The Science Behind Transplanted Organ Rejection

Of the many marvels of modern science, perhaps one of the most impressive is organ transplantation. During a transplant, an organ is removed from a healthy donor and transferred to someone else. Usually, the recipient has a weak or failing organ, either due to an illness like a genetic condition or due to an injury, according to Better Health.

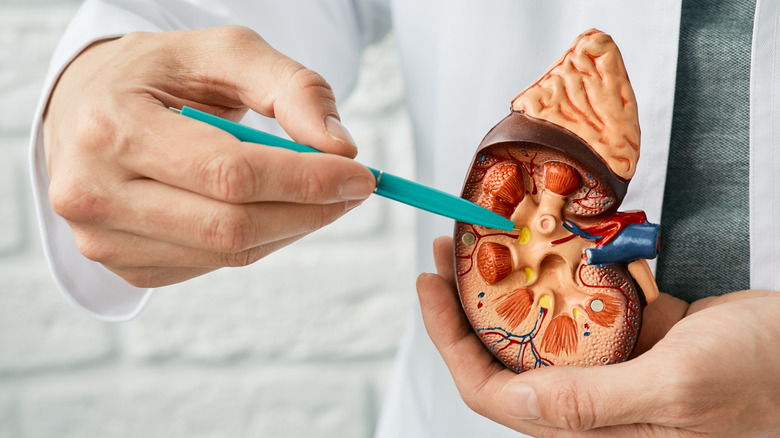

The term "organ transplant" can be used broadly, and can include the transplantation of major organs like the heart, liver, or kidneys, or the transplantation of tissues such as the skin, bone marrow, and corneas, according to Medline Plus. As medicine continues to advance, more and more organs and tissues have been successfully transplanted, including the hands and face, though these remain rare and difficult transplants, according to the Health Resources & Services Administration.

Organ transplantation is considered to be a complex, major surgery, according to WebMD. But even if the surgeon completes the initial surgery successfully, that's not a guarantee that the patient will have a positive outcome. Sometimes, months or years after their transplant, a patient can reject their organ, putting them back on the transplant list, per UVA Health.

The history of organ transplantation

The first successful "organ" transplant was actually the transplantation of skin. In 1869, surgeon Jacques-Louis Reverdin successfully transplanted skin between two patients, according to LifeCenter. Then, later, in 1906, a cornea was successfully transplanted. Though these transplants may not seem as flashy as larger organ transplants, they served as important precursors to later life-saving transplants.

The first successful organ transplant took place in 1954 in Boston, Massachusetts, according to UNOS. The transplant was made between two identical twin brothers, one of whose kidneys were failing. The surgery was a success, and though the recipient of the kidney died eight years after the transplant, it was for reasons unrelated to the transplant itself. Other successful early organ transplants included the first successful pancreas transplant in 1966; the first successful liver transplant in 1967; the first successful heart transplant in 1968; and the first successful double lung transplant in 1986, according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Where donated organs come from

While many organs are procured from deceased donors, other organs can be donated from living donors, according to Medical News Today. Living donors can donate parts of their pancreas, liver, intestines, or one of their kidneys. Deceased donors can donate all these types of organs, as well as other organs, like the heart or lungs.

Since 1968, an organ-matching system has been used in the United States to match potential organ donors to potential organ transplants, according to UNOS. This system allowed doctors to look beyond their local hospital systems for organs for their patients. Now, instead of each city having its own small pool of potential matches, a single pool of donors and recipients exists across the country. This system means more patients can receive timely transplants.

However, not all recipients are matched to donors via this system. Some organ donations come via direct donation, wherein the donor decides who will receive their organ. Those types of donations are called "directed," As many as 98% of living kidney donors directed their kidney donation to a specific recipient, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. However, there are also a small group of altruistic individuals who choose to give a kidney to a complete stranger in what's called a "non-directed" organ donation. This group was composed of around 1,700 people between 2002 to 2015.

The different types of organ rejection

Whether an organ comes from a living or deceased donor, the recipient faces risks with the transplant, including the risk of death, according to a peer-reviewed paper published by the Wiley Online Library. The recipient also has to worry about complications arising years after their transplant, according to WebMD. All organ transplants carry the risk of organ rejection.

Organ rejection occurs went the body's immune system starts to attack a transplanted organ as a foreign invader, according to Transplant Living. If left untreated, a rejection response can lead to severe illness for the organ recipient, causing them to be put back onto the transplant list. It can also lead to death.

There are two types of organ rejection. Acute rejection occurs within a few months of organ transplantation, according to UVA Health. Alternately, chronic rejection occurs a year or more after the initial transplantation. Acute rejection and chronic rejection result from different factors, and so need to be treated differently.

How transplant rejection is treated

Though the idea of rejecting a transplant can sound disastrous, there are ways for doctors to treat organ rejections. One key way that organ rejection is prevented and treated is through the use of immunosuppressant medications, according to WebMD. As the name suggests, immunosuppressants suppress your body's immune system, preventing it from attacking the donated organ.

Immunosuppressants were first introduced into organ transplantation in 1978, when doctors discovered a drug called Cyclosporine which improved outcomes amongst transplant patients, according to LifeCenter. Now, immunosuppressants are part of the standard regimen for all organ recipients. Unfortunately, the medications aren't 100% effective, meaning organ rejections do still occur.

When a patient begins experiencing acute organ rejection, the first step is often tweaking the medications the patient is receiving, according to UVA Health. For chronic rejection, the treatment plan is more complex. Still, patients can help ensure their own health and success by making sure to be consistent with their medication and keeping an eye out for any negative symptoms that might indicate a change in medication is in order.

New developments in organ transplantation

Transplant science is continually evolving. One way that doctors are looking to expand transplant science is into xenotransplantation, or the transplantation of organs from non-human animals into humans, according to the BBC.

While many people choose to donate their organs, most do not, and there is a shortage of human organs available for those who need them to survive. Every day, 17 people in the U.S. die while waiting for organs, according to LifeSource. Scientists hope that more of those lives could be saved by xenotransplants. Already, work has been done to grow genetically modified pigs' hearts, one of which was transplanted into a man's chest in early 2022, according to The New York Times. The recipient of that organ later died, but hopes remain high that the process will be refined soon.

Other new developments in the field of organ transplantation include efforts to discontinue immunosuppressants, according to the National Institutes of Health. While immunosuppressants are currently essential for all transplant recipients, they also have negative side effects, making transplant recipients more susceptible to infectious diseases, according to WebMD. Doctors are also working to develop stem cell techniques that could help damaged organs to regenerate, instead of requiring the donation and transplantation of someone else's organ.