The History Behind The Stolen Caravaggio's Nativity With St. Francis And St. Lawrence

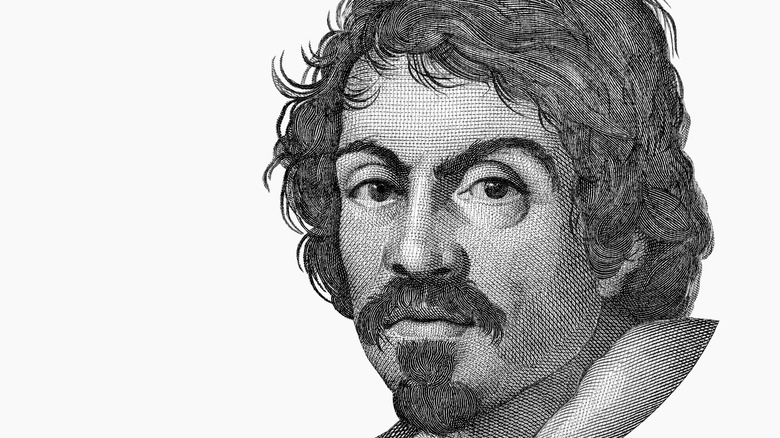

Some of the world's most famous art lives on only in memory — as the original masterpieces disappeared mysteriously long ago. This includes the "Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence," created by the Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio in 1609.

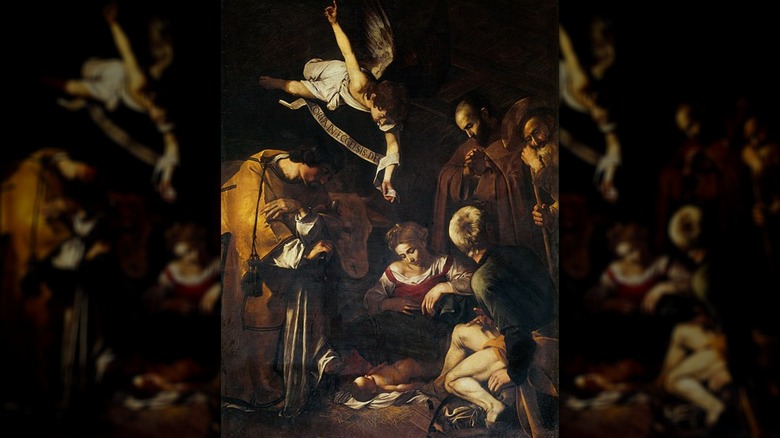

The work depicts Jesus Christ's birth and shows the infant nestled in a haystack on the ground, surrounded by saints and shepherds, a moment scholars say was meant to showcase the simplicity of his station upon entering this world, according to Live Science. The painting disappeared from a Palermo chapel in Sicily's capital, which housed it until Oct. 18, 1969. No one knows who stole the acclaimed art, although rumors point to the Sicilian mafia as the perpetrators of the theft. Visitors can still see Caravaggio's masterpiece, though, since a replica was placed in the chapel in 2015.

So whodunit? The criminal — or criminals — both daring and outrageous, slashed the valued canvas from its frame and left a mystery that lingered for more than 50 years. Caravaggio's painting, also known as "The Adoration," was known for its understatement and symbolism, per Caravaggio.net, and was painted using a chiaroscuro technique that plays with light and shadow.

Despite the subtlety of its portrait, the work towered above the altar at the Oratory of San Lorenzo at almost 9 feet by 6.5 feet before it vanished — a nefarious feat that is still on the FBI's top-10 art crimes list. Whoever solves this puzzle would find a handsome reward since the piece's value is around $20 million.

Where is Caravaggio's painting?

So where is the painting? The answer depends on whom you ask — many theories abound on what happened once the artwork was slashed from its frame. One theory maintains that the canvas's size required several participants to steal it — and that lends credibility to the idea that the La Cosa Nostra or Sicilian Mafia nabbed it. This group, according to Odyssey Traveller, began when clans formed a protective force against foreign invaders. By the 19th century, their activity evolved and the group engaged in crimes like racketeering. Eventually, the Sicilian Mafia grew into an international criminal organization participating in everything from illegal immigration, money laundering, and drug trafficking, said We Are Palermo.

Several Mafioso members have offered their version of what ultimately happened to the "Nativity," offered "The Art Newspaper:" Francesco Marino Mannoia divulged to a judge in 1989, that the painting no longer existed — the intended buyer refused its damaged state and demanded the piece be burned. Another theory is that Gerlando Alberti said he tried to sell the work, but couldn't find a buyer so he buried it — subsequent excavations never discovered the painting. Mafioso Gaspare Spatuzza insisted that Caravaggio's canvas became the prey of mice and pigs that nibbled away at it while stored in a barn, while Salvatore Cangemi claimed he saw the piece displayed at mafia meetings to show off their power. Stories like these provided investigators with false trails for years and tantalized art lovers who believed the painting might resurface.

The kingpin and the painting

While many believe the mafia stole the painting and destroyed it, the case to find Caravaggio's work reinvigorates periodically. In 2017, for example, the Antimafia Commission re-opened the case after receiving updated statements from mafia members Marino Mannoia and Gaetano Grado that pointed to mob boss Gaetano Badalamenti acquiring the painting before cutting it up and shipping the work to Switzerland, reported The Art Newspaper.

Not everyone agreed with this theory, including some antique dealers who believe the painting remains intact. Still, the accusations against Badalamenti weren't new. The oratory's custodian, Monsignor Benedetto Rocco, had pointed to the Mafioso early in the investigation when the painting first disappeared. He had also requested that the building obtain more security prior to the theft, especially after the state broadcasting company, RAI, produced a show, which aired in August 1969, on the treasures the oratory contained.

The exact date of the theft was never actually pinpointed. A congregation viewed the painting during an October 12, 1969 mass, and oratory caretakers reported it missing on October 18. It is possible by the time the police arrived on the scene that the "Nativity" had already left the country.

Lots of theories, but no conclusions

Badalamenti, who died in 2004 and spent 17 years in a U.S. prison for drug trafficking, reportedly showed a Swiss art dealer the painting according to the testimony of mob informant Gaetano Grado to the Antimafia Commission. The expert advised Badalamenti to cut the canvas into pieces to facilitate its sale potential, said The New York Times.

The Commission hopefully embraced the new information. "He's the first turncoat with a direct connection to the theft," Francesco Comparone, the commission's top councilor, told the New York Times. But, not everyone believed Grado's words, including Bernardo Tortorici di Raffadali, president of the cultural association, Amici dei Musei Siciliani, a group that promotes Palermo's art. He explained that the complicated robbery needed several skilled participants, especially since the slicing of Caravaggio's work was managed "without leaving a milligram of paint behind." The theft, to Tortorici di Raffadali, seemed like a commission.

Ludovico Gippetto, president of Extroart, another cultural organization in Palermo, also believes someone else besides the Mafia took the painting. He offered a hypothesis that "a family so powerful that the police couldn't even knock on their door," arranged for the work's disappearance.

The hunt for a masterpiece intensifies

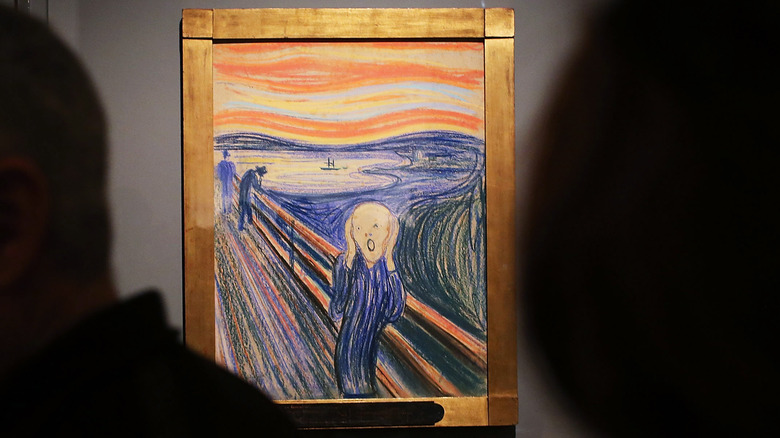

Tortorici di Raffadali admitted that regaining the "Nativity" is only possible through "a kind of miracle" to The Guardian. Charles Hill, the art detective who recovered Edvard Munch's "The Scream" after its theft in 1994 agreed that the theory that placed the "Nativity" in Switzerland was wrong. "You don't just believe a pentito who shoots his mouth off," he said of Grado's admission of guilt that he helped steal the painting before Badalamenti possessed it.

Hill conducted his own investigation, speaking to several informants and he believes the painting is out there somewhere in Sicily. His theory maintains that the mafia used art to bargain during illegal maneuvers. His hypothesis gained credibility in 2016 when two of Van Gogh's works were discovered in a boss's home. Hill suspects that when the last La Cosa Nostra boss, Matteo Messina Denaro, is arrested "Nativity's" location will finally be revealed.

Leoluca Orlando, Palermo's mayor, hopes for the painting's return. "Today this city has changed and is demanding back everything the mafia took away from it," he said in another Guardian article. "Even getting back a small piece of it would be considered a victory."

The art of reproduction

For now, though, art lovers must find satisfaction in the "Nativity" reproduction placed in the space once reserved for Caravaggio's painting in Palermo's Oratory of San Lorenzo. Until 2015, the spot featured an enlarged photo of the masterpiece, according to Lonely Planet.

The TV broadcaster Sky spearheaded the project and hired Factum Arte to produce the piece, said the Guardian. The company has worked on other similar projects, and once even made a duplicate of King Tutankhamun's tomb installed close to the original in Egypt.

The replica used existing photographs of the painting, took digital scans of them and employed a team of restorers to create the new piece. The work provided many challenges, especially since few images of the work remained. One slide, taken by photographer Enzo Brai, only included a portion of the canvas. Still, the group could see the work's brush marks. They also examined the artist's three paintings in Rome's Church of San Luigi dei Francesi for hints on the hues Caravaggio used since some think the works were produced during the same period as "Nativity."

"We are not bringing back the original, but a facsimile. However it is one that will look very similar to the original," said Roberto Pisoni, the head of the Sky Arts production hub, to the "Guardian."