What It Was Like To Go To A Vaudeville Performance

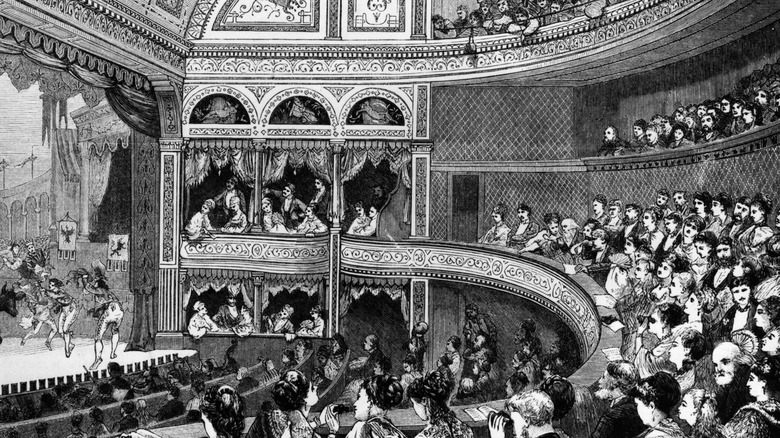

Vaudeville flourished as America's main form of popular entertainment from the 1890s to the early 1930s. For people who went to see the show, it was an exciting and unpredictable experience that allowed them to see a variety of different acts in a single night. As stated in Britannica, the show might include singing, dancing, acrobatics, juggling, and even wild animals.

Without TV or radio, Americans had less access to entertainment — particularly if they lived outside a big city — and vaudeville created an opportunity for average people to see incredible things. Many of vaudeville's most popular performers, such as Mae West and Lillian Russell, would go on to be film stars. In many ways, vaudeville was the beginning of the modern entertainment business.

Very few vaudeville acts were ever recorded. As stated in the Library of Congress, early filmmakers were interested in vaudeville, but though some performers put on acts similar to their vaudeville routines for the camera, no one was ever able to record a live performance of an entire show. While it might be impossible to watch one of these historic events in their entirety today, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, millions of people flocked to theaters to watch vaudeville shows. This is what it was like to go to a vaudeville performance.

Vaudeville was popular

People looking to see a vaudeville show had many to choose from, and often they wouldn't have to travel very far. Vaudeville was an American pastime, and it could be found all across the country, particularly in major cities like Chicago or New York. As explained by PBS, one didn't have to live in a big city to see a vaudeville show — often, small-town stages put on performances, too. As described by Britannica, by the end of the 19th century, there were even vaudeville chains, with one manager running multiple shows. The largest of these had at least 400 theaters.

Those who went to see vaudeville shows had something exciting to talk about with their friends, many of whom had probably seen a show, too. As stated in "Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925," before Americans had access to music on the radio or movies in theaters, the major popular entertainment that most Americans shared was vaudeville. As stated by the University of Virginia, vaudeville transformed entertainment into big business. More than 25,000 performers put on these acts over the 40 years that vaudeville was at its height, and at least 5 million people a week went to see a vaudeville show.

The whole family could come

In the 1850s, variety shows — vaudeville's predecessors — began to sprout up, providing entertainment in big cities and frontier settlements alike. As described by PBS, these shows were generally comedies, full of crude, bawdy jokes designed to appeal to their almost entirely-male audiences. At the time, this kind of humor was considered too much for women. In 1881, however, performer Tony Pastor decided that he would make more money if more types of people would enjoy the show. In doing so, he changed the experience of going to a vaudeville show forever.

As detailed by Britannica, Pastor started advertising his vaudeville theater in New York City as the first that was "catering to polite tastes." His profits skyrocketed, and soon, vaudeville shows around the country followed his lead and started to make their shows more family-friendly. Eventually, that would become the norm, and many people who went to see vaudeville shows brought their families along.

If people turned out to see a show on a Friday night, it was likely that they would find themselves in an audience with many, many children. Mae West, quoted in "Vaudeville U.S.A.," stated that the most popular time for families to go see a vaudeville show was on a Friday night since the kids wouldn't have to get up early for school the next day.

The shows and their audiences were multicultural

Seeing a vaudeville performance could show audiences traditions from home and expose them to cultures they knew very little about.

Vaudeville shows and their audiences were incredibly diverse. As described for the University of Missouri, immigrants from all around the world became vaudeville performers. As noted by PBS, many vaudeville performers were families who used their heritage as a jumping-off point for their performances, making them a part of American popular culture. Notably, Molly Picon, whose parents were Polish, drew on Yiddish theater traditions for her acts. Elsewhere, Black comedian, singer, and actor Bert Williams became a star for his vaudeville performances, which broke racial barriers in entertainment. Some even credit him for changing many Americans' minds about racial equality (though many of his performances were done in blackface, making him a controversial figure). Many of the vaudeville performers were working-class and came from a variety of cultures and ethnic groups. However, as noted in the Library of Congress, many jokes relied on ethnic caricatures and stereotypes — often of the same groups that were performing and watching them.

The variety of acts attracted a variety of people to the audience. As described by Mae West (quoted in "Vaudeville U.S.A."), the same show could attract entirely different audiences on different nights. Sometimes wealthy, high society people would attend, and sometimes the audience would be entirely working class.

Audiences had no downtime

Exactly what a person would see when they went to a vaudeville show was different at every theater, but it's highly unlikely that they would be bored. Everything about vaudeville shows was designed to keep audiences engaged.

The show ran nonstop, so there was never even a second when someone in the audience would have nothing going on to entertain them. As noted in "No Applause — Just Throw Money," this approach was partially employed to help theaters make more money. Most theaters only had a play or concert being performed for a few hours and sat empty for the rest of the day, but vaudeville could theoretically never stop.

Each act had an allotted amount of time that they were supposed to be onstage. As one act moved off, another moved on. If there was an act that took some time to set up — such as a magician with elaborate sets — a curtain would come down, blocking the audience from seeing things being moved on and off the stage. Fans didn't just have to wait until they were ready, however. Instead, a performer with no special setup (such as a comedian) would come out in front of the curtain and perform. In this way, the show could continue seamlessly, with the audience always having something to watch while they were in the theater.

Audiences were rowdy

Being at a vaudeville show could sometimes be a chaotic experience, and some got loud and rowdy. Theaters were crowded, and some acts were specifically designed to get audiences riled up, but a rowdy audience could also cause problems.

As explained in "Vaudeville U.S.A.," some audiences seemed intent on destroying the theater, and the fire department would be called in to hose them down. One theater even had an electrified railing around the orchestra pit to stop fans from trying to get onto the stage. Per "Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925," officers were sometimes hired to patrol the gallery and keep the fans in line, and they even carried canes for knocking off peoples' hats if they were making it hard for the people behind them to see.

While many vaudeville shows were reimagined to appeal to families who wanted to see a show, there were some acts that were designed to liven up a crowd and were definitely intended for adults. As described in "Blue Vaudeville," a common act was a skit in which the female performer would change costumes on stage, sometimes incredibly quickly. In one, a woman's clothes are stolen by "a lunatic." In another, a woman changes behind some foliage while "the man in the moon" looks down, becoming increasingly offended by her nudity. Some women performers combined two acts, doing gymnastic stunts or working with wild animals while mostly naked.

There were all kinds of acts

Those who went to see vaudeville could look forward to a wide variety of different acts during the show. As detailed in the Library of Congress, audiences might see acrobats, wild animals, comedians, contortionists, dancers, boxers, stunts, and dramatic scenes and sketches.

Burlesque acts, sometimes called "leg shows" — including those in which women quickly changed onstage — were popular. Some featured sensual dancing, while others were also designed to make audiences laugh with bawdy humor. There were many different types of comedy acts. Some were simply a single comedian telling jokes, while others were sketches, often with a duo consisting of one outrageous person and one "straight man." Others might be parodies of popular songs.

Magicians were also popular stage acts. As described by Time, one magician named Ching Ling Foo was famous for flicking his robe and revealing increasingly improbable items, such as a massive bin filled with milk or a metal container with many live ducks in it. Many acts included animals. Sometimes they were farm animals or common pets trained to do interesting things, like one cat who would scurry up a rope and then drift back down to the stage in a parachute basket. Other times they were wild animals like elephants and bears.

Some acts were more difficult to categorize, such as one man named Sparrow, who would allow people to pelt him with garbage.

Entertainment and education

People who went to vaudeville shows could expect to see some acts reference events they already knew about. While vaudeville was distinct from traditional plays, dramatic scenes and short stories were often performed. While these could be imaginative, flirtatious, or humorous, many were also written to comment on or satirize current events. They specifically referenced issues that audience members would be familiar with.

As stated in the Library of Congress, these short scenes often centered on issues that their audience members might be dealing with in their own lives, such as industrialization and new technology, women's rights, and alcoholism. While the primary goal was always to entertain, some acts were intended to inform as well. As recounted by Time, many early vaudeville performers sang about "the plight of Labour."

By the 1910s, many performers were injecting more of themselves, their personalities, and their views into their acts rather than performing as stereotypical characters. As noted by the New York Public Library, comedians often included political commentary and satire. Prohibition, which made the production and sale of alcohol illegal, was a particularly popular target. Comedians and audiences alike delighted in watching the elaborate codes and rituals that they had to go through to acquire illegal liquor played out on stage.

The show could be almost any length

Vaudeville shows were designed to keep audiences engaged from the minute they sat down, but how long the show actually was varied. As described in "No Applause — Just Throw Money," theaters and their bookers had many strategies for designing an action-packed show, and nailing the right length was a major part of making the event a success. The number of different acts that were performed in any particular show was hard to guess.

As stated in the Library of Congress, there were two major categories of vaudeville: Big-Time and Small-Time. In contrast to the Small-Time rural theaters, Big-Time shows were in popular theaters in major cities. People who went to see a Big-Time show could expect to see eight or nine different acts, though as few as seven or as many as 15 was not unusual. While this was the standard length, there was still plenty of variation. For example, people who attended Small-Time shows might only be shown a single act before running a movie, or they might see more than 20 acts.

Audiences didn't see the whole show

Vaudeville shows were specifically designed to run nonstop without any gaps in the action, so even if the audience had seen every act, there wasn't a natural end to the event. It was entirely possible for an audience member to stay and watch a show multiple times, and because they were exciting, there wasn't usually much incentive for them to leave. After all, the admission cost was the same amount no matter how long a fan stayed in their seat. As described in "No Applause — Just Throw Money," the theaters came up with a strategy for keeping audiences entertained up until the moment they wanted them gone — they planned one bad act.

One act, described as "the chaser," was usually the final one in the show, and it was intentionally boring. Audiences, who had presumably been enjoying the show until the chaser began, would suddenly be subjected to one extremely disappointing act. The vast majority would get up and walk out, clearing the theater for new ticket holders to come in and watch entertaining performances — until the theater decided it was time to clear them out and ran a terrible act to drive them out, as well.

The strategy was very effective. Edwin Milton Royle, a playwright who wrote sketches for vaudeville shows, once estimated that no more than 2% of the audience stayed for more than one full show.

Not all time slots were equal

No two vaudeville shows were exactly alike, but there were some typical elements that people could expect to see if they went to a vaudeville show.

As described in "No Applause — Just Throw Money," many people who went to see these shows would arrive late, so the first act was designed to be enjoyed even if someone missed most of it. Often these acts featured animals or acrobats. The second act was called the "deuce spot" because it was considered the most difficult time to hold the audience's attention. It was usually singing or dancing, but sometimes it was the spot that new performers had to succeed in to be hired by the show. The third — or "flash" act — was a big attention-grabbing one, like a magician. The fourth was usually a comedian or singer performing in front of the curtain, while the fifth act (usually a big act with a popular performer) set up behind it. After that might come dancers, jugglers, a sketch, or a musical number. The second to last spot was reserved for the show's biggest headliner, which was usually a popular singer or comedian. As described in "Vaudeville Old and New," many people attended shows just to see the headliner and would walk out when they were done, leaving the last act to play to a half-empty audience. (The last act was usually "the chaser" anyway, designed to drive the audiences out to make way for new fans.)

There could be audience participation

People in the audience at a vaudeville show were often expected to actively participate in the show. Magicians, in particular, would often call for volunteers from the audience. Magician Howard Thurston, who was at one time more famous than Houdini, frequently brought audience members into the show. One of Thurston's most popular vaudeville acts was a "mind-reading" performance, which required several audience volunteers (per "The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville").

Blanche Ring, an actress and singer who would go on to star in Broadway shows and films, was an influential vaudeville performer. As described in "The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville," many credited Ring with starting the tradition of having the audience sing along when she performed her songs. Some of Ring's performances also encouraged the audience to scream and shout. When she wasn't singing, Ring would sometimes perform "character studies" in which she played characters like maids, manicurists, and telephone operators (generally all Irish). She often encouraged audience members to shout out suggestions for her performances, as many modern improv performers do.

There might be plants in the audience

The term "audience plant" refers to people hired to pretend to be regular audience members despite actually being part of the show. Most people who went to see a vaudeville show wouldn't realize what they were seeing was staged, but they were very likely to see plants.

As described in "Vaudeville old & new," these audience plants were sometimes there to ensure everything went smoothly. When a performer like Blanche Ring called for suggestions, a plant might call out a topic that Ring had already planned to include. Magicians also sometimes hired audience plants to make their illusions more credible. Even up close, the trick looked real to the audience, but in actuality, the plant was in on the performance and would lie for the magician. Sometimes a plant would "volunteer" to be a part of a comedy act and participate in hilarious ways. Often in these situations, it was understood that the real members of the audience would eventually realize the "volunteer" was actually a performer.

While most plants were charged with keeping things running smoothly while maintaining the illusion of audience participation, some were specifically hired to disrupt the acts. These plants were encouraged to heckle comedians, leading to a funny back and forth between the comedian and the apparent audience member. Sometimes they would simply cause chaos, dropping things onto the stage or climbing over seats to make the show more exciting.