The New York Slave Rebellions You Never Learned About In School

The legacy of slavery in the United States is one of the darkest aspects of this nation's history. Historians and teachers try as hard as possible to spread awareness and knowledge about the history of slavery in America, but with so much information, it's impossible to teach everyone about everything. Unfortunately, that often means critical events get overshadowed by those deemed bigger or more important.

A great case in point are the undermentioned New York slave rebellions in the 1700s. In both 1712 and 1741, the colony of New York found itself ablaze as racial tensions boiled over. While the actual revolts themselves were relatively brief, they brought consequences that far outlasted the flames. The 1712 New York slave revolt, a fire during which slaves killed several whites, brought increasingly severe slave codes to New York and frightened the white population about the dangers of those they enslaved. Tensions continued to simmer for almost three decades, until they burst into the open again during the summer of 1741. The result of unexplained arson throughout the town, some of the most astonishing court cases in American history took place. Rife with coerced confessions and a judge who also served as lead investigator, the 1741 New York slave conspiracy trials stands out as particularly venomous miscarriages of justice.

These are the New York slave rebellions you never learned about in school.

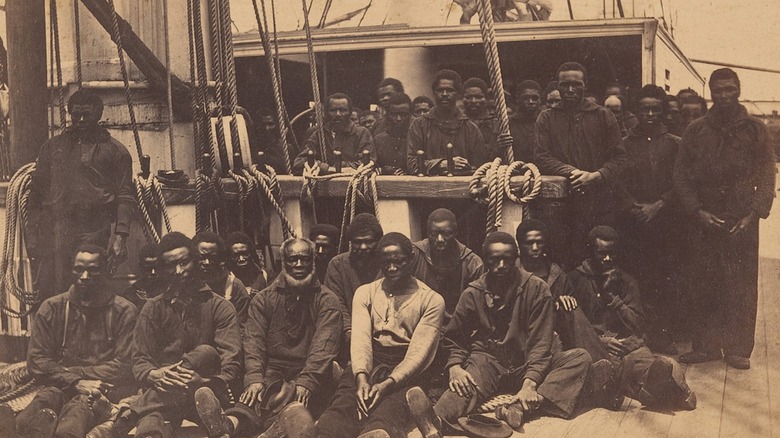

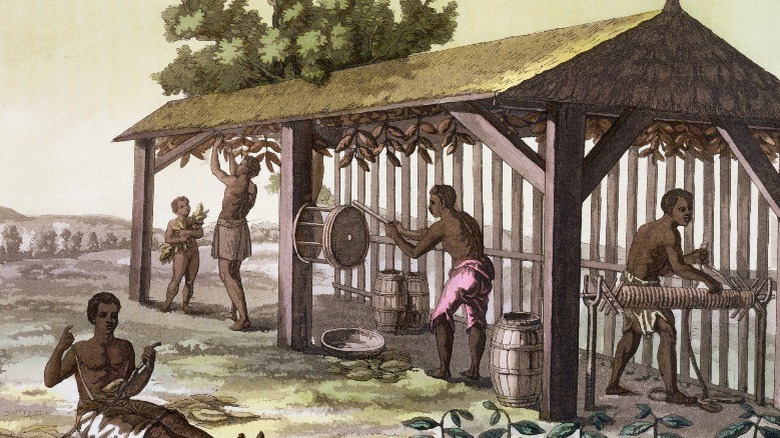

The origins of slavery in New York

According to the New Netherland Institute, New York was originally settled by the Dutch as New Amsterdam in the early 1600s. There were few slaves in New Amsterdam and not a lot of racial tension. Slaves sued and beat whites in several court cases, and some of them were manumitted and given land in the colony. According to the institute, New Amsterdam records did not indicate prominent racial discrimination.

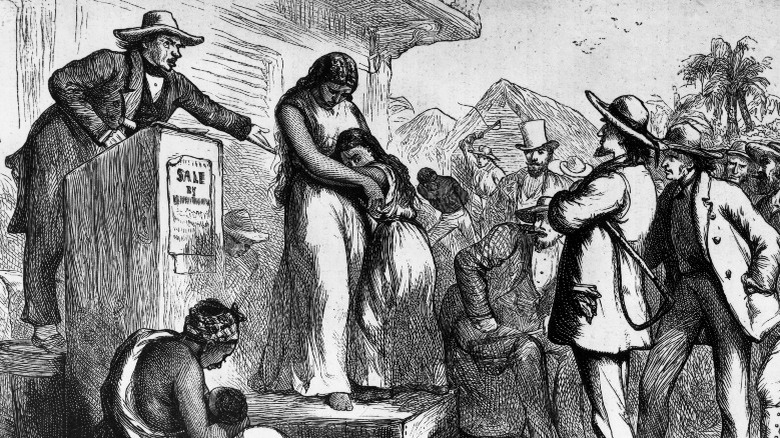

However, in 1664 when the British took control and renamed it New York, they enacted strict slave codes. As shown by the New York Historical Society's fact sheet, slavery vastly expanded under the British, and soon there were more slaves in New York than any other American city besides Charleston, South Carolina. As part of their harsh rule, the British curtailed how slaves could act and even who they could spend time around.

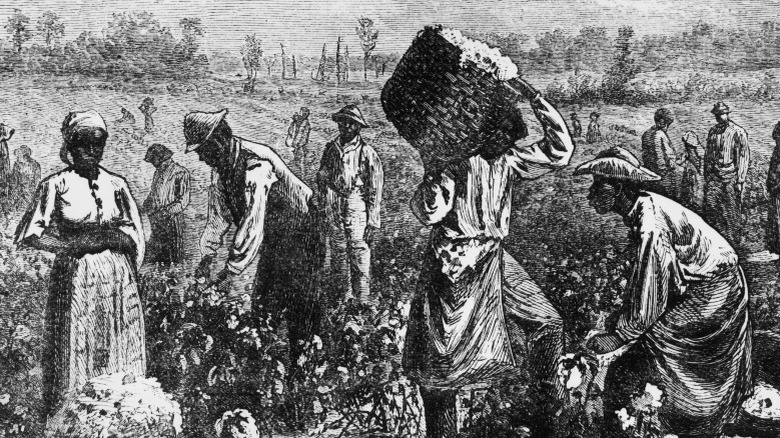

In their book, "Slavery in New York," Ira Berlin and Leslie Harris show how brutal life could be for slaves in 18th-century New York. The female mortality rate was horrific, and the majority of female slaves died by the time they reached 40 years old. Slave marriages were illegal until the early 19th century, in contrast to the New Amsterdam period when interracial marriage was legal and recognized. Despite their often fragmented and fractured lives, family ties were still strong, and most family members actually lived relatively close to each other within the city.

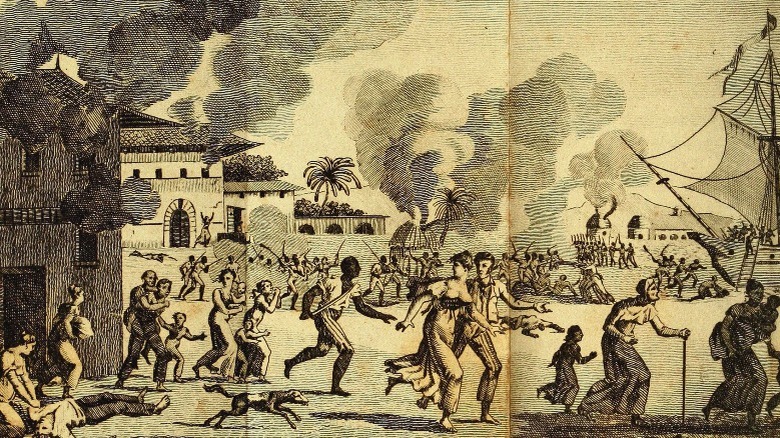

The 1712 New York slave revolt

The 1712 New York slave revolt occurred on April 4 in the outhouse of a banker named Peter Vantilborough. According to "Slavery in New York," the plot began in late March when a group of New York slaves devised a plan to inflame the city and murder whites. They then met on the night of April 6 as part of a group of more than 25 slaves, and they set fire to Peter Vantilborough's outhouse, which quickly brought the attention of numerous whites in the area. The slaves killed nine of them and wounded six more with gun shots and stabbings. One slave stabbed his former owner in the back, and another killed his former owner's son. They quickly fled the area into the woods, and the Governor, Robert Hunter, sent the New York militia after them. The militia rounded up most of the arsonists except for six who committed suicide rather than being taken alive.

In an account from 1893, John Tyler Headley writes that many other slaves joined the group after the fire had started, and all of them rushed together to the woods to escape. The militia was unable to follow them through the thickets, so they waited until morning when they took them prisoner.

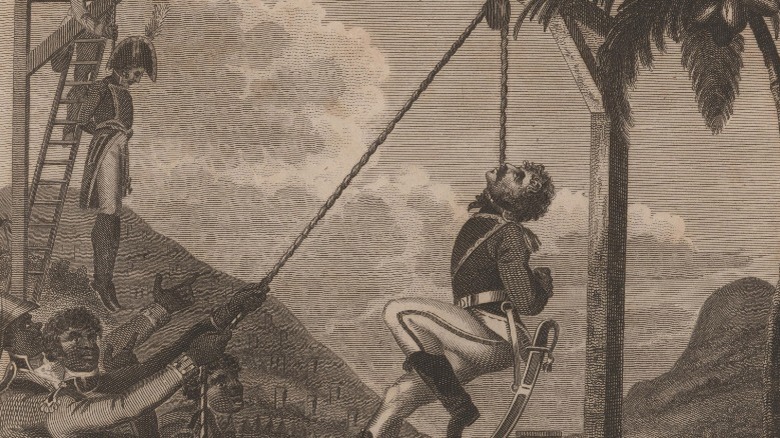

Over 20 slaves were sentenced to death, including a pregnant woman

In a letter from Governor Robert Hunter to the British Lords of Trade written a few months after the revolt, Hunter stated that 21 slaves had been executed. He matter-of-factly wrote that "some were burnt others hanged, one broke on the wheele [sic], and one hung a live [sic] in chains in the town." One slave, whom he referred to as Mars, was tried and acquitted several times as authorities wanted to find him guilty. The governor suggested the successive trials were partially ordered as the result of vindictive slave owners. He gave Mars a reprieve until he could confer with the British Crown.

According to PBS, 21 slaves were ultimately executed. In a shocking turn, one of the accused was a pregnant slave, named either Abigail or Sarah (per CUNY). Mercifully, her execution was suspended, but only until she gave birth, after which she was hanged. Two of the slaves were burned to death, one of them apparently slower than the other, and the slave broken on the wheel was named Claus. The militia initially rounded up hundreds of slaves, but only 21 of them were ultimately convicted.

The revolt brought more restrictive slave codes to New York

The most enduring legacy of the 1712 slave revolt was the city's brutal response. New York immediately passed a wave of more repressive slave codes designed to punish the Black community, both free and enslaved. According to the New York Historical Society's slavery fact sheet, the British created the "Black Code" in response to the revolt. The code prohibited slaves from possessing firearms, passing their inheritance on to their kids, and enacted a £200 bond that owners had to pay before freeing their slaves.

As part of the Black Code, the New York Assembly passed an act which stated that any slave found guilty of crimes like rape and murder would be put to death (per "New York Burning"). The codes also restricted the free Black population, too. The small population of freedmen in the city were not allowed to own any kind of housing or land, and just like slaves, they could not inherit their parent's property.

In 1713, the Codes prohibited slaves over 14 years of age from being out past dark without a lantern, and by the 1730s slaves could be whipped for riding a horse too fast. In 1730, New York enacted a law that prohibited more than three slaves from meeting together at a time, and punishment could be as severe as 40 lashings per offense. They also made it lawful for slave owners to punish their slaves however they saw fit.

The governor of New York thought the executions and new slave codes were excessive

Governor Robert Hunter's letter to the British Lords of Trade a few months after the fire called the events a conspiracy. He suggested the fires were set by slaves who wanted to get back at their owners for working them incredibly hard. He also noted that the number of executions seemed excessive, even when compared to areas with incredibly severe slave codes, and he questioned some of the evidence. Hunter was able to reprieve five from executions, and he asked the Lords of Trade to get the Queen to pardon them.

"Slavery in New York" notes how much Hunter abhorred the executions. In another letter to the Lords of Trade months after his first, Hunter apologized for the brutality of the newly passed slave laws, including the 1712 Black Code. Even the queen found New York's slave codes excessively severe. The queen had previously overruled other harsh slave codes in New Jersey that were modeled on New York laws, including one that mandated castration as punishment for having sex with a white woman (via "Slavery in New York").

Some of the conspirators may have been freemen who were illegally sold into slavery

In another cruel twist, in his letter to the Lords of Trade, Robert Hunter expressed concern that some of the slaves involved may have actually been freedmen. Half a decade before the attacks, a private slaver had brought a group of slaves to New York, some of them Spanish, and sold them all at the market. However, doubt was raised about at least two of the slaves, who claimed they were actually freemen and subjects to the King of Spain. The private slaver had been able to claim they were slaves simply based on the complexion of their skin color.

In his letter, Hunter claimed he felt sorry for the slaves, but he was unable to do anything at the time because the only evidence was the testimony of the slaves themselves. However, in an ironic twist, after they were convicted at trial and sentenced to death in 1712, Hunter was able to reprieve them from execution. His letter asked the Lords of Trades to get them a pardon from the Queen of England to save their lives. According to his letter, the two Spanish slaves were named Husea and John, and the latter's owner was Mr. Vantilborough, the man whose outhouse was originally lit on fire.

The 1712 slave revolt partly laid the ground for the 1741 slave conspiracy

The 1712 slave revolt was one in a series of rebellions and uprisings that put the colony of New York on edge prior to the 1741 conspiracy. According to Famous Trials, there were six separate slave revolts from 1663-1739 in North America, three of which took place within the mainland colonies. In Virginia and Antigua, authorities caught on to the revolts before they took place and enacted harsh reprisals on the alleged plotters, but in several other cases the revolts were bloody affairs that involved dozens of killings and deaths.

In the largest and most violent uprising in 1739, just two years before the New York conspiracy, as many as 100 Black people participated in a revolt known as the Stono Rebellion in the colony of South Carolina (per the New York Times). The rebellion started when a group of slaves killed a pair of shopkeepers and armed themselves in an attempt to make it down to Spanish Florida, where they were promised freedom.

For New Yorkers, all of these rebellions, especially the 1712 revolt which occurred in their own town, worried them and created an atmosphere of distrust and suspicion. According to PBS, white townspeople started to anticipate another insurrection in the near future. In addition, during their trials in New York for the 1741 fires, many slaves pointed to the strict slave codes as reasons for their uprising (per Famous Trials).

The 1741 New York fires

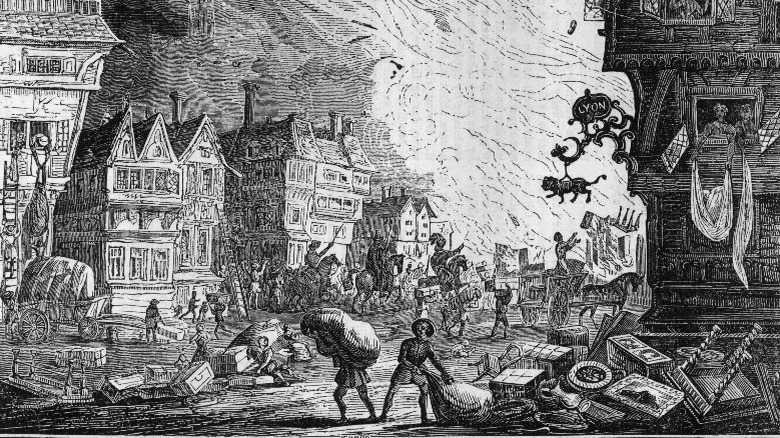

On March 18, 1741, almost exactly 29 years after the 1712 revolt, New York once again mysteriously caught fire. Jill Lepore details the events in her 2005 book "New York Burning." The March 18 fire occurred at the mansion of the New York's lieutenant governor, George Clarke, and townspeople quickly worked to put out the blaze with buckets of water. Soldiers had to rescue the family from the flames and put their belongings in the snow to stop them from continuing to burn, and the wind made people fear the fire was going to spread. The mansion was located inside Fort George, which was made of stone, but the mansion itself was built from wood and was therefore much more susceptible to fire.

Another fire occurred exactly a week later, but this one was put out before there was much damage. Then, for a third successive Wednesday, another fire broke out, and Dutch blockmaker Winant Van Zant's house was completely torched to the ground. That Saturday, two more fires broke out, and townspeople again responded with buckets to stop the flames. A day later, townspeople found coals near a haystack and speculated it was an attempted arson. Monday saw four more fires, bringing the total to seven within the last week and nine since March 18. It seemed like every couple of hours a new fire was being started, and townspeople had to rush buckets of water from one fire to another throughout the day.

The fires turn into a conspiracy

From the first fire on March 18, suspicions started to arise that slaves had been behind the incidents. "New York Burning" notes that while the townspeople were putting out the fire at George Clarke's house, a slave named Cuffee was seen dancing joyfully out front. The Saturday fires brought the first evidence of arson, when it was discovered the fire was deliberately started on a slave's straw bed. The coals found near the haystack on Sunday had left a trail leading to a nearby house, and people suspected the house slave of having attempted to start a fire.

The Monday fires brought even more evidence of arson, and this time, four Spanish slaves were brought in for questioning in connection with one of the fires. In an eerie resemblance to 1712, the supposed ringleader, Juan De la Silva, was a former Spanish suspect who was captured, imprisoned, and sold into slavery in New York, just like John and Husea. At another fire that day, Cuffee was spotted inside a burning house, and he was forcibly taken to jail after a botched escape attempt. The stress of the fires allegedly caused several miscarriages, and by the end of the day New Yorkers were in the street shouting about a slave conspiracy. Soon, authorities started arresting any Black people they found on the streets on suspicion of arson (per Famous Trials).

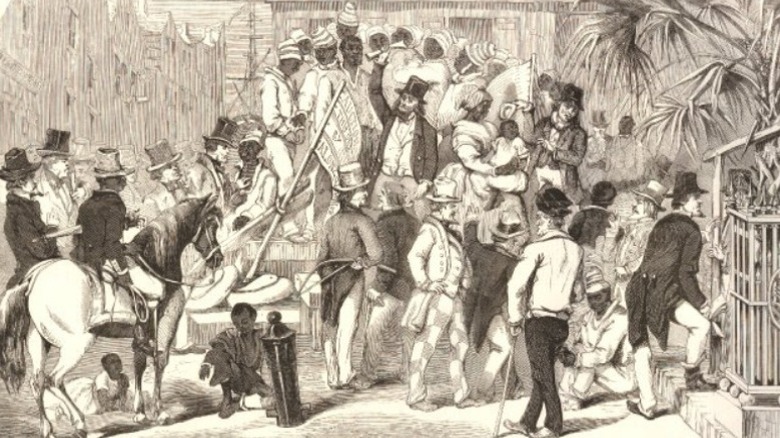

The government paid a white informant to testify about the conspiracy

According to Famous Trials, Grand Jury proceedings began on April 21, just over a month after the first fire was set. Addressing the jury, Justice Frederick Phillipse plainly stated he was going to present evidence of conspiracy to commit treason. The jury immediately summoned Mary Burton, a 16-year-old indentured servant to a local tavern owner. She initially refused to testify, until she was threatened with jail and offered a £100 reward. Once in front of the grand jury, Burton wove a tale that involved robbery, arson, and premeditated murder against whites.

A series of trials started May 1, and authorities used the testimony of another white indentured servant, named Arthur Price, who made further accusations about more slaves being involved in the conspiracy. Once in jail, slaves started to accuse other slaves of being involved, and some were promised immunity in exchange for testimony that implicated others. Some of the accused admitted involvement in the fires, while others denied they had any connection. Convictions swiftly followed.

In addition to slaves, Burton also identified three white conspirators as involved in the plot. They included her master, Peggy Kerry, the owner of the tavern she was indentured to, John Hughson, and Hughson's wife. The presiding judge for their trial pushed the jury towards a guilty verdict, which they promptly delivered for all four defendants (Hughson's daughter was also tried and convicted).

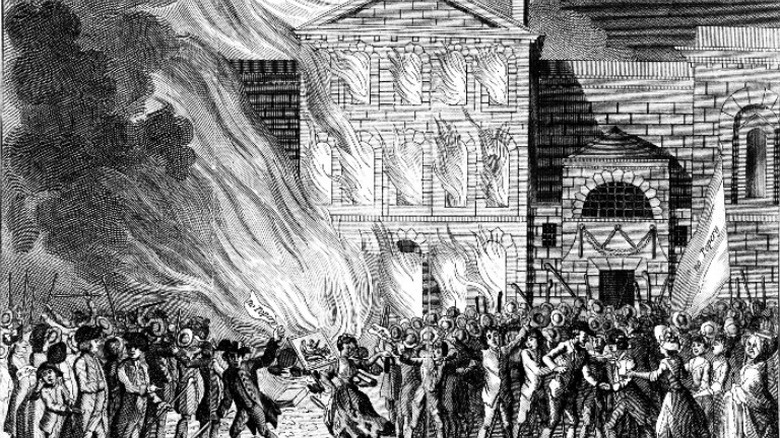

The trials were completely rigged from the beginning to create the conspiracy

Historians have long considered the 1741 conspiracy trials some of the most rigged and biased in American history, and many observers were even uncomfortable with how it proceeded. In his 19th-century book "Bryant's Popular History of the United States," William Cullen Bryant claimed the trial ignored "all rules of legal evidence ... was without precedence, and has had no parallel in any civilized community." Immediately after the trial, the presiding judge, Daniel Horsmanden, complained that people doubted the trial's veracity (per Famous Trials). The complaints were fueled by witnesses who later recanted their statements and the realization that Burton had repeatedly lied during her testimony.

A critic of the trials also wrote an anonymous letter to authorities, which compared them with the much maligned Salem Witch Trials the century before. The letter also expressed severe doubt about the conspiracy in general, and suggested those responsible for it would face punishment in the afterlife.

The justices presiding over the trial went to lengths to suggest the proceedings were not racially motivated, claiming the slaves were treated "in the same manner as any white man, guilty of your crimes, would have been" (per Yale University). However, with a judge that also acted as lead investigator, and who questioned suspects without the presence of a lawyer, it's hard to imagine a clearer violation of due process and judicial ethics (per Famous Trials).

The punishments were severe

In all, 30 Black slaves were executed along with four whites (per the University of Missouri-Kansas City). The executions started on May 11, less than a month after the grand jury was initially convened. The first two, Caesar and Prince, were executed by hanging, and Caesar was publicly hung in chains for display. On May 30, two more slaves, Cuffe and Quack, were publicly burned at the stakes even after a stay of execution had been granted. On June 12, both the adult Hughsons and Kerry were hanged, but the daughter was given a brief stay in hopes of obtaining a confession. John Hughson was then ordered to be publicly hung in chains next to Caesar who was still in place.

On June 19, after at least five more slave executions, city officials issued an order granting pardons to any who voluntarily provided a confession of their involvement. 71 slaves confessed within weeks. On August 29, a white priest named John Ury was hanged for his involvement in the conspiracy. The pardoned slaves were not let off without punishment, and most of them were taken from New York to the Caribbean where they were sold again (per "Slavery in New York").

Many of the confessions were likely extracted through torture

Authorities offered many potential rewards for anyone who gave them information about the fires. For slaves, they offered the possibility of manumission or freedom, £20, and a pardon for any involvement (per Famous Trials). However, many slaves also had another compelling reason to confess or share any details: they were being tortured and beaten by authorities hoping to get incriminating statements. According to CUNY, New York official's torture practices served two goals; They got confessions, and they terrified other slaves into confessing before being beaten themselves. Some referred to it as a "reign of terror," and it brought unfavorable comparisons with the Salem Witch Trials.

In "New York Burning," Jill Lepore writes that though there is not physical evidence of torture, there is much circumstantial evidence. Torture and physical violence were a normal practice for dealing with slave revolts during the 18th century, as happened in 1712 in New York and 1736 in Antigua, so Lepore suggests it's likely it was used again here. She also notes that magistrates might not have even considered owner's violence against slaves to have been noteworthy considering the brutality of slavery at the time. According to Lepore, "there is every reason to believe but no way to prove" the existence of torture and coerced confessions.

There is still no definitive answer today whether or not it was a conspiracy

There is still debate today among historians as to the nature and efficacy of a conspiracy plot. According to Professor Douglas O. Linder, there was indeed a plot amongst slaves to set fire to the town, but it likely arose from "a simple desire for liberty." He also noted that the English and Spanish were then currently engaged in a war, and the slaves may have sought an opportunity to aid the Spanish and throw off the yoke of their English oppressors. "New York Burning" argues that though the trial and judge were clearly biased, the plot cannot just be dismissed as the machinations of 18th-century racists. She also argues that though much of the evidence is of questionable veracity; it's the only available evidence, and thus it merits being looked at seriously.

Three centuries later, long after the participants in 18th-century New York revolt and conspiracy have passed, America still grapples with its complicated and tangled history. The definitive truth is likely impossible to find now, with so much time having passed since the events, and the mystery still lives. These were the New York slave rebellions you never learned about in school.