The Duties Of A Plague Bearer Were As Gross As You Thought

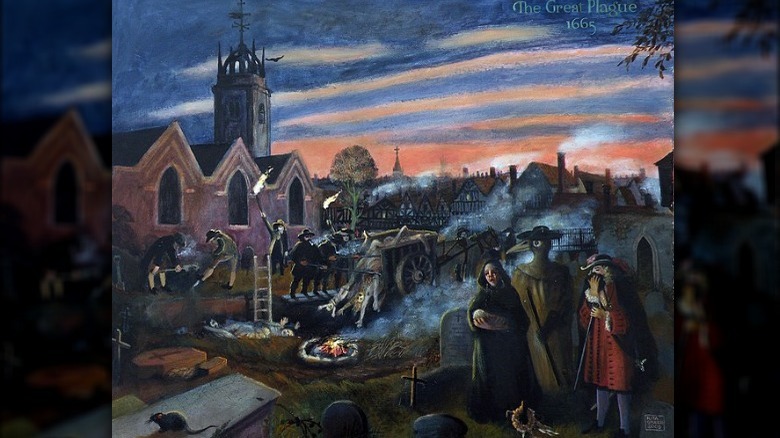

A great plague tore through the city of London in the years 1665 and 1666, as Britannica notes. This was just one of many outbreaks of the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the cause of the bubonic plague, sometimes called the Black Death (via Harvard Medical School). During this time, nearly 70,000 Londoners died. Some put that number closer to 100,000, out of a total population in London of a bit less than 500,000. Nearly half of all London's residents fled the scourge.

Addressing what must have seemed like an unending tidal wave of dead bodies were plague bearers. It was a grim and ghastly profession. Afflicted families, otherwise quarantined, brought out the dead bodies of loved ones who had sometimes remained inside their homes for several days, if not longer. Piled high on carts, those bodies would then be pulled through the streets before they were thrown in mass graves or disposed of wherever space would allow. The job of a plague bearer was clearly one of the worst in all human history.

What was the Black Death?

The first outbreak of the plague known as the Black Death was in mid-14th century Sicily. Prior to that, the disease had wreaked havoc across all of Asia and parts of North Africa. There were deadly results whenever or wherever the bubonic plague took hold of a population. It was likely spread through trading ships. It's believed that similar outbreaks of Black Death had occurred for centuries all over the world. Deadly waves of Black Death or bubonic plague crested over Europe for years, including the Great Plague of London in the mid-1660s. From the outset of the first recorded European eruption of bubonic plague in Sicily, an estimated 20 million Europeans died, or one-third of the continent's population (via History).

By any measure, a Black Death infection was a terrible thing to experience and an even worse way to die. Waging war on the lymphatic system, the first sign of plague infection were most often "plague boils." These sores could be of varying sizes that typically showed up in armpits and groins. Soon, those boils would ooze blood and puss before the person succumbed to extreme fever, chills, nausea, pain, and finally death. Bubonic plague spread through unclean drinking water and vermin like rats and fleas. It could kill overnight. To the people of medieval Europe, bubonic plague seemed like God's punishment. To help manage the spread, sailors were often quarantined.

Black Death still exists today. When caught early, bubonic plague is most often now easily treated (via the World Health Organization).

The official Plague Orders of London's Lord Mayor

The sheer number of dead in the late 17th-century outbreak of Black Death in London forced many traditional burial practices to be abandoned. To address the calamity and help curb the spread, London's Lord Mayor, Sir William Lawrence, issued what were known as the Lord Mayor's orders. In them, watchmen surveilled quarantined households, while searchers, who were typically women, roamed the streets, keeping a rough count of all who had perished. Among other roles were the plague bearers (via History Learning Site).

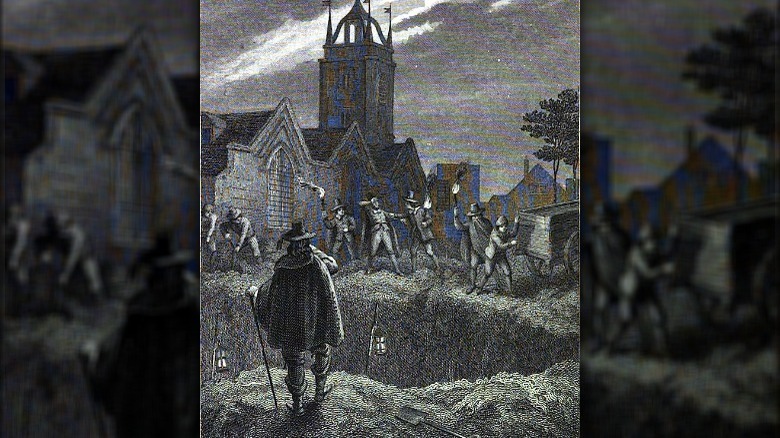

The job of the plague bearer was to move through the city streets of London at night, calling out for dead bodies to be brought out from the homes that had otherwise been shut up due to infection. This task was performed under cover of darkness to help maintain social order, as Art in Society explains. Little could be done to help those infected except lance the boils and hope for the best. Blood-letting was also a common if ineffective treatment tried at that time (via History). Whenever possible, the corpses were to be buried immediately. When that grew impractical, mass graves were established, where bodies were unceremoniously dumped.

Who were the plague bearers?

Naturally, a select few were willing and able to fulfill the unsavory and dangerous tasks of a plague bearer. Typically men with few other options, plague bearers were most often from the lowest rungs of society. They were paid for the service and for many, it was the most money they ever made. Plague bearers were said to smell of death, and otherwise they were known to show little reverence for their ghoulish employment Some accounts from the time have them offering up dead bodies for firewood, perhaps in jest.

Assuredly, some plague bearers themselves caught plague and died, but many misguidedly believed they were immune. One way that plague bearers thought they might protect themselves from infection was to smoke tobacco while they worked. To be consistently enshrouded in smoke was incorrectly believed to offer immunity, as was bathing in rosewater and vinegar, or inhaling aromatic herbs (via History). Given the nature of their work and the consistent exposure to pestilence, men employed as plague bearers were housed away from the public. By all accounts, they did little to change the negative public perception of who they were or the distasteful nature of their work, according to Art in Society.

'Bring out your dead!'

As is parodied in the 1975 classic comedy film "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" (via IMDb), plague bearers really did roam through the streets of London pushing what were called "dead-carts." Working in teams, one plague bearer held a torch, while another, the "linke man," clanged a bell, shouting out to anyone listening, "Bring out your dead!" Just like in "Monty Python," some nearly dead souls were also often piled onto the carts, as were individuals who may have collapsed or taken ill and died for some other reason. Households with dead to collect were sometimes ignored until they offered the plague bearer a bribe (via Art in Society).

After a dead body was given over, the job of a plague bearer turned even more ghastly. The bodies were dragged and piled onto the "dead-carts" with a long pole that had a hook at the end of it. The dead corpses were otherwise roughly handled and stacked one on top of the other like a cord of wood. At times the sheer number of dead bodies was such that daytime collections and burials were allowed. The public response was such that the job was rarely performed in the daylight.

The end of the Great Plague of London

By 1665, the bubonic plague in London began to subside as it did all throughout England. With that, the surviving plague bearers were left unemployed. Vestiges of the bubonic plague and its victims are memorialized in a common playground song to this day, "Ring-a-ring of roses," although "dead" after the line concluding "all fall down" is most often omitted. One wonders if any plague bearers sung the tune while they went about their grim business. Occasional cases of the plague would continue to crop up throughout 1666 and '67, but not to the extent previously seen.

Contributing to the decline of the bubonic plague in England could be quarantine measures adopted by the Lord Mayor, combined with colder weather killing off disease-carrying fleas. The Great Fire of London in 1666 may have also helped ease the suffering in that small way, while causing much more pain in many others. Generally, though, the Great Plague of London is thought to have naturally burned itself out. And with that, one of the grisliest jobs ever undertaken also went extinct.