How Junko Tabei Became The First Woman To Make Mountain Climbing History

She didn't look like an adventurer. The gentlemen who scaled Mount Fuji and other Japanese peaks for sport, in the 1950s, didn't know what to think of the young woman climbing alongside them. At 20, she stood 4-foot-9 and seemed to weigh almost nothing. A few of them refused to climb with her outright. Others made rude jokes about her joining the university alpinist club to find a suitable husband.

It didn't matter. Junko Tabei was young, and small, and female. But she was a serious climber, dedicated to mastering Japan's mountains before attacking the great peaks of the world: the Swiss Alps, the Himalayas, all of them. By 1969, according to Adventure Journal, she had founded Japan's first female climbing club. Throughout the next decade she and her teammates successfully climbed the most dangerous, celebrated peaks in the world. By the 1980s, Tabei had reached the top of the Seven Summits, the highest peaks on each of the continents — mountains like Kilimanjaro in Africa, Denali in North America, Aconcagua in South America, and, yes, Everest in Asia.

A love of the mountains

Tabei was born in 1939 as Junko Ishibashi, as Women in History recounts, in Fukushima, Japan. A frail child, she had a revelation at the age of 10 during a class field trip to Mount Nasu, a picturesque mountain popular with hikers (via National Parks of Japan). The view from the top of Nasu (seen above) exhilarated her, and she realized that climbing was a fulfilling, non-competitive activity, the ideal sport for her.

Unfortunately, her passion would have to wait almost 10 years. Tabei had six siblings, and her parents didn't have the money to buy her the ropes, boots, crampons, and other climbing gear. Tabei went on to attend Showa Women's University, where she studied English literature. Alpinism was popular enough among Japanese students that several clubs had sprung up, which organized climbs and hikes. Tabei seized her opportunity. As Adventure Journal recounts, Tabei was frequently the only woman to attend meetings or join these excursions, and while some climbers welcomed her, others clearly resented her.

An exciting time to climb

Tabei's timing could not have been better. Mountaineering, or alpinism — scaling high mountains for its own sake — is relatively new as a sport. The idea is ancient, of course: The Italian poet Petrarch climbed Mount Ventoux in the 14th century, telling a friend that "My only motive was the wish to see what so great an elevation had to offer" (per Fordham University). But no one conceived of it as a sport until the mid-19th century, when Swiss and English climbers like John Whymper began systematically attempting, training for, and writing about climbs in the Alps (via Britannica). These early mountaineers pioneered the use of ropes and other gear, and laid the ground for rock climbing to become a sport in its own right.

This is considered the "golden age" of mountaineering, but the 1950s and '60s — when Tabei was exploring the mountains of Japan — was a kind of silver age. The highest peaks in the Himalayas, including Everest and K2, were first summited between 1950 and 1954. According to The Guardian, rock climbing specialists like Don Whillans were scaling vertical cliff faces long considered impossible. The sport was changing rapidly. What better time to open it to women?

A club for women

Tabei persisted, in spite of the sneers from the men up-rope of her. She had other problems, too. Alpinism is an expensive, time-consuming hobby. The former was a serious problem when she was still a student, but the second became a hurdle later, when she took a job as editor of a science magazine, the Journal of the Physical Society of Japan.

But passion always finds its way. On weekends and holidays, she took on one peak after another up and down Japan, including the celebrated Mount Fuji (see above, with hikers). It wasn't all bad company, either: in 1966, at age 27, she married one of her climbing companions (per Women in History). But the expectation that women would stay home and leave the boys to their adventures was still strong in Japan, and no one seemed willing to challenge it. Tabei wanted to change that. In 1969 she founded Japan's first all-women climbing club, Joshi-Tohan. The club's first foreign expedition came a year later.

The Himalayas

The Joshi-Tohan climbing club's maiden trip was to the base of Annapurna III, in Nepal. As Britannica explains, Annapurna is a massif in the greater Himalaya range, whose four peaks have been numbered in order of height. The highest, Annapurna I, is the 10th highest mountain in the world at 28,150 feet (8,580 meters). Annapurna III isn't far behind, at 24,786 feet (7,555 meters). Annapurna III is a particularly difficult climb; no one managed its southeast ridge until the end of 2021 (via Alpinist).

Tabei and Joshi-Tohan summited successfully, not only the first women on the mountain, but also the first Japanese. Even more impressively, they refused to use one of the established routes, founding a new one on the mountain's south face. The weather at the summit was so cold that the film cracked in their camera, leaving them unable to take photos.

After Annapurna, Tabei took on the greatest challenge of them all: Everest. Joshi-Tohan applied for a permit in 1970. The approval process would take four years.

Everest

Those four years were busy. As Women in History explains, Tabei had to organize a team of 15 expert climbers, all Japanese women, for this most perilous and prestigious of climbs. Curiously, she did not lead this group; that honor fell to Eiko Hisano.

The biggest problem for the 15 explorers was money. The trip was enormously expensive, and although they managed to land a few corporate sponsors, like the newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun and Nippon Television, each climber had to contribute some $5,000 dollars on their own for gear, supplies, and transportation. Tabei's editorial job simply didn't pay enough to cover these costs. She took to giving piano lessons after work and economized around the house, sewing clothes from old tarpaulin and thrown-out curtains.

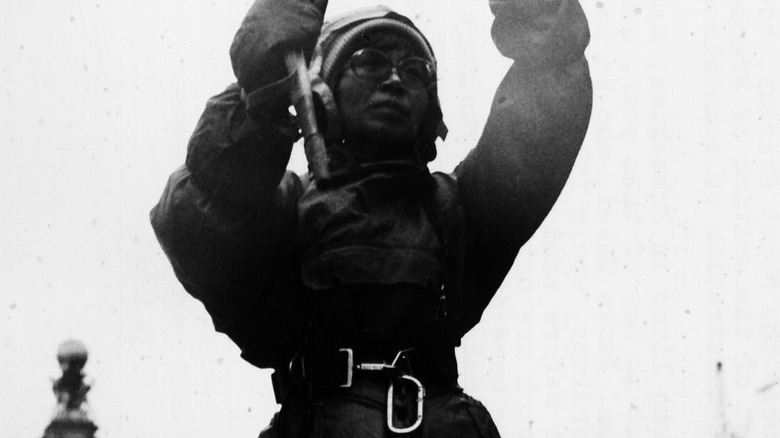

Finally, in May of 1975, the 15 climbers arrived at base camp of the world's biggest mountain. Accompanied by six Sherpa porters, they made good time for two days, but were struck by an avalanche, burying Tabei in snow. She lived, but it took another two days of rest for her to carry on. The team pressed on. As they approached the summit they faced another difficult decision. There was only enough supplemental oxygen for one climber to reach the peak. Who would it be? Hisano, the team leader, gave the tank to Tabei, who successfully planted the Japanese flag on the roof of the world — the first woman, and 36th person, to stand there.

A legend

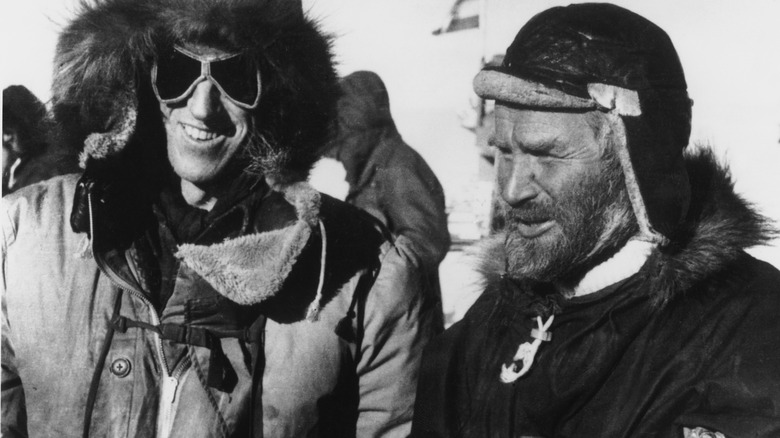

Huge crowds greeted the 15 climbers on their return to Tokyo. They were celebrities, pioneers in women's sport and alpinism alike. Just days after the Japanese ascent, another woman made it to the top, this time a manual laborer from Tibet named Phanthog (per Adventure Journal). But Tabei (seen above with Sir Edmund Hillary) was not one to rest on her laurels. She wanted more expeditions. Through the 1970s and '80s she completed the Seven Peaks challenge, which included a trip to Antarctica; she then tried to bag the highest peak in every country, only giving up around 70. (It's unknown if she attempted Holland's highest point — per World Atlas, the 1,059 foot Vaalserberg.) Later she made "clean-up" climbs with her husband, cleaning the garbage that defiles every mountain where alpinism becomes a tourist attraction.

In 2002, Tabei returned to university to study ecology, becoming an important public voice on mountain conservation in Japan. In 2012 doctors diagnosed her with cancer, and she died four years later, aged 77.