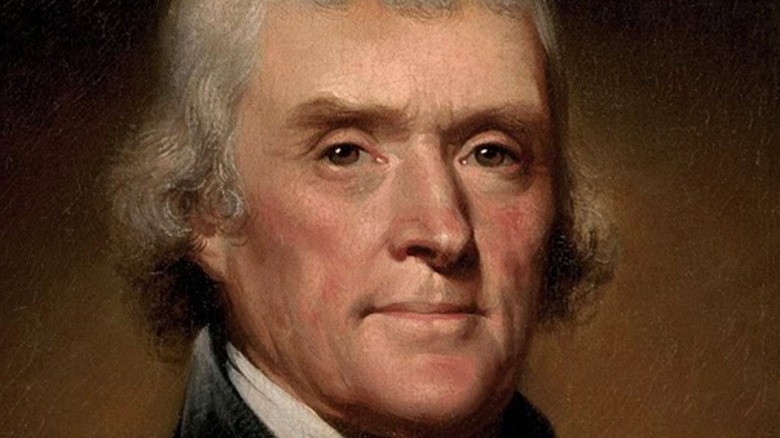

Here's Who Inherited Thomas Jefferson's Money After He Died

It's July 4, 1828, and Thomas Jefferson is dying. His last days are spent at his neoclassical plantation home, Monticello. His health had declined over the past eight years after visiting Warm Springs, Virginia. There, he contracted an infection from the mineral baths. Though he still took daily horse rides and his wit stayed intact, he suffered from a worsening combination of illnesses. His ailments included kidney infection, swollen joints, and pneumonia (via Monticello). Bed-ridden for eight days by that point, Jefferson remained somewhat lucid.

That morning, he woke up to the sounds of a jubilee — bells ringing and cannon fire — celebrating the Declaration of Independence that he penned 50 years prior. Jefferson's servant asked, "Do you know, Sir, what day it is?" He replied, "O yes! ... It is the glorious 4th of July — God bless you all" (per The Saturday Evening Post).

An hour before his death, some of his guests and jubilee party-goers gathered around the third president's bed. They asked if he'd like to provide a toast they could give that evening. He replied, "I will give you 'Independence forever.'" When asked if he'd like to add anything else, he retorted, "Not a syllable" (via The Saturday Evening Post). Within hours of Jefferson's death, John Adams, Jefferson's friend and sometimes rival, died in Quincy, Massachusetts. The country lost its second and third president on the same day (per The Saturday Evening Post).

Settling two presidential estates

Though Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died on the same day, settling the two presidents' estates could not have been more different. While both incurred significant amounts of debt in their lifetimes, John Adams died debt-free and possessed 275 acres of land. His son, John Quincy Adams, rescued his father by selling a house and cashing some investments. Thanks to his son's bailout, when John Adams died, he could bequeath both land and books to Quincy, Massachusetts, to start a school (per The Saturday Evening Post).

Things did not run so smoothly for Thomas Jefferson, and much of what he bequeathed in his will never made it to his intended recipients. Jefferson was in debt for most of his life due to several factors. Much of his income relied on agriculture (not his strongest skillset), compounded with a lavish lifestyle and debts inherited from family and friends (via Monticello).

Jefferson spent his last months scrambling to sort out his affairs. He knew that he'd been afforded lenience as a founder of the constitution and former president. Should his debts pass down to his daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, she would not receive the same lenience. So, Jefferson and his grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, devised a scheme to resolve their financial woes: a lottery (per The Saturday Evening Post).

A disappointing outcome

To settle Thomas Jefferson's debts before his death, he and his grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, put up most of his properties to a lottery. Though initially well-received, the lottery was halted when a group of well-meaning citizens from New York offered to raise the money instead. To their disappointment, the money raised didn't come close to the amount needed. In the meantime, the lottery had lost much of its steam (per The Saturday Evening Post).

Ever the optimist, Jefferson died believing that the lottery would solve his dire financial situation. His daughter, Martha, said that "he died tranquil," so strong was his hope for the lottery (via Monticello). He even wrote to his grandson, "as these misfortunes have been held back for my last days, when few remain to me. I duly acknowledge that I have gone through a long life, with fewer circumstances of affliction than are the lot of most men" (per The Saturday Evening Post). His optimism did not match reality, and the public's enthusiasm for the lottery dwindled. Eventually, his family members canceled the lottery entirely.

After Jefferson's death, his daughter Martha inherited his debts, as he'd feared. In 1831, she sold Monticello and the 130 enslaved people held in bondage there (via The Saturday Evening Post). Eventually, his grandson took on paying back his grandfather's debts, the last payment occurring 50 years after Jefferson's death (per Monticello).

Freedom for only a few

Thomas Jefferson, who penned, "all men are created equal," famously had an ambivalent relationship with the true meaning of the words. Smithsonian Magazine reports that Jefferson traded his early abolitionist beliefs for the profits that chattel slavery afforded him as a plantation owner. Historian David Brion Davis writes, "He was one of the first statesmen in any part of the world to advocate concrete measures for restricting and eradicating ... slavery." Later, however, Jefferson's protestations "virtually ceased" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

As George Washington was planning emancipation at Mount Vernon, having disavowed slavery, Jefferson mortgaged the enslaved people he held to build Monticello (per Smithsonian Magazine). Out of the over 600 enslaved people held on his estate over his lifetime, Jefferson had only freed two before his death. His will only freed five more (via The Washington Post).

The auction block meant family separation for the rest of the enslaved people held at Monticello. Families were sold to as many as eight different buyers. The families of the five freed people were not spared from separation either. Joseph Fossett, freed by Jefferson's will, described watching each of his family members "put up on the auction block and sold like a horse." He worked for 10 years to buy the rest of his family's freedom. In the end, he was only able to save his wife, while his four children remained enslaved.

What happened to Sally Hemings?

The brothers Madison and Eston Hemings were two of the enslaved people freed by Thomas Jefferson's will. Historical records and DNA evidence point to Jefferson as their biological father (per The New York Times). Much is unknown about the nature of the relationship between Jefferson and their mother, Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman held at Monticello. Jefferson fathered her six children, starting from when she was 16 years old (via Monticello). Leslie Greene Bowman, president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, discusses the complexities of writing about their relationship for Monticello visitors: "We really can't know what the dynamic was." She explains to The New York Times, "Was it rape? Was there affection? We felt we had to present a range of views, including the most painful one."

We do know that Sally Hemings negotiated for the freedom of her children. Hemings accompanied Jefferson's family to Paris, experiencing legal freedom and the vibrant cultural, artistic, and intellectual milieu. Two years later, pregnant, she refused to return to Virginia unless Jefferson agreed to "extraordinary privileges" for herself and freedom for her future children. Her daughters, Beverly and Harriet, were allowed to leave Monticello four years before Jefferson's death. Though never officially freed, they slipped into white society, undiscovered but unable to mention their roots or heritage (via Monticello). Jefferson never freed Sally Hemings. After Jefferson's death, his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph unofficially freed her and allowed her to move to Charlottesville, Virginia, to live with her sons (via Monticello).

What else is in Jefferson's will?

In addition to the Monticello plantation, Thomas Jefferson owned and ran the Poplar Forest plantation. Jefferson inherited the 4,819 acres in Bedford Country, Virginia, from his father-in-law in 1773. Used primarily for tobacco, overseers and roughly 100 enslaved persons held in bondage operated the plantation (via Monticello). The estate served as a favorite retreat.

Jefferson turned over the property to his grandson, Francis Wayles Eppes, in 1822, at the time of Eppes' marriage. Later, upon hearing of his grandfather's financial difficulties, Eppes tried to return Poplar Forest, but Jefferson refused. Later, Jefferson's will officially bequeathed the plantation to Eppes. Two years later, Eppes sold Poplar Forest and relocated to Florida, establishing another plantation, L'Eau Noir (per Monticello).

Like much of Jefferson's wishes, his debts compromised his personal library's fate. His will expresses his desire to donate his books to the University of Virginia. However, to settle his debts posthumously, the contents of Monticello's library were sold at two estate sales, one in Washington D.C. and another in Philadelphia. Francis Eppes followed suit and sold the Poplar Forest library in New York City in 1873 (via Encyclopedia Virginia). Thomas Jefferson's will seems to be a fitting final document for the former president. The contradiction between his wishes and the reality at hand speaks to his complex legacy.