What The Lincoln Memorial Dedication Ceremony Was Really Like

While the Lincoln Memorial may feel ancient, it's actually only 100 years old.

May 30, 2022, is the 100th anniversary of the dedication of the memorial. The dedication ceremony was attended by around 50,000 spectators, according to the National Park Service. Ironically, they were racially segregated. Armed soldiers escorted black spectators to a roped-off area farther from the memorial, behind white spectators, according to the History Channel.

The memorial had been in the works since just after Lincoln's assassination, but it wasn't until 1911 that Congress approved the building of the memorial and allocated funds to it. A lot of different designs for the monument were rejected, including ones shaped like an Egyptian pyramid and a ziggurat. The final design was meant to resemble the Parthenon in Greece. It was a former Confederate soldier turned senator who broke ground on the building in 1914. This design, and the building itself, were meant to symbolize the reunification of the nation following the Civil War.

Famous attendees of the dedication

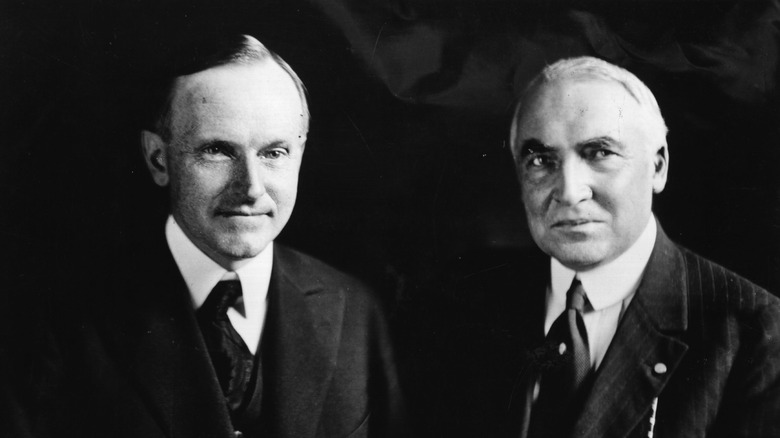

The dedication of the Lincoln Memorial was attended by the sitting president Warren G. Harding, Vice President Calvin Coolidge, and the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, former president William Howard Taft. Harding spoke at the event, emphasizing that the memorial was as much intended for modern Americans as for Lincoln (via the National Park Service). His speech followed an invocation by Reverend Wallace Radcliffe from the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, which Lincoln had attended, and a speech by Robert Russa Moton, president of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Also in attendance was Lincoln's oldest and last surviving son, Robert Todd Lincoln, who was 78 at the time. He had served as Secretary of War under presidents James Garfield and Chester Arthur, as well as Minister to Great Britain under President Benjamin Harrison. He had taken a great interest in the building of the Lincoln Memorial, visiting the site during construction and often asking his driver to take him past it. He didn't speak at the dedication, but did receive an ovation from the crowd (via the National Park Service).

Moton and his speech

Robert Moton was the only African American speaker at the event, and he wasn't allowed to sit on the platform with the other speakers, according to the History Channel. His speech was reviewed by government officials ahead of time, and Taft wrote to him requesting that he cut much of it, as some of the material could be considered controversial. Specifically, much of what Moton had to cut was about Lincoln's legacy being unfinished because of the racism still prevalent in the U.S. at the time, according to The Washington Post.

Moton was the second president of the Tuskegee Institute, a historically black university, after Booker T. Washington, and he had been chosen as a speaker because he was considered "safe," unlikely to say anything contentious (via the National Park Service and The Washington Post). He had written to Harding a year earlier with ideas about how to improve race relations in the U.S (via the National Park Service). According to The Washington Post, the Lincoln Group of the District of Columbia — the oldest organization dedicated to researching Lincoln — wants to right past wrongs by inviting Moton's descendants to the 100th anniversary of the dedication, which will honor Moton and acknowledge the censorship of his speech.