The Silent Film Origin Of The Phrase Cut To The Chase

So many of us have a tendency to tell the longest and most meandering anecdotes. These are the people who, like dear old Abe Simpson, will embark on a retelling of their whole life stories when they were only supposed to be telling us who they met at the grocery store that morning.

In today's high-pressure, super-busy world, many such people will be swiftly told to cut to the chase. This familiar expression, per Merriam-Webster, has come to mean "to get to the point," and it seems to have arrived at that definition by way of the word "cut" (in the sense of "to stop photographing motion pictures," Merriam-Webster helpfully adds).

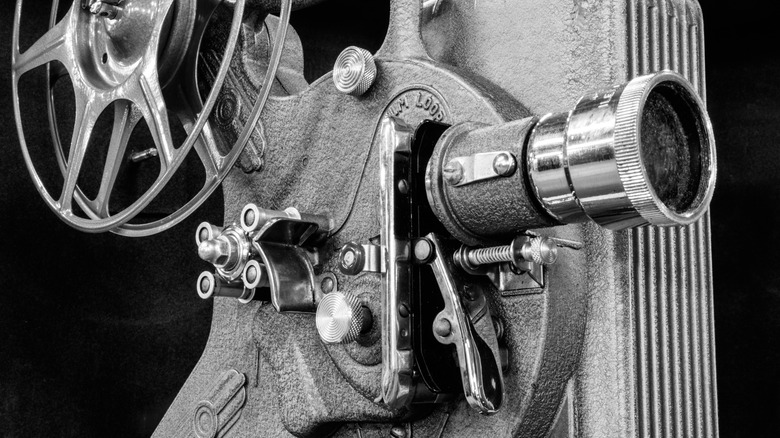

The world of silent films has brought us many iconic moments and memories, such as the shenanigans of Charlie Chaplin (who, per The New Yorker, did not make a talkie until 1940's "The Great Dictator"). Even movie buffs may not know, however, that they also seem to hold the origins of this curious phrase.

When movie viewers only want to see the best bits

According to The Phrase Finder, the term is about as old as silent movies themselves. Such films relied on the physical performances of the actors, and so silly chases, slapstick and other such visual aspects of storytelling were common. The 1929 novel "Hollywood Girl," The Phrase Finder explains, includes a reference to this, in the simple direction: "Jannings escapes ... cut to chase." Author Joseph Patrick McEvoy, however, was referring to a literal chase.

Before the phrase "cut to the chase" adopted the meaning it holds today, a similar term seems to have arisen beside it: "Cut to Hecuba." According to Michael Warwick's 1968 article in "Stage," titled " 'Theatrical Jargon of the Old Days" (via The Phrase Finder), a reference to Hecuba appears in Shakespeare's "Hamlet." As was the playwright's wont, there was an awful lot of talk before Hecuba's name pops up in Act 2. Cutting to Hecuba was, per Warwick, "an artifice employed by many old producers to shorten matinees by cutting out long speeches."

As with the cinema industry today, viewers seek out movies that make them cry, laugh, applaud, and everything in between. They want to be entertained. Like a teacher battling to engage less-than-riveted students, movie-makers get the best results when they can keep their audience interested. How was this achieved? With fewer long, droning speeches. By cutting down on slower-paced moments. By cutting to the chase.

You don't need to cut to a chase to cut to the chase

As Mental Floss reports, a non-literal meaning of the phrase had truly started to catch on by 1955. That year, journalist Frank Scully released "Cross My Heart." In the book, Scully describes his impatience with both teaching and following directions himself. He writes, per the Internet Archive, "I am the sort who wants to 'cut to the chase.' As far as I'm concerned, we can read the instructions later."

This, then, is the essence of what cutting to the chase is all about. Who has time to watch the boring bits of a movie? Why bother reading the instructions, when you can simply muddle along until you figure out what each of the settings on a given device does? Essentially, the meaning of the phrase "cut to the chase" hasn't really shifted very much at all.

Perhaps the most frank early use of the modern term can be attributed to The Berkshire Evening Eagle. In 1947, per The Phrase Finder, the newspaper baldly proclaimed, "Let's cut to the chase. There will be no tax relief this year." There were surely no silly silent movie antics to balm that wound.