Fascinating Flying Reptiles That Existed During The Age Of Dinosaurs

Why can't you hear a pterosaur go to the bathroom? Because the "P" is silent.

At least this dad joke has the virtue of explaining how to pronounce the pterosaur's name. Pterosaurs, that is the flying reptiles of the age of dinosaurs, are one of the most misunderstood prehistoric animals. According to Britannica, pterosaurs dominated the skies during the Mesozoic Era from 252.2 to 66 million years ago. Pterosaurs were, after insects, the first animals to take flight and the first vertebrate to do so.

Pterosaurs are often confused with dinosaurs since they lived at the same time. Yet genetically they are of different lineages. Through evolution, pterosaur ancestors elongated their fourth finger, which was attached to their bodies with a membrane. It would be sort of like if your ring finger grew 10 feet in length. Also, according to the "Princeton Field Guide to Pterosaurs," they may have been covered in a coat of hair-like structures called pycnofibres.

Pterosaurs are usually organized into two major groups. The Rhamphorhynchoid were the pterosaurs who lived from the Triassic to the Late Jurassic periods. These species typically had long tails. From the Late Jurassic to the end of the Cretaceous, the Pterodactyloidea, which had shorter tails, tended to dominate. It is a very general classification with a lot of nuance between the at least 130 different genera of pterosaurs. Let's take a look at some of these fascinating flying reptiles.

Eudimorphodon

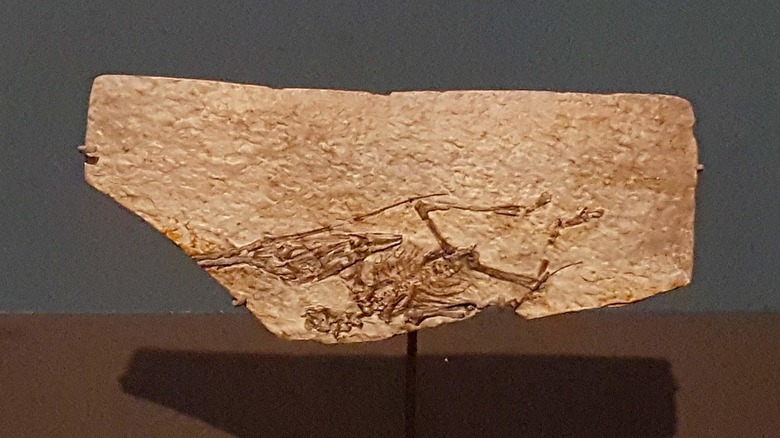

It is unclear exactly when pterosaurs first took flight. As the American Museum of Natural History describes, pterosaur fossils are rare due to the fragile nature of pterosaur bones and also that they did not live in geographic areas conducive to fossil formation. However, there still are considerable fossil findings; the earliest come from the late Triassic and date to well over 200 million years ago.

One of these early pterosaurs was Eudimorphon. According to "Dinosaur!," this animal already had the key traits that made these flying reptiles so successful. This included wings composed of layers of skin reinforced by stiffening fibers. These were filled with blood vessels that brought energizing oxygen to the flight muscles. In addition, there was an elongated snout studded with teeth perfect for seizing fish, and little claws on its wings ideal for hanging. It is likely that Eudimorphon lived near or by water. By its wing size and shape, it is supposed that it often caught its prey while on the wing.

Eudimorphon was not a huge animal, it reached just over a 3-foot wingspan but it was definitely a capable flier. It also had the long tail common in Rhamphorhynchoids but it was more primitive than in later kinds of pterosaurs.

Dimorphodon

Dimorphodon, from the early Jurassic, is a well-known early Pterosaur. Its most notable feature, as explained by Britannica was a large head – and they mean its skull, not its ego. Despite its size, the head did have lots of openings in the skull. This reduced its weight, which would make flight easier.

Like all early pterosaurs, Dimorphodon also had teeth, which, according to "Pterosaurs," were fang-like toward the snout and more serrated in the rear. Dimorphodon probably was not as capable of a flier as later species of pterosaur since it had relatively shorter wings. This could indicate that Dimophodon was a flapper rather than a glider. Still, all the anatomical adjustments needed for flight were fully realized in Dimorphodon including powerful shoulders and very well-developed flight structure in the wing fingers. In addition, the three claws on the wing were very strong, undoubtedly for grasping.

Dimorphodon also differed from later pterosaurs because it had more developed hindlimbs. This has led to some speculation, such as in "Reptiles," that this pterosaur was very much at home on the ground and possibly could have run on its two legs. Without further evidence, thought, this is speculative.

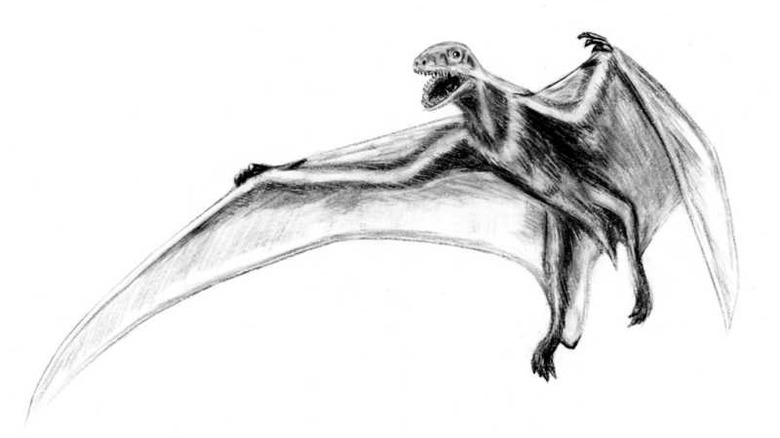

Jeholopterus

Discovered by fossil hunters in 2002, Jeholopterus was a distinct pterosaur from the mid-to-late Jurassic. According to the "Jehol Fossils," this pterosaur had a nearly 3-foot wingspan and a much shorter beak than other pterosaurs. The animal also probably depended on a watery environment since its rear feet were webbed.

Jeholopterus had clear markings of a hairy covering, more so than in other pterosaurs. This has led, as New Scientist reports, to increased debate over the role and nature of pycnofibers. In Jeholopterus, the covering sort of looked more like down on a bird than fur on a mammal. This has led to questions about whether pterosaurs were warm-blooded (endothermic) or cold-blooded (ectothermic), with the assumption being that such a covering would be used for insulation to maintain a constant body temperature. Yet, it seems reasonable when "Vertebrates" suggests that the physical demands of flight plus the insulating coat would make it conclusive that pterosaurs, although called flying reptiles, had a far different metabolism.

Kunpengopterus

What makes the Kunpengopterus stand out from other pterosaurs is that it had a feature that no other pterosaur had – opposable thumbs. Sci News reported that Kunpengopterus lived during the Jurassic period in forests in modern China between 161 and 158 million years ago. As an arboreal dweller, Kunpengopterus was on the smaller side as pterosaurs go, with a 33.5-inch wingspan, and probably developed its opposable thumb to help support this woodland lifestyle. It is notable that opposable thumbs are exceedingly rare in non-mammals and, in fact, Kunpengopterus is the earliest known animal with opposable thumbs. This had led some to dub this new find "monkeydactyl."

Kungpenopterus has also provided some insight into pterosaur dietary behavior. That is, we know they vomited. Smithsonian Magazine reported that fossilized pellets had been found outside their bodies consisting of fish scales. This may indicate that these pterosaurs, like owls, vomited the parts of the meals they couldn't digest as pellets. This would mean that pterosaurs may have had two-part stomachs. Birds are the same way, with one being a gizzard that collects indigestible matter and expels it later.

Rhamphorhynchus

Rhamphorhynchus is one of the more famous of the Pterosaur species. This late Jurassic (159 to 144 million years ago) flier lived in what is now Europe. While only about 20 inches long, it was certainly a capable flier. "The Bare Bones" describes how CT scans of Rhamphorhynchus skull cavities show enlarged cerebellums which are needed for complicated motor coordination, large optic lobes for sharp eyesight, and huge inner ear areas devoted to balance. In addition, the scans showed that Rhamphorhynchus had enlarged regions of the brain that would provide great focus on prey as well as stability on the wing.

One of Rhamphorhynchus' most notable features, according to Britannica, was its long tail tipped with a diamond-shaped structure. The purpose of the tail is unclear to scientists today since most flying animals don't have a tail. It probably served to improve flight by acting as an aerial rudder.

Also, we know a bit about how Rhamphorhynchus lived. It had a long head and interlocking teeth that were perfect for catching fish. In fact, as "The Bare Bones" tells us, fossils of Rhamphorhynchus had fish bones found within them. It is likely that this animal got its meals by skimming the sea for fish, which it trapped with its toothy beak.

Pterodactylus

According to "On the Wing," Pterodactylus (popularly called pterodactyls) was first discovered in the late 1700s in Germany, and described by the scientist Cosimo Collini. Collini puzzled over the elongated forearms of the pterosaur and concluded that it was a sea creature that used its arms to paddle. The famous French anatomist, George Cuvier corrected the error. Other scientists misidentified Pterodactylus as a transitional fossil between birds and bats. After years of sorting it out, scientists finally determined that Pterodactylus is a genus of late Jurassic pterosaurs which included possibly many species. According to Britannica, some may have has a small 20-inch wingspan, with others over three feet. However, there is some debate since it may be that these were all the same species, just at different stages of growth.

All the same, "The Bare Bones" notes that Pterodactylus lived at the same time as Rhamphorychus and was one of the earliest short-tailed Pterodactyloidea. These were small animals and, as "Dragons of the Air" describes, they seem to give the impression of activity, just like small birds.

Tapejara

As pterosaurs developed into the Cretaceous period, natural selection led to some serious bling. Elaborate head crests started appearing which seemingly had no purpose except to look cool. Take for example the genus of pterosaurs called Tapejaridae, which were Pterodactyloidea from 145 million years ago. These creatures, according to "Pterosaurs," "...looked like the devil himself fashioned them using bits of leftover cassowaries after binging on energy drinks."

Tapejara had an enormous, improbable crest on its head that looked like a sail. While some may suppose such a structure was for display, and it may well have been, it also could have served a more practical purpose. "Design and Nature" explains how engineers, while playing around with models of the headcrest, found that it could have acted like a jib on a sailboat. This meant that it could have soared faster than the prevailing wind when its wings were turned upward. The research team wrote, "The basic design of Tapejara is a cross between Weibel (triple-wind surfing boards) and two-masted schooner." This design presumably allowed the pterosaur to soar and swoop with much less effort and greater stability.

Nemicolopterus

If any pterosaur can be called cute, it was the wee Nemicolopterus crypticus, whose fossil was discovered in China in 2008. This early Cretaceous flier had, according to "Dinosaurs and Other Reptiles of the Mesozoic of Mexico," a mere 10-inch wingspan. This would put it at about the same size as a cardinal, although as the New York Times reported, the finding came with one fossil only and it is not entirely clear if the specimen was full grown. Live Science quoted researcher Alexander Kellner of the Department of Geology and Paleontology at the Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro as saying, "The animal is a very young animal, but it's not a hatchling that just left the egg. Therefore it is the smallest pterosaur ever found."

Nemicolopterus, aside from its size, also has other remarkable features. It was one of the first pterosaurs to go toothless. It also had some sort of supporting structures on its femurs which scientists believed would have created powerful legs. It is supposed that because of its size and knowing the historical terrain of that region, this animal was a forest inhabitant, and quickly flitted among the trees hunting for insects.

Tupuxuara

If any pterosaur could win the contest for most elegant headgear it would be Tupuxuara. As detailed by "The Princeton Field Guide to Pterosaurs," this large creature (it weighed about 55 pounds with a 15-foot wingspan), had a crest that swooped back into a sweeping mohawk. This crest was filled with blood vessels which has led books like "Bone Collection" to contend that the crest may have been brightly, even gaudily colored. Some scientists have maintained that these blood vessels served a thermoregulation role, particularly since the head and beak would tend to lose heat faster than other regions of the body.

Paleontologists have also found evidence in Tupuxuara of how the crest changes over time. "Pterosaurs" explains how different fossil specimens of Tupuxuara show not only how the crest grew with age but how they were different for males and females. In males, it was a flatter top, while in females it was rounder.

Pterodaustro

Pterodaustro guinazui was the flamingo of the early Cretaceous. The American Museum of Natural History summarizes how this Argentinian pterosaur had an upturned beak filled with approximately 1,000 long, needle-like teeth on its lower bill. What would Pterodaustro do with such a mouth? Scientists believe it was used to filter feed like a flamingo. It would scoop up water and strain it using its teeth, picking up edible small animals. Flamingos feast this way on a diet of brine shrimp and other small aquatic microlife. While Pterodautro was larger than a flamingo with an 8-foot wingspan, there is no reason to believe that it would have behaved differently.

Research published by the Royal Society Open Science points out how this is evidence of just how diverse and successful a group the pterosaurs were. Aside from demonstrating the flexibility of this unique class of animals, they are also intriguing to the imagination. Brine shrimp, a staple of the flamingo diet, often survive on Spirulina algae that produce carotenoids, which then impart the pink color to the bird. If Pterodaustro had the same diet, perhaps it was a vivid shade of pink.

Dsungaripterus

Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but most beholders would say that Dsungaripterus is the ugliest pterosaur of not just the early Cretaceous, but all of the Mesozoic. "Pterosaurs: Flying Contemporaries of the Dinosaurs" describes Dsungaripterus as having squat, chunky teeth that stuck out of its upturned beak. Its beady eyes were much too small for its skull, which lent it a sinister look not unlike a vulture, but a touch more prehistoric. It was also large. "Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems" reports that Dsungaripterus had a maximum wingspan of over 16 feet.

It is believed that Dsungaripterus feasted on shelled seafood, particularly bivalves such as our modern mussels. This is concluded by examining the blunt teeth that, unlike any other pterosaur, increase in size as you go backward in the jaw. This would allow more crushing ability in the rear of the jaw – for example, a nutcracker cracks nuts more easily at the innermost angle of the tool. Still, there are some questions, since although in the rear of Dsungaripterus's bottom jaw there are teeth, there are none in the upper. It is supposed that this feature was used to somehow manipulate its prey deep in the beak.

Nyctosaurus

Nyctosaurus, a late Cretaceous pterosaur, was one of the most unique, but it was not because of its size. "A Concise Dictionary of Paleontology" tells us that Nyctosaurus was rather small for a pterosaur with a 7-foot wingspan. What made the difference was the head, or at least what was on top of it.

"Pterosaurs: Flying Contemporaries of the Dinosaurs" explains how Nyctosaurus's head crest was shaped like an L-shaped set of antlers that grew up to 2 feet long. Even compared to the headgear of other blingy pterosaurs, Nyctosaurus stands out. Some scientists have speculated that there may have been a membrane on the crest but there has been no fossil evidence to support it. Nyctosaurus apparently grew these crests as they got older, so only the adults had them.

While Nyctosaurus's crest gets all the attention, this pterosaur was also a flier par excellence. As Scientific American describes, the wings evolved to be super efficient, making this pterosaur probably the most efficient soarer of the flying reptiles.

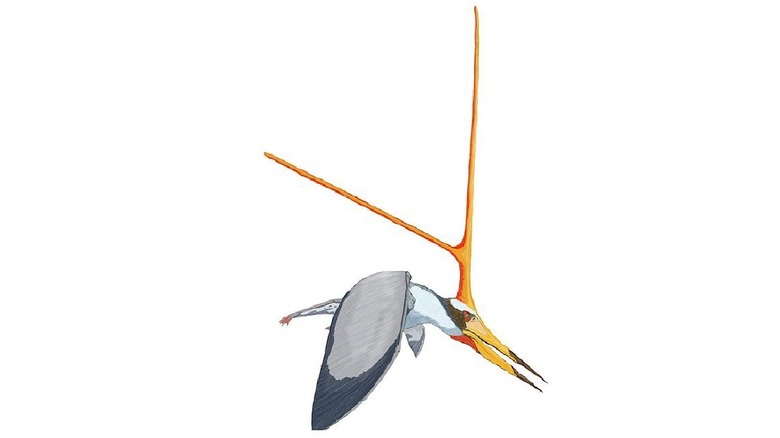

Quetzalcoatlus

Quetzalcoatlus is best described as a flying giraffe. This late Cretaceous pterosaur, according to National Geographic, had a 40-foot wingspan with an over 8-foot-long beak. For some context, its wingspan was longer than an F-16 fighter jet. With these impressive stats, there is a certain awkwardness to Quetzalcoatlus. Smithsonian Magazine explains how it seemed to rest on spindly legs coupled with a gangly body. It had a long, snakelike neck that seems to give it an air of fragility. Ever since the discovery of its fossils in the mid-20th century, scientists have speculated how such a creature could ever get itself off the ground. Did it run and flap? Did it hurl itself off of cliffs and glide?

The answer is found in its powerful leg muscles. Unbelievably, this huge beast launched itself at least 8 feet into the air with a single bound. This space provided enough room for Quetzalcoatlus to engage its tremendous flight muscles and become airborne. It is likely that Quetzalcoatlus lived in forest environments but hunted in freshwater. Scientists think they may have been like ridiculously large herons who also have long necks and stabbing bills that wade through water. Since Quetzalcoatlus is a genus, there were several species. While the largest ones were probably solitary, the smaller ones (only a 20-foot wingspan) did flock with several dozen individuals.

Pteranodon

Pteranodon is one of a select number of pterosaurs that are well known to the general public. According to the American Museum of Natural History, Pteranodon fossils were first found in Kansas in 1871 by the famous fossil hunter Othniel Charles Marsh. This Cretaceous flier made one of its earliest pop culture appearances being cheesily torn apart by King Kong in the immortal 1933 movie. Pteranodon, since then, has become one of the most recognizable pterosaurs.

As described by Britannica, Pteranodon was large, with a 23-foot wingspan, and toothless. In fact, a glance at Pteranodon makes you think of a weird mutant pelican. Its most distinguishing characteristic is the swooped back crest. It is believed that this was used mostly for species recognition although crests were larger in males than females.

While Pteranodon was indeed discovered at the heart of the North American continent, this animal was oceanic. During the Cretaceous, most of the center of the modern United States was covered by a seaway. It is likely that Pteranodon spent most of its time soaring over this inland sea, landing in the water only occasionally to eat or to rest. Considering the size of the animal, it is astounding that it was able to take off and land on water, which probably required a tremendous amount of force to get lift so it could hop and jump until being able to take off.