo's enterprise was massive, and U.S. authorities did everything they could to stop her, even having a female agent strip search her when she entered the country. That didn't deter Cleo. She often gave interviews to the press and had to carry guns and razors for fighting off competitors and admirers alike. She was showered with love letters. Some offered to marry and provide for her so that she could give up bootlegging — but Cleo wasn't interested in quitting.

Finally, one of her boats was seized by U.S. authorities. It seemed like she might end up in prison. Instead, she testified that her employees had stolen the boat and smuggled liquor without her knowledge. Her bootlegging operation was over, but she had already made her fortune — it's estimated that she made the modern-day equivalent of over 15 million dollars.