Operation Fantasia: The WWII Plot To Fight Japan With Glowing Foxes

Following a bold and unexpected attack on Pearl Harbor, the American war machine came to life, per History. President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared on December 8, 1941, "No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory" (via the National WWII Museum). The nation entered World War II with a flurry of activity.

Men and women rallied to contribute to the war cause. They volunteered in the armed forces, rationed goods, grew "Victory Gardens," and took up factory jobs making planes and other wartime supplies, per the National Park Service (NPS). While television shows, documentaries, movies, and books have thoroughly exploited these wartime activities, more covert and outlandish areas of the war effort have received less attention.

Many of these less well-known activities fell under the umbrella of America's first secret agency, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Picking and choosing the strangest of their operations would prove hard by any stretch of the imagination. Nevertheless, their attempt to invade mainland Japan with radioactive, glow-in-the-dark foxes ranks near the top, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine. Here's everything you need to know about what the OSS termed "Operation Fantasia."

Desperate times called for desperate measures

After Pearl Harbor's surprise attack by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, America dropped into the middle of a global conflict, ill-prepared to fight, according to History. Yet, in the wake of "the day that would live in infamy," retaliation for Pearl Harbor marked the first order of business. American military commanders grasped for straws, creating drastic plans for desperate times.

Naval History and Heritage Command describes one of the gutsiest plans as Doolittle's raid, first designed in January 1942. This surprise attack involved a "joint Army-Navy bombing project" to hit Japan's industrial centers. They hoped to fill the Japanese people with fear, shock, and confusion. But it came at a great price. The ambitious action represented a near-suicide mission for the pilots involved.

Not all attempts to strike fear in the hearts of the Japanese involved bold military operations, as reported by the National WWII Museum. The strangest ones came out of the OSS and involved exploiting everything known about Japan and its people, including mythology. The perfect motto for the OSS would be: "All's fair in war." Especially when it came to inflicting physical and psychological harm in the name of a speedier victory. So, OSS agents got busy, planning out the improbable and the impossible ... like flooding Japan with mythological creatures, representing "omens of doom."

Birth of the Office of Strategic Services

A yellow spearhead on a black background came to symbolize the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), per William K. Emerson's "Encyclopedia of the United States Army Insignia and Uniforms." This symbol fit well with the OSS's self-designated role of spearheading the bizarre, unthinkable, and "just might work" operations of World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the organization on July 11, 1941, to capture and organize intelligence, per the National WWII Museum. Even George Washington relied on an intricate network of spies during the Revolutionary War, so it seemed like a common-sense move. Heading up the OSS, Roosevelt appointed "Wild Bill" Donovan. Donovan would act as the coordinator of information (COI). An honored veteran of WWI and a Columbia Law School graduate, he fit the role to a tee.

Interestingly, appointing Donovan started a trend of hiring lawyers to serve in the OSS. Officials felt few educational backgrounds better matched the agency's scope in terms of devious machinations and creative intrigue. What's more, government officials argued the broad education of a law degree encouraged versatility. Tasked with tracking down "strategic information," the OSS undertook secret missions that "duplicated, but did not necessarily replace, functions carried out by the State Department [and other three-letter departments]" (via the National Archives). That barely scratches the surface of what the agency actually did.

Zany operations dreamed up by the OSS

Smithsonian Magazine reports the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) dreamed up outlandish plans meant to throw off the Japanese and impact the trajectory of the war. And let's just say they left few stones unturned. Some of their plans make the James Bond and Mission Impossible movies look downright boring.

The OSS's dirty tricks included strapping incendiary bombs to live bats and dispatching them to attack Japan's most strategic cities, per Ripley's. The bombs included timers so that bats would have a chance to roost in large groups in homes and buildings, assuring maximum destruction. If this sounds insane to you, then you never would've made a good OSS officer. To work with this group, you had to suspend all logic. President Roosevelt's advisors defended the bat plan reassuring the world that its creator, Lytle S. Adams, "is not nuts!"

Through 1943, the military captured thousands of bats, cooling them to induce hibernation for smooth overseas transport. Test runs with the bats led to mayhem stateside, including the destruction of an air hangar, a fuel tanker, and a car. Oops! Eventually, the competing Manhattan Project eclipsed the bat operation. But the weird strategies didn't stop there. From explosive pancake mix (a.k.a. "Aunt Jemima") to hormone-laced veggies meant to effeminize Adolf Hitler, and the ultimate stink bomb, the OSS stayed busy. Nevertheless, one plan stands out from the rest, Operation Fantasia (via the National Archives).

Operation Fantasia: the zaniest plan of them all

Operation Fantasia represented a highly complex stratagem, spearheaded by Ed Salinger, an entrepreneur who'd done importing and exporting in Tokyo (via Smithsonian Magazine). An OSS psychological warfare specialist, Salinger enjoyed a reputation for zaniness. And he didn't disappoint when it came to bizarre plots.

He first pitched the glowing fox bit to the OSS in 1943, claiming Operation Fantasia would inflict incalculable psychological damage while weakening Japanese morale. In a memo detailing the project, he argued, "The foundation for the proposal rests upon the fact that the modern Japanese is subject to superstitions, beliefs in evil spirits, and unnatural manifestations which can be provoked and stimulated." In other words, he assumed the Shinto beliefs of the average individual would override all other sensibilities.

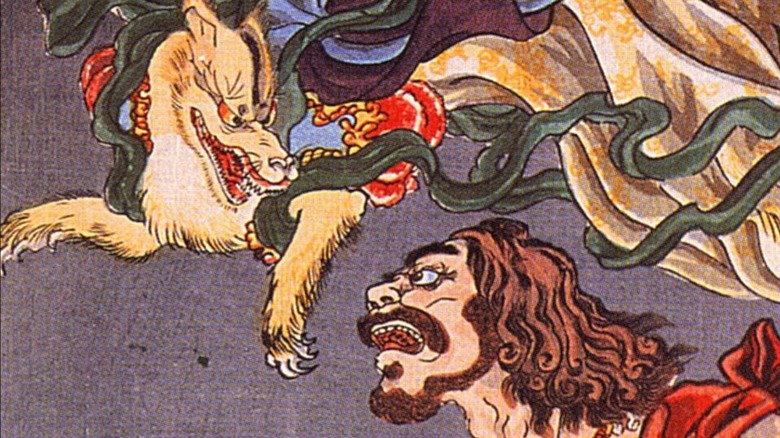

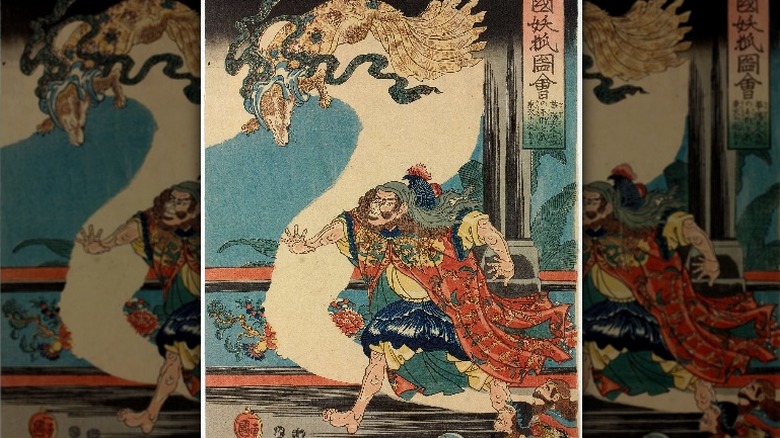

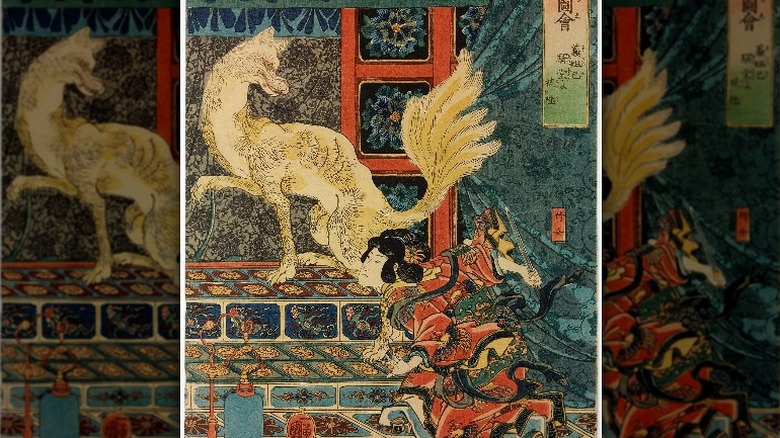

As for the fox, known as kitsune in Japan, he settled on this symbol as a "portent of doom." That doesn't mean it was the OSS's first choice, however. According to the National Archives, they also played around with other potential evil signs, including evil eyes, hexes, and "grotesque animal(s)." The initial idea involved creating a giant weather balloon version of this object and installing it at a visible height of 2,000 feet. After a quarter-hour of viewing, they'd "obliterate it completely." Simple enough. (Not!)

Superstitions, evil spirits, and unnatural manifestations

Ed Salinger's attempts to elicit fear and chaos among the people of Japan sound far-flung today. But enough of his contemporaries got behind the plan to nearly bring it to fruition, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine. Soon, the powers-that-be declared the fox antics "the most potent psychological tool against the Japanese" (via "Psychological Operations American Style: The Joint United States Public Affairs Office, Vietnam and Beyond"). But as Ripley's points out, kitsune enjoyed a more nuanced position in Shinto mythology than Salinger cared to consider. They inhabited many fascinating roles, and all weren't doom and gloom.

Kitsunes could be tricksters, excelling at mischief and metamorphic capabilities, per Britannica. But they also represented messengers of the god Inari, protector of cultivation and rice. Foxes served as faithful guardians, especially over rice fields. So, farmers offered sacrifices to Inari, guaranteeing the protection of his foxy companions. Today, about a third of all shrines in Japan appeal to Inari, demonstrated by the fox statues lining the exterior walkways (via Tofugu).

Some foxes did act as demons, though, harassing humans with malignant behavior. Salinger hoped to scare the bejesus out of locals by exploiting this strain of the myth. The Japanese associated kitsune with kitsunebi or foxfire, which might communicate a "harbinger of bad times." So, Salinger placed a premium on making his "supernatural" foxes glow in the dark. The OSS's attempts to achieve this marked, by far, the most dangerous aspect of the plan. After all, the best way to make things glow in the dark in the 1940s involved radiation.

Problems with Operation Fantasia

The level of gullibility ascribed to the Japanese by Ed Salinger proves mind-boggling. After all, their belief in mystical creatures (a.k.a. the "yokai") mirrored that of cultures worldwide, including Europeans. For example, think about all of the talking animals inhabiting European literature, from Aesop to Beatrix Potter.

In essence, Operation Fantasia represented the equivalent of air-dropping white rabbits with pocket watches into Oxford and assuming British passersby would dive down rabbit holes after them a la "Alice in Wonderland." Or it'd be like letting "Walking Dead-style" zombies loose in Manhattan and watching NYC explode. Sure, Nostradamus supposedly warned of a zombie apocalypse in 2021, and the CDC keeps a tongue-in-cheek web page on the topic (via USA Today). But there's still this thing called common sense.

As Vince Houghton explains in "Nuking the Moon: And Other Intelligence Schemes and Military Plots Left on the Drawing Board," Operation Fantasia epitomized the "breadth of the racism, ethnocentrism, and general disregard for Japanese culture held by many, if not most, of the top American military, intelligence, and political leadership" (via Smithsonian Magazine). Ultimately, the concept of yokai or folkloric creatures permeates all cultures, and it's hard to grasp why the OSS thought the Japanese would prove more vulnerable to it than the Germans or Italians. Yokai represented a way to interpret and understand the world no different than the Valkyries of Teutonic mythos, the vampires of Eastern Europe, or the half-rotted zombies of today.

The fox harassment brainstorming gets hare-brained

Appealing to logic didn't factor into the work of the OSS (as you've likely figured out at this point). And only the most superficial understanding of cultural symbology was required to devise what many in the military and government saw as a genuinely dastardly plan, per Smithsonian Magazine. After all, the organization thrived on the most hare-brained concepts imaginable. So, officials never concluded that Ed Salinger might be a huckster who deserved no more time (or funding) from America's OSS.

Although unbelievable, steps began in earnest to bring Operation Fantasia to life. Initially, they involved cockamamie ideas like creating fox balloons to terrify Japanese villagers and even making a fox scent that the Japanese would somehow recognize, according to "Psychological Operations American Style." Accompanying these physical manifestations of scary foxes would be pamphlets written in the style of local soothsayers, claiming the Shinto equivalent of the end of the world.

Salinger also got behind the idea of manufacturing whistles to simulate fox sounds. He explained, "These whistles can be used in combat, and a sufficient number of these could create an eerie sound of the kind calculated to meet the Japanese superstition" (via Smithsonian Magazine). He doesn't explain how to fill this tall order or what happened the first time a Japanese soldier caught an American blowing the whistle.

Creating kitsunebi for Operation Fantasia

While these endeavors proved a helpful way of supporting Operation Fantasia, they didn't get to the crux of Ed Salinger's grand vision, according to Smithsonian Magazine. He still needed his glow-in-the-dark foxes, by gum! After all, there was little point in exploiting the kitsune image without luminescent, furry creatures to send abroad, terrorizing the countryside.

Moving past the wild brainstorming, the OSS homed in on the original plan, creating glowing foxes to introduce into Japan where they would intimidate locals (and presumably cause them to lose the war). If you're seeing a few leaps of logic in the previous sentence, you're not alone. Anyway, in keeping with the plan, they did the next reasonable thing. They captured live foxes in Australia and China to spray with luminescent paint ... that just happened to be radioactive.

Before we continue with this far-fetched tale ripped from the pages of reality, a moment of silence is in order. It's difficult to fathom the devastating impacts the OSS had on wildlife populations and ecosystems worldwide as they ripped fragile bat colonies from their habitats for bomber expeditions or forced captive foxes to undergo radioactive contamination in the name of "bad B-rated movie" antics (via "Psychological Operations American Style").

Perfecting the art of 'radium foxes'

Creating glow-in-the-dark foxes came with hazards and hurdles. For starters, the iridescent paint they needed to use contained radium, "a naturally occurring radioactive metal," with well-established health risks. Women employed in factories to paint watch details with the stuff had already found this out the hard way. Known as "Radium Girls," they developed everything from tooth loss and migraines to anemia, cancer, and jaw necrosis, as reported by NPR.

But the challenges didn't end there, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Ethical issues aside, the larger question in the OSS's mind remained how to get the radioactive paint to stick to the fox's coats. Again, this difficulty might have inspired another crew to reconsider their efforts. But the OSS moved full steam ahead, turning to Harry Nimphius, the Central Park Zoo's veterinarian, for advice. Nimphius started by experimenting on a raccoon.

Keeping the poor critter under lock and key where no members of the public could see him, he figured out how to keep the luminescent paint in place for days at a time. Once this all-important Operation Fantasia hurdle was surmounted, the OSS decided to show off their handiwork. They terrified countless Americans in the process.

Operation Fantasia inflicted the most psychological damage on Americans

Perhaps the most ironic part of the OSS's Operation Fantasia would prove the amount of psychological damage it inflicted on Americans, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine. Because once the OSS figured out how to make the glowing paint stay on the foxes, they tested out just how effective the animals proved at scaring people, using the residents of Washington, D.C. as guinea pigs.

Releasing 30 of the luminous creatures in Rock Creek Park, they reported smashing success in the form of the "screaming jeemies." After these "favorable" results, the OSS argued the Japanese, due to their cultural programming, would fall for the plan hook, line, and sinker.

Operation Fantasia still required a failsafe way to deliver the glowing foxes to the Japanese mainland, though. So, OSS agents decided to find out how well the irradiated foxes could swim. They loaded them into small cages and went out to sea. Then, off the coast of Chesapeake Bay, they released the bedraggled creatures, forcing them to swim ashore. Fortunately, they managed the feat. But once the foxes arrived onshore, experiment observers realized most of the paint had washed away. What little remained, the foxes licked off.

Failed plans birthed even crazier schemes

You'd think all of these setbacks might eventually make Ed Salinger rethink his plan, per Smithsonian Magazine. But, no, they didn't. Instead, his schemes grew proportionately wilder. Salinger and the OSS decided the foxes must get dropped off on the Japanese mainland, a tall order in the middle of a war.

After that, Salinger concluded the foxes should have the right training to relocate strategically near high populations areas. But whether foxes could even be trained was another matter. He also hoped to play the numbers game to the OSS's advantage, noting, "If enough foxes are released, some will get through." Never a man to go without a Plan B, he suggested getting other creatures involved in the spray painting, too, like muskrats, raccoons, coyotes, and minks.

But Salinger's apparent break with reality didn't stop there. He proposed creating a floating, taxidermied fox with a human skull affixed to its head to terrify the citizenry. Naturally. Salinger argued this faux creature would play on "a peculiarly potent manifestation of the Fox legend." His description of the stuffed monstrosity proved nuanced. He even explained how the human skull's jaw atop the fox would move to simulate talking. To further hedge his bet, he recommended creating an army of Japanese collaborators to feign fox possession. What could possibly go wrong?

The voice of reason (and nukes) prevail

By September of 1943, some members of the OSS had enough of Ed Salinger's attempts to "outfox the Japanese," according to Smithsonian Magazine. They included Head of OSS Research and Development Stanley Lovell. Lovell's nickname was the well-deserved "Professor Moriarty" as he masterminded the estrogen-laced veggies Hitler escapade. (Makes you wonder how they would gain access to Hitler's food supply and why poisoning wasn't an option.) But even Lovell saw the writing on the wall when it came to Operation Fantasia.

As the war drew to a close and the American military placed most of its eggs in the nuclear basket, bizarre-o plans like Operation Fantasia came to a halt. The more logical members of the OSS took this in stride. According to notes from an OSS meeting conducted near the war's close, they reported, "This problem of Fantasia has been mercifully completed."

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought World War II to an end in the Pacific and marked the final nails in Operation Fantasia's unwieldy coffin. From animal cruelty to public experimentation and something well beyond cultural misappropriation, it's hard to pick apart all of the inherent issues with Operation Fantasia. But the strategy paled in comparison to the planet's entry into the Atomic Age. With the 1950s, "duck and cover" drills became the new norm, and radioactive foxes disappeared into the pages of history.