The Tragic Story Of The Duffy's Cut Railroad Workers Massacre

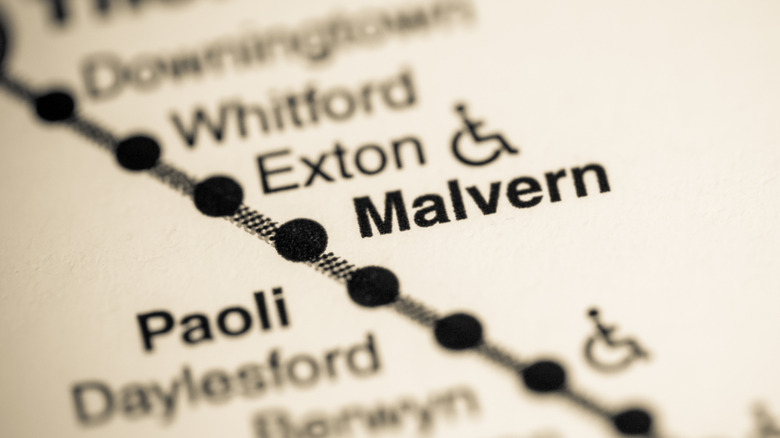

Just 30 miles or so west of Philadelphia, one of America's largest and oldest cities, is the site of a grisly massacre that culminated with victims — as many as 57 Irish immigrants, per Smithsonian — being thrown in a mass grave. It wasn't until a mass grave was found and excavated that a true picture of what unfolded started to take shape. According to Hidden City, the site of the mass grave sits between the towns of Malvern and Fraser along what is currently a track operated by the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority, or SEPTA's, R5 line, which carries commuters between Philadelphia and its suburbs.

The victims of this crime had arrived in America to find work and were quickly recruited by a man tasked with building a stretch of the Pennsylvania Rail Road. It's a crime that illustrates the immense xenophobia faced by Irish immigrants in the 19th century and the lengths to which those in need were willing to go for work.

The Pennsylvania & Columbia Railway

In the early 1830s railroads could be, and probably were, described as new-fangled. Of course, they didn't just appear overnight; they had to be built. It was difficult, laborious, sometimes dangerous work that often wound up being handled by people who had just recently immigrated to the United States.

According to Smithsonian, in 1832, work was being done on a railroad that was going to connect Philadelphia, which to this day is an important port city, to Columbia, Pennsylvania, which sits on the eastern bank of the Susquehanna River. This stretch was so early in the history of railroads that it wasn't being built for locomotives, it was being built for horse-drawn trains.

According to The Lower Merion Historical Society, the 82-mile-long main line of the Philadelphia & Columbia Railway, as it was called, was the first in the world to be built by the government, as previous railroads to that point had been built by private companies. As such, the work was divided up and sold off to contractors. One of those contractors was Philip Duffy.

Duffy and the dangers of Mile 59

Philp Duffy was a contractor who managed to get his hands on a deal to build one of the most expensive pieces of the Philadelphia & Columbia Railway: Mile 59. Of course, this mile of the track didn't carry such a hefty payout because it was going to be easy to build. In fact, according to Hidden City, Mile 59 was the most difficult portion of the track to build because it required cutting through limestone between the towns of Paoli and Frazer. This type of work was so difficult that finding workers willing to do it was a tall order. Slave owners were even unwilling to let their enslaved people do the work.

Due to this stretch being built by Philip Duffy and the important step of cutting through limestone, it became known as Duffy's cut. Duffy was an Ireland native, and he used that to secure a group of men who were willing to work.

The Irish Arrive

Unfortunately, according to Hidden City, Irish Catholics were at the bottom of the socioeconomic pecking order in 1830s Philadelphia, especially if they weren't coming from wealthy or middle-class families who had been in the United States already. Philip Duffy was a middle-class Irishman, and he had used Irish workers on previous projects. In 1929, a newspaper had written an article about another railroad project Duffy had built, and it described his group of workers as "a sturdy looking band of the sons of Erin" (via Smithsonian).

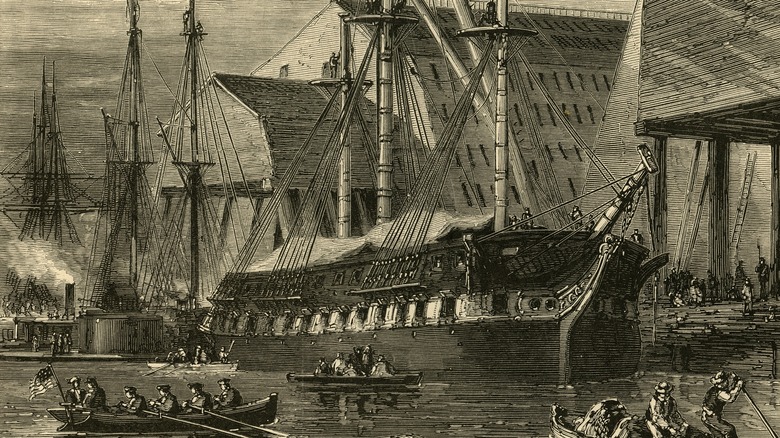

The workers who would labor on Duffy's Cut sailed from Ireland aboard a ship called John Stamp. It took the 57 men and two women on the ship three months to sail across the Atlantic, but they finally arrived in Philadelphia in June 1832. The men on the ship were looking for work, and lucky for them — though it wouldn't be lucky in the long run — they met Philip Duffy on the docks and were quickly hired to work on Duffy's Cut.

The work was being done during a cholera outbreak

When Duffy's crew of Irish immigrants arrived in Philadelphia, it was in the middle of a worldwide cholera outbreak. For this reason, before their ship, John Stamp, was permitted to dock in Philadelphia, it was required to stop at a quarantine hospital down the Delaware River called the Lazaretto. There, a doctor climbed on board to check the new arrivals for cholera.

"If anyone was sick, they would've been off-loaded. No one on the John Stamp had cholera. Everybody was cleared, and the ship went onto port," according to Dr. William Watson, a history professor at Immaculata University (per Hidden City). Dr. Watson pointed out that the Irish were blamed for actually bringing cholera to the United States, and specifically for the outbreak in Pennsylvania. "They did not have it on that particular ship. Cholera came in from Canada down the Hudson River to New York and then to Pennsylvania."

The crew arrives at Duffy's Cut

Duffy brought his workers to where they would be working and they set up a camp near the town of Malvern. As this was in the sweltering heat of the Pennsylvania summer, the Irish workers would've simply walked over to a nearby stream and guzzled down what they thought was some fresh stream water. It's now believed that the streams were likely contaminated and this led to some of the workers catching cholera (via Hidden City). With cholera — a disease that causes extreme diarrhea, vomiting, cramps, and potentially death, especially back in the 1830s — very much at the forefront of people's minds, the locals around where the Irish workers had been camping started to panic.

Eventually, word of what was happening west of the city made it back to Philadelphia, and four Sisters of Charity went to provide assistance. According to The Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, the nuns were serving as nurses during the cholera outbreak. However, when they got there, the locals were already riled up, and the nuns were met with a less-than-warm welcome. They received anti-Catholic sentiments plus fears that they were also cholera carriers, like the Irish workers. The nuns had to turn around and walk back to Philadelphia, some 30 miles, in the summer heat.

The massacre

In truth, it's not known for sure what happened to the 57 Irish Catholic men who made up the crew that was working on Duffy's Cut. While it's likely that some of the men died because of cholera, it appears that others were murdered.

One version of the story posits that in addition to the fears surrounding the cholera outbreak, anti-Irish Catholic xenophobia may have played a part, as some felt that Irish immigrants' willingness to take on work at ta much lower price was taking jobs from locals. It's believed that a vigilante group comprised of individuals connected to the Pratt family, who owned the stretch of track the workers were building, and their company, the East Whiteland Horse Company, went to the Irish encampment and murdered some of the workers by some combination of axes and gunshots (via Hidden City).

Another indication that something nefarious occurred was that, according to Smithsonian, newspapers at the time were known to keep detailed tallies of cholera fatalities. However, they only seemed to note that a few of the men at Duffy's Cut had succumbed to the disease. Duffy tried to keep this atrocity quiet, not out of fear that it would be a blight on the city or the railway, but because he was scared that if the story got out it would prevent him from finishing construction on the lucrative stretch of railway. It must have worked, because he managed to hire another team of Irish workers to complete Mile 59.

Ghost sightings were reported in the years that followed

In 2000, Dr. William Watson and a friend saw something strange on the campus of Immaculata University, not too far from the site of the massacre. "It looked like neon lights in the shape of men. I thought it was something to do with an art show," Watson told Hidden City. "We went outside to the lawn to see them, but they were gone. Nothing was there that could have caused it. It was Hollywood-type special effects. I've never seen anything before or since like that." Two years after this sighting, Watson cracked open a file and learned he wasn't the only one to have experiences like that.

The Duffy's Cut massacre was something that was talked about in hushed tones and whispers for the next 170 years or so. Two years after William Watson's ghost sighting, Dr. Watson and his twin brother, Reverend Dr. Frank Watson, were going through their grandfather's papers when they found a file on the massacre.

The file revealed other sightings, including one that happened in 1832, just about one month after the men died. A man walking along the then still-under-construction tracks was quoted as saying, "I trudged up between the stone blocks until I got on the fill and there I saw with my own eyes the ghosts of the Irishmen who had died with the cholera a month ago dancing around the big trench where they were buried. It's true, Mister. It was awful."

The discovery of the mass grave

According to Hidden City, the file had been put together by Martin Clement, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1935 to 1949. He had been hearing talk of what happened at Duffy's Cut in the early 19th century. The Pennsylvania Railroad even did an investigation into the matter, and much of the information it uncovered was in the file.

Intrigued by this file and the story of the massacre, the Watson brothers searched the area where it reportedly occurred for years until they finally started to recover human remains. One set of remains, recovered in 2009, is thought to those of 18-year-old John Ruddy. According to Smithsonian, the Watsons came to this conclusion because the plates making up the skull they recovered hadn't fully fused. Additionally, the man was found to have a rare genetic disorder that caused him to never grow a right front molar.

This discovery and the story of what happened at Duffy's Cut were covered by news outlets in Ireland, and eventually, the Watsons were contacted by people with the last name Ruddy, some of whom had people in their family with the same genetic disorder as the one found in the body recovered from the mass grave.