The Radical History Of Bloodletting Explained

Misquotes litter the internet, spreading like wildfire through faulty retellings via Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and other social media channels. One of the most iconic of these sayings is reportedly a part of the Hippocratic Oath, "First, do no harm." But as the National Library of Medicine reports, the original Greek text doesn't include this direct statement. Instead, think of it more like an overarching theme.

The intellectual wellspring from which the Hippocratic Oath sprang can be attributed to the Greek physician Hippocrates of Kos, per Live Science. He lived from 460 B.C. to 375 B.C. and gained acclaim as one of the first individuals to look at illness in a natural rather than supernatural way. Essentially, he argued that curing ailments required proper upkeep rather than devotion to the gods. He dedicated his life to creating the first intellectual school of medicine, earning a reputation as the "father of medicine." Hippocrates and his students produced 60 medical documents still preserved today and unified by the concept of a "healthy mind in a healthy body" (via the Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine).

But one of Hippocrates' most famous medical theories, the four humors, inadvertently led to incalculable harm for centuries, leaving a veritable blood bath in its wake. It involved the practice of bloodletting, considered an essential tool in reestablishing balance in the four humors through the removal of excess liquids. Keep reading as we explore the radical history of bloodletting and some of its most famous victims.

Bloodletting boasts a 3,000-year history

According to the British Columbia Medical Journal, the ancient Egyptians first documented bloodletting (aka venesection) roughly three millennia ago. But they didn't enjoy a monopoly on the practice for long. Soon, everyone from the Greeks and Romans to the Arabs and some Asian groups would let the blood spill in the name of healing. One of the world's oldest and most universal medical practices, bloodletting enjoyed broad application, whether you suffered from a fever or a migraine, per History. (It also filled the gap for just about every condition in between.)

The practice continued throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, both culminating and falling into question in the Western world during the 19th century. That said, books such as Heinrich Stern's "Theory and Practice of Bloodletting" still advocated for the practice into the early 20th century. Writing in 1915, he predicted a bright future for phlebotomy, arguing, "Whoever has devoted some attention to the periodical literature on bloodletting knows that in the last 10 years, the number of advocates of this remedial procedure has increased and that of its opponents decreased."

Fortunately, Stein remained (mostly) dead wrong when it came to this prediction. Yet, it demonstrates how recently bloodletting got lauded as a cure. To play devil's advocate, the practice continues today for a narrowly circumscribed list of diseases. (We'll explore this later.)

The paradigm of disease that made bloodletting legit

More than two millennia ago, Hippocrates first steered people away from supernatural explanations regarding natural ailments of the body (via the British Columbia Medical Journal). Instead of sending sick people off to make sacrifices to the gods, he counseled them to participate in holistic health management that involved eating better, regular exercise, and even art therapy, per the Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine. Sound familiar? If so, that's because Western medicine still takes significant cues from him.

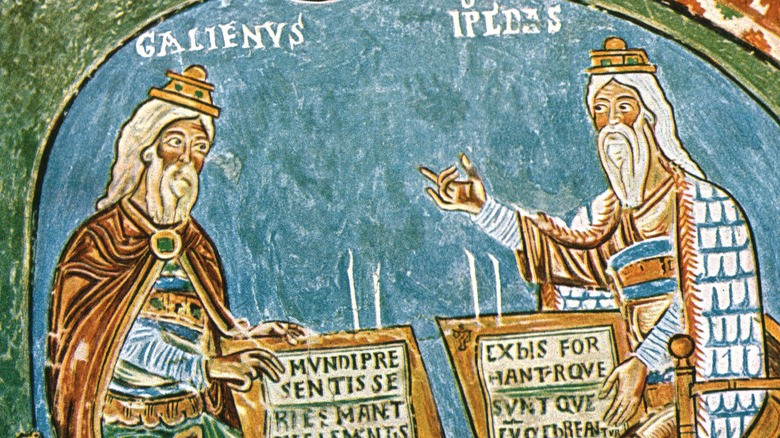

Hippocrates represented a man ahead of this time, except when it came to the disease paradigm to which he subscribed. He perceived disease in terms of four basic elements: air, earth, water, and fire. Hippocrates and his students related these to four humors in human beings: phlegm, black bile, yellow bile, and blood. In other words, illness stemmed from too much of a good thing when it came to an imbalance of humors.

To right such a situation, physicians naturally advocated for the removal of the excess humor. Unfortunately, this removal required some really unpleasant treatment options: purging, catharsis, diuresis, and bloodletting, to name a few. But phlebotomy as the be-all, end-all of cures didn't have a firm foundation until the first-century medical figure Galen of Pergamum (via Heinrich Stern's "Theory and Practice of Bloodletting"). Concluding that blood marked the dominant culprit in 99 percent of diseases, you could say he put venesection on the map. Soon, everybody was doing it.

Venesection could take various forms

Bloodletting techniques varied depending on what the doctor hoped to achieve therapeutically, according to Walton Dutton's "Venesection: A Brief Summary of the Practical Value of Venesection in Disease, for Students and Practicians of Medicine." As with parallels between human and veterinary medicine today, animals also got in on the venesection action.

"General bloodletting" involved draining blood from a large vein or artery (typically the elbow's median cubital vein). The goal of "general bloodletting" remained simple: reducing the overall amount of blood in the body. As for "local bloodletting," it relied on various approaches to achieve the desired effect. For example, a physician might use cupping, leeching, or scarification to induce blood loss to a specific "neighborhood" of the body.

The British Columbia Journal of Medicine describes the nuances of local bloodletting, explaining that scarification required doctors to scrape the patient's skin with what looked like an innocuous brass box. But inside, it contained many small knives for localized butchery. As for leeching, the name says it all — the procedure relied on the slimy, blood-sucking critters to devour unwanted blood from the body. Last but not least, cupping used dome-shaped cups placed on the skin to create blisters through suction. Once the cups were placed, physicians achieved suction through heat or vacuum removal of air.

The transition from monks to barbers

During the Middle Ages, physicians relied on venesection to treat everything from epilepsy to the plague, per History. Up through the 12th century, sick people visited their neighborhood monk or priest for such procedures. But by 1163, the church banned the practice, declaring it "abhorrent." Soon, barbers stepped in to fill the void, offering shaves and trims along with tooth pulling, bleeding, cupping, and even amputations. These barber-surgeons hung red and white blood-smeared rags outside to advertise their services. If this sounds familiar, it should — scarlet and white barber pole stripes evoke this barbaric imagery today.

Barber-surgeons retained a central role in bloodletting for centuries, even when physicians recommended the procedure. To avoid getting blood on their hands, physicians often recommended their patients go to barber-surgeons to have the dirty work of bloodletting done, as reported by Brewminate. Some physicians and barber-surgeons even advocated for bloodletting to prevent illness in the first place. Although visiting a barber that dabbled in bleeding on the side sounds sketchy at best, it's important to note that the separation of physicians and barber-surgeons set the stage for one of the most critical distinctions still found in medicine today: doctors versus surgeons.

The bloodletting tools of the trade

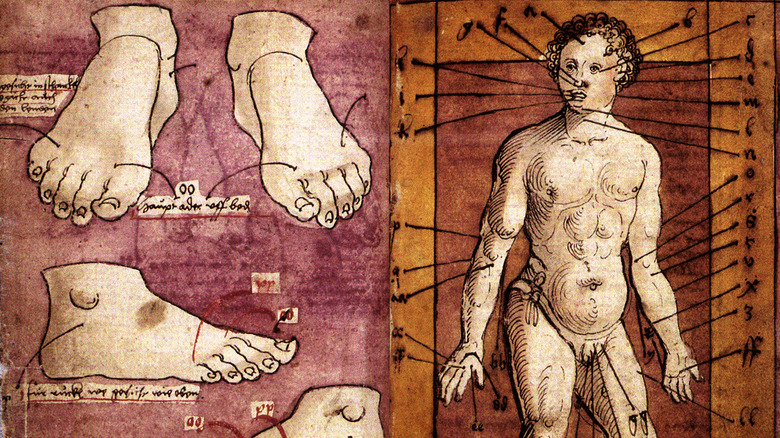

Physicians involved in bloodletting packed a variety of tools in their medicine bags. According to the British Columbia Medical Journal, these tools included thumb lancets, fleams, dome-shaped glasses for cupping, a small brass box filled with knives for scarification, and leeches. Thumb lancets came in tortoiseshell or ivory cases, making them instantly recognizable. These double-edged instruments had sharp points that made "breathing a vein" (as doctors and barber-surgeons called it) a cinch, Brewminate reports.

Physicians generally targeted the body's large, external veins, targeting those found in the neck or forearm. But in the scariest cases, doctors practiced arteriotomy, where they opened an artery. Physicians generally stuck to arteries in the temple for such procedures, and thumb lancets proved incredibly helpful in these situations. So did fleams, sets of blades in various sizes that tucked into a case reminiscent of a pocketknife.

We've already talked a bit about scarifications and cupping, but what were the specifics when it came to leeching? The leech of choice proved the aptly named Hirudo medicinalis, capable of sucking approximately 10 times its body weight (between 5 and 10 milliliters) of blood. By the 18th century, innovations in these tools (e.g., the scarificator and spring-loaded lancets) made general and local bloodletting a little less excruciating.

Mesoamerican bloodletting took a different twist

Before Christopher Columbus saw the New World, the Maya practiced bloodletting, per Jessica Munson et al.'s study in PLOS One. Rituals included piercing lips, tongues, genitals, and whatever else a sharpened stone implement might pass through. The greater the pain and blood loss, the more meaningful the sacrifice. The researchers refer to these displays as "costly ritual behaviors." But Munson et al. hypothesize that bloodletting rituals did more than underscore religious fervor — they also provided cohesion within Maya society. For this reason, bloodletting permeated every stratum of society, from elite priests to average warriors. Maya iconography depicts men from all walks of life piercing parts of their bodies — especially tongues, ears, cheeks, and penises — to release the red stuff. Besides using sharp stone implements to get the gore rolling, Maya codices depict bone awls, stingray spines, and lancets with bowls in use.

Ethnohistorical accounts of eyewitnesses like Diego de Landa also provide valuable details. As quoted in Munson et al., de Landa observed, "Sometimes they scarify certain parts of their bodies, at others they pierced their tongues in a slanting direction from side to side and passed bits of straw through the holes with horrible suffering, others slit the superfluous part of the virile member leaving it as they did their ears." In a world where favor from the gods meant robust health and long life, think of bloodletting as a divinely-inspired prophylactic.

The Parisian doctor who made leeching trendy

For those left cold by genital mutilation with stingray spines, France offered a gentler approach to bloodletting: leeching. The Parisian doctor François-Joseph-Victor Broussais made Hirudo medicinalis (medical leeches) trendy, treating various ailments with the little guys. Soon, he earned the title "le vampire de la médecine" for his bloodletting enthusiasm, according to JSTOR Daily.

He used 50 parasites at a time to drain his patients, and each one could remove between 5 and 10 milliliters of blood per treatment. Do the math, and you see why Broussais' method amounted to medical vampirism. Nevertheless, Broussais' impact on 19th-century medicine in France can't be overstated. By the 1830s, an army of 35 million leeches serviced the blood-draining needs of the French populace. Broussais' typical treatment protocol included placing 30 leeches on the body and prescribing a fast from food, per Cheryl Halton's "Those Amazing Leeches."

But Broussais proved far from the only individual enraptured by medicinal leeches. Arthur Everett Shipley, a British zoologist, waxed downright rhapsodic about them (via JSTOR Daily): "There is no doubt that the medicinal leech is one of the most beautiful of animals ... a beautiful soft symphony of velvety browns and greens and blacks." He also referred to their movements as "seductive." Although Shipley's sentiments seem a bit over-the-top, leeches came with welcome advantages. Notably, they proved less traumatic than gore-covered barber-surgeons, and leeching came with minimal scarring.

Money bought a torturous death for Louis XIII

Medical treatments require money — lots of it, if you live in America, according to Investopedia. For example, one broken leg can cost $35,000 to fix (via Talk to Mira), and prescription drug costs remain through the roof (per Vox). But in the 17th century, monetary advantage and a slew of doctors at your side pretty much ensured a torturous death. Take the astonishing case of King Louis XIII.

He enjoyed the best money could buy when it came to hedging off disease. His royal physicians proved so aggressive that he endured up to 47 phlebotomies in one year alone (via Heinrich Stern's "Theory and Practice of Bloodletting"). But this is nothing compared to one of the king's attendants, who underwent 64 venesections that year. Healthline reports that bloodletting sessions typically lasted until a patient fainted — give or take 20 ounces for most people. But the torture didn't stop there — post-bloodletting involved "heroic purgings." (Yes, it's as bad as it sounds.)

Despite a lifetime of extreme bloodletting, Louis XIII developed tuberculosis of the intestines. On April 13, 1643, doctors informed him the condition would kill him, but not before they tortured him some more. A steady routine of bleedings and enemas likely made Louis XIII beg for the end, which happened one month later on May 14, per Britannica. Following his death, a detailed autopsy revealed intestinal perforations, ulcerations, and peritonitis, per N.V. Addison's "Abdominal Tuberculosis: A Disease Revived."

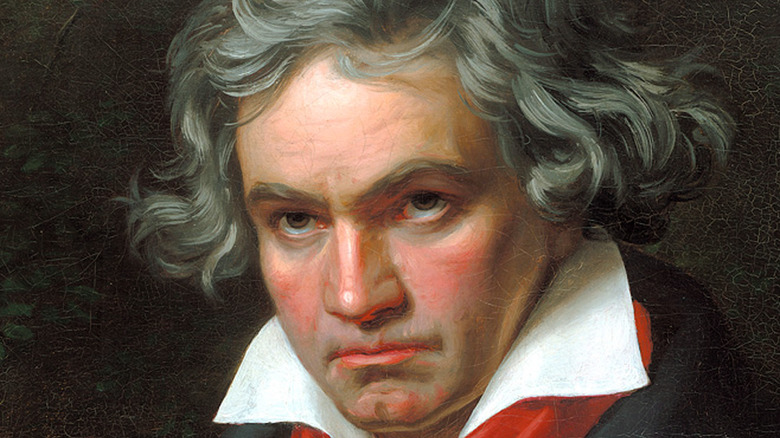

Leeches and Ludwig van Beethoven

Not all cases of physician intervention ended so tragically. Correspondence indicates the 19th-century German composer Ludwig van Beethoven endured local bloodletting, per Francois Mai's "Diagnosing Genius: The Life and Death of Beethoven." According to Interlude, Beethoven suffered from several ailments throughout his life that would've necessitated venesection, according to physicians of the day. These physical problems included diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fevers, which were constant companions since childhood.

As an adult, he added headaches, toothaches, and body aches to the list of symptoms. In a letter from Dr. Johann Schmidt, the physician recommended leeching to help with the composer's headaches, which Schmidt (via "Diagnosing Genius") termed "gout-related." Mai notes that the mention of gout likely indicated the composer suffered from body aches or joint pain. According to the BBC, Beethoven's conversation books reveal he indulged in a daily diet that invited the disease, settling on beef with caper sauce, pigeon pie, and roast veal at most meals. Schmidt also mentions that Beethoven underwent tooth-pulling to ease his throbbing head.

Of course, Beethoven's biggest complaint remained hearing loss "exacerbated by severe tinnitus" (via the BBC). Mai suggests leeching may have even been used to treat the composer's encroaching deafness. While a visit from parasitic leeches didn't kill Beethoven, it didn't appear to cure him, either. Especially if Mai proves right about Beethoven seeking the solace of "seductive" medicinal leeches to improve his auditory abilities.

Treating Charles II of Scotland to death

Ludwig van Beethoven dodged the bullet when it came to death by physician (at least for a while), but other famous people didn't prove as lucky. Consider King Charles II of Scotland. New Scientist reports that after suffering a seizure, royal physicians pounced on the monarch, treating him with immediate venesection. They removed 16 ounces from an incision in the king's left arm, which sounds relatively gentle compared to Louis XIII (via the British Columbia Journal of Medicine). But that was just the beginning.

Next came the removal of another 8 ounces through cupping. After the bloodletting, the real fun began — physicians kept Charles II busy with constant enemas, purgatives, vomit-inducing emetics, and mustard plasters. Mustard plasters alone cause skin inflammation, painful blistering, and even severe burns, but Charles II's doctors weren't done. Science History Institute tells us they scalded him with hot irons and cups, covering him from head to toe in excruciating blisters. Thanks, but no thanks.

Once he'd endured this brutal treatment, which even required drinking "boiled spirits from a human skull," the bleeding started again, per the New Scientist. This time, they tapped directly into his jugular until he fell into a coma. Thankfully (at least from his point of view), he never woke up again, dying on February 6, 1685. Burned and blistered, dangerously deficient in blood, and forced into countless enemas, the medicine of Charles II's day made the certainty of death inviting.

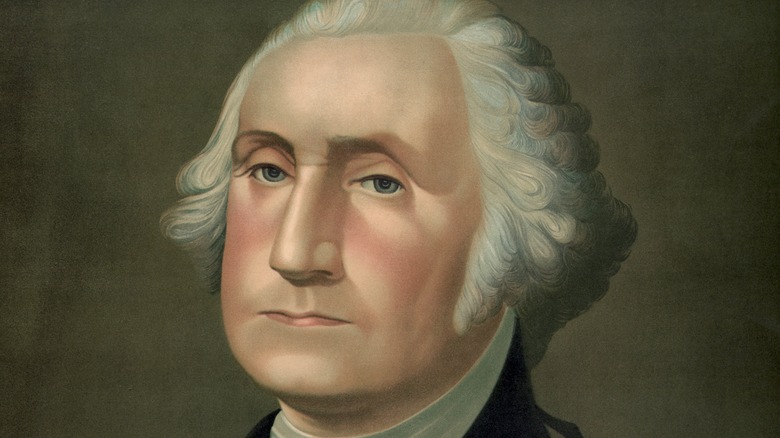

Sending George Washington into shock

Sadly, not much changed on the medicine front from the 17th to 18th centuries. According to the British Columbia Medical Journal, President George Washington's final illness and death prove another cautionary tale of what calling the doctor got you a couple of hundred years ago. One thing's for sure: if illness didn't kill you, doctors would.

Washington's demise-by-doctor began after catching a cold while riding in snowy weather. Soon, a scratchy throat and slight cough gave way to a full-fledged fever and congested chest. Three physicians assessed him, including Dr. James Craik. Not wanting to take any chances with the first president of the United States, they opted for aggressive treatment. (You may think you know what's coming, but it's worse.)

Bloodletting quickly gave way to extreme bloodletting. Before the physicians finished, they'd drained nearly 40 percent (!) of Washington's blood (via PBS). In between draining his life's blood, they gave him herbal teas and an enema for good measure. But the real salvo came when they forced him to drink a mixture of vinegar and molasses butter that nearly choked him to death on the spot. Still not satisfied with their attempts to kill — we mean heal — their patient, Dr. Craik applied a "toxic tonic" to his tonsils, causing painful blistering and swelling (via History). Within 24 hours, Washington lay dead from epiglottitis and shock.

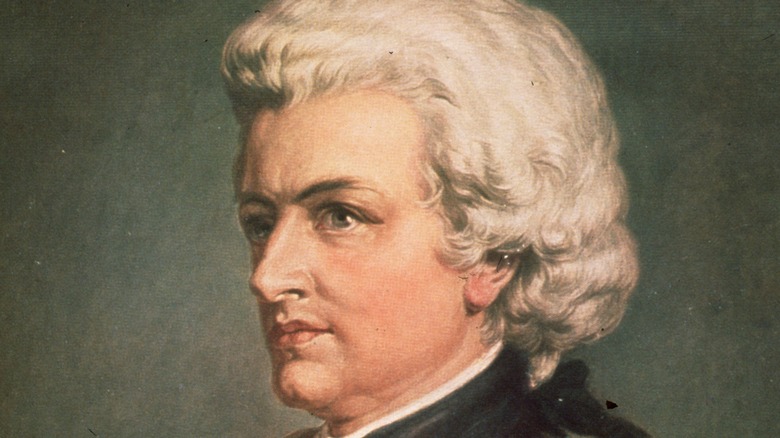

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died of something and bloodletting

Countless theories swirl around Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's ultimate cause of death, according to the Orlando Sentinel. Physicians have spent the last couple hundred years trying to decipher this medical mystery, putting forth everything from poisoning to kidney disease, strep infection, tuberculosis, or even assassination by Freemasons.

The mystery of the genius' abrupt end starts with his death certificate. Unable to verify his ailment definitively, attending doctors named his cause of death as a "heated military fever," a catch-all term for the inexplicable (per Orlando Sentinel). That said, Simon Jong-Koo Lee points out in his article "Infective Endocarditis and Phlebotomies May Have Killed Mozart" in Korean Circulation Journal that this terminology might also refer to fevers accompanied by a skin rash. The New York Times has put forth streptococcal infection as another possibility, and Lee also mentions that such an infection could cause "acute and severe heart failure."

But we do know Mozart's recovery chances stopped the moment he called in his physician, which resulted in — you guessed it! — heavy bloodletting. Correspondence between Mozart's sister-in-law, Sophie Heibel, and Georg Nikolaus Nissen, author of the first comprehensive biography of the composer, reveal Mozart died within two hours of his last doctor's visit. Heibel observed (per Korean Circulation Journal), "On the night Mozart died, Dr. Closset arrived and bled him then ordered cold compresses be placed on his burning head, which was such a shock to him that he never recovered consciousness before he expired."

Marie-Antoinette's bloodletting worked wonders

Every now and again, phlebotomies actually appeared to work, and some scholars believe this is why monks, barbers, and physicians stuck in the game with the treatment for so long (via History). For example, before the birth of her first child, Marie-Thérèse, Queen Marie-Antoinette underwent venesection. At the time, curious courtiers piled high in her bedroom, hoping to catch a first glance of what they wrongly presumed would be a dauphin or male heir to the throne. Their impending disappointment aside, we can only imagine how hot and stuffy the room became as what should've been a private event took place before the masses.

Suffocated by the awful situation, Marie-Antoinette eventually fainted. In response, her attending physician bled her while servants simultaneously opened her bedroom windows to let in a little fresh air. While the introduction of fresh air most likely revived Marie-Antoinette, the royal physicians heartily accepted credit for her impressive recovery and the successful birth of a healthy little girl dubbed "Madame Royale," per the Château de Versailles.

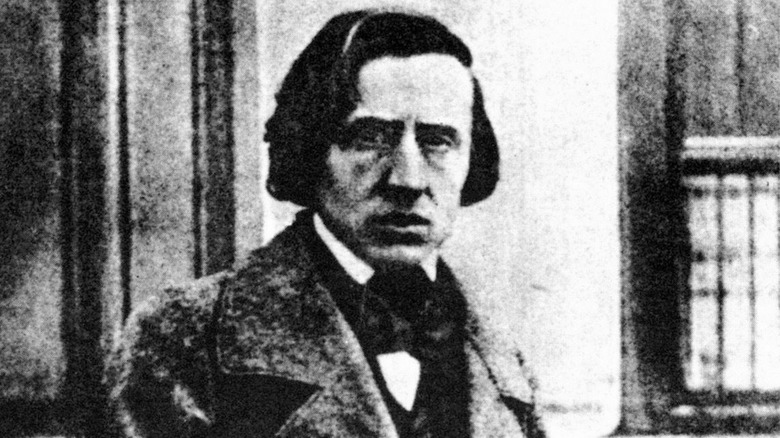

Frederic Chopin cupped but drew the line at bloodletting

Another death modern researchers puzzle over is that of the famed composer Frédéric Chopin, as reported by Victoria Wapf's "The Disease of Chopin: A Comprehensive Study of a Lifelong Suffering." Although most people assume he died from tuberculosis, a handful of researchers have put forth other diseases like cystic fibrosis. What we do know for sure is that his life remained plagued by serious illness, leaving him weak and coughing up blood.

Interestingly, the Polish composer refused to undergo general bloodletting. Wapf argues that he had at least two compelling reasons for skepticism about venesections. First, he watched his sister, Emilia Chopin, die after days of massive bleedings to treat anorexia. In a letter to a friend dated 1827, he wrote (per "The Disease of Chopin"), "The bloodletting, which was done once, twice, innumerable leeches, vesicle-producing plasters, mustard plasters, and herbs, adventures over adventures". Emilia Chopin died within a month, and her brother never forgot the lesson she taught him about bad medicine.

Second, one of his doctors, Pierre Charles Alexandre Louise, proved outspoken against bloodletting, citing statistical data to demonstrate the procedure did far more harm than good. Yet, Chopin did give into some aspects of 19th-century treatment protocols, including dry cupping and "blister plasters." Considering the severity and duration of his illness, it's remarkable he avoided more meddling on the part of physicians.

Opposition to phlebotomy is older than you think

Breaking a medical paradigm 3,000 years in the making didn't prove an easy feat, especially when a handful of diseases existed for which bloodletting could bring relief. And, of course, enough coincidences existed to make the practice look at least mildly successful. Nevertheless, as early as the 18th century, a handful of scientists and physicians started opposing bloodletting, per the Journal of Lancaster General Hospital.

These physicians included individuals like René Laennec, inventor of the stethoscope (via the Association of American Medical Colleges). And Chopin's physician, Dr. Pierre Charles Alexandre Louise, was the first to present statistical evidence showing just how ineffective and even dangerous phlebotomy could be. Because of his innovative approach to medicine, Louise is considered "the father of modern epidemiology," according to the Journal of Lancaster General Hospital.

Still, debates raged on the topic throughout the 19th century as people continued to drop dead from the indiscriminate practice. Fortunately, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch put the nails in bloodletting's coffin with their germ theory. This new paradigm of disease rendered the humoral concept obsolete, and millions of happy sick people finally got to keep their blood and their lives. Of course, hangers-on would continue into the 20th century, arguing the merits of a good bleed. Over time, though, their voices fell silent.

Bloodletting persists today

Although bloodletting proves rare today, some vital applications for this therapy exist, per the Journal of Lancaster General Hospital. For example, doctors treat hemochromatosis and porphyria cutanea tarda with venesection. Left untreated, these conditions lead to organ damage due to too much iron in the body. But regular removal of blood does the trick. It also reduces the thickness of the blood, averting clotting complications.

But perhaps the most utilized and promising area of bloodletting involves leeching. Those "beautiful ... velvety" leeches (via JSTOR Daily) we discussed earlier are used with great success to promote blood flow after microsurgery and reimplantation. Leeching works because these parasites make substances like fibrinase, vasodilators, anticoagulants, and hyaluronidase and release them into the patient's system. These naturally occurring chemicals ensure an interruption-free meal while providing patients with the healing benefits of unrestricted blood flow. Hirudo medicinalis has also proven to be an excellent collaborator in the healing process post-plastic surgery, via I.S. Whitaker et al.'s "Hirudo Medicinalis and the Plastic Surgeon."

Wet and dry cupping has also enjoyed a revival in the United States due to influences from traditional Chinese medicine. Unlike leeching, however, data on the effectiveness of cupping prove scant, which has led many physicians to label it a waste of time and money. Fortunately, more egregious forms of bloodletting — like hacking into jugular veins or draining half a person's bodily fluids — have disappeared along with the indiscriminate use of emetics, enemas, and blister-producing plasters.