The Unusual Link Between A Lenni-Lenape Chief And 18th-Century New York Politics

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Not one single person would react kindly to a stranger showing up on their doorstep and saying, "Oh, hi. You live here? Right. So this home is mine now. We cool?" And yet, practically from day one, this is what indigenous groups of people throughout the Americas have had to deal with for centuries. More often than not, as we all know by now, such confrontations ended disastrously. Guns, germs, and steel meant that the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés razed the Aztecs from their seated empire in 1521 (via World History), Portugal settled São Vicente in Brazil in 1532 (via World History), England settled Jamestown in 1607 (via the National Parks Service), France settled Quebec in 1608 (via National Geographic), and many, many more.

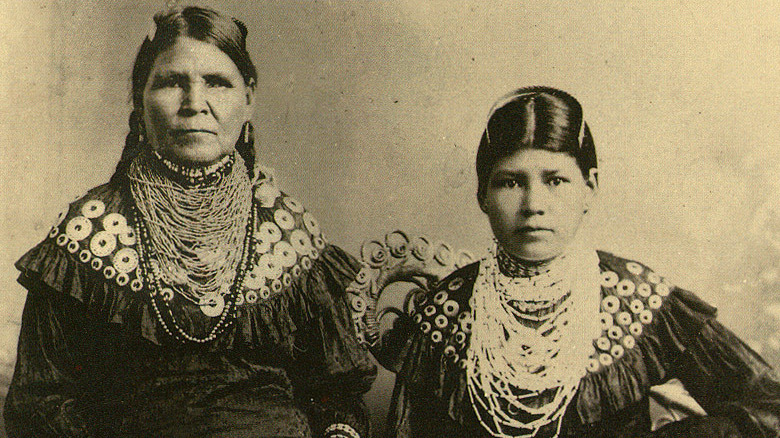

Each stage of deeper and deeper settlement — essentially incursions into occupied territory — pushed existing peoples into further and further corners. It makes sense that "primitive Indians," as they were typically depicted by white colonizers (via Facing History), often responded with violence. But even amidst increasing hatred and potential annihilation, some tribal leaders tried their best to broker peace. One of them, Lenni-Lenape Chief Tamanend, became a legend in the future U.S., no matter how his story has faded from history.

Along with Quaker settler William Penn, Tamanend's efforts not only built a peaceful co-existence in modern-day Pennsylvania but also had a lasting impact on the later New York political institution, Tammany Hall (via Hidden City).

The People Who Live Downriver

The Lenni-Lenape were not a single, homogenous tribe with one shared language. As West Philadelphia Collaborative History note on their website, "Lenni-Lenape" (also just "Lenape," literally "Original People") refers to a whole host of tribes, groups, language families, and dialects spread throughout modern-day Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and parts of Maryland and Connecticut. Depending on the region, traditions could vary greatly. But more often than not, individuals and families lived in smaller wigwams and moved locations every 20 years or so to utilize new soil for farming purposes. Their concentration along the Delaware river led to them being dubbed "Delaware Indians" by early European settlers.

Dutch, Swedish, and Finnish explorers and fur traders were among the first to have regular contact with the Lenape. The Dutch settled along the Hudson River and claimed the entire region from the Delaware River to the Connecticut River, including Manhattan Island, for themselves (via the Hudson River Valley Institute). From the 1630s through 1670s, bit by bit, companies such as the Dutch- and Swedish-founded New South Company bought land, set up outposts, and worked their way southwest.

At the same time, Quakers started settling in the area around the 1660s. Quakers, also known as the "Religious Society of Friends," arose as a Christian sect during the English Civil War and fled England to escape religious persecution (via Ancestral Findings). These people, outcasts themselves, were the ones who brokered peace with the Lenape.

Peace between Tamanend and Mikwon

It was around this time that Tamanend — also called Tammany — became chief among the greater Lenni-Lenape population. As Hidden City described it, Chief Tamanend was reputed as wise, kind, and generous. His name, in fact, means "Affable One." And in a case of affable meets amenable, Tamanend and the Lenape were fortunate enough to cross paths with Quaker William Penn.

Penn, who had been arrested in England for his dissenting views on the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, per US History, fought governmental persecution before trying to establish an independent Quaker colony in the so-called "New World." Dutch control over the Hudson Valley fell around 1677, according to the Hudson River Valley Institute, and by 1681 Penn received a huge plot of land southwest of New Jersey in payment for a loan that England's King Charles II had received from Penn's wealthy father. That area, which combined Penn's name with his preferred moniker for the land, Sylvania ("woods" in Latin), formed the nascent "Pennsylvania."

In 1682, Penn — called "Mikwon" by the Lenape — and Chief Tamanend authorized the "Treaty of Amity and Friendship," an informal, unwritten, peacefully conducted pact, per Hidden City. Penn paid for some Lenape land with "various goods," received a belt made of wampum beads in return, and everything was hunky-dory. Tamanend proclaimed that they would "live in peace as long as the waters run in the rivers and creeks and as long as the stars and moon endure."

The rise of Tammany Hall

As Hidden City explained, Chief Tamanend's renown grew until he became a veritable folk hero and "patron saint of America." He was even later nicknamed "King Tammany" to stick it to King George III during the American Revolutionary War. While writing from Philadelphia, U.S. founding father John Adams declared on May 1, 1777, that the date was "King Tammany's Day," stating, "[t]he People here have sainted him and keep his day."

"Tammany Day" spread outside Philadelphia during the 1770s, according to the Delaware Tribe's explainer. Groups of fans started calling themselves the Sons of Saint Tammany (or "Tammanies"). Calendars from the time even mark May 1 as "Saint Tammany's Festival." In 1789 (possibly 1786), the Society of Saint Tammany, also known as the "Columbian Order," was formed in New York City, with Tammany Hall as their headquarters (via Thought Co). Their goal? They were kind of a hybrid political chit-chat club meets indigenous people's cosplay operation. They called Tammany Hall "the wigwam" and their leader the "Grand Sachem."

While this definitely constitutes some odd and icky cultural appropriation, it's hard to tell if these folks were simply wielding Chief Tamanend's name for their own political ends. But by 1820, the Tammany Society started veering towards criminality.

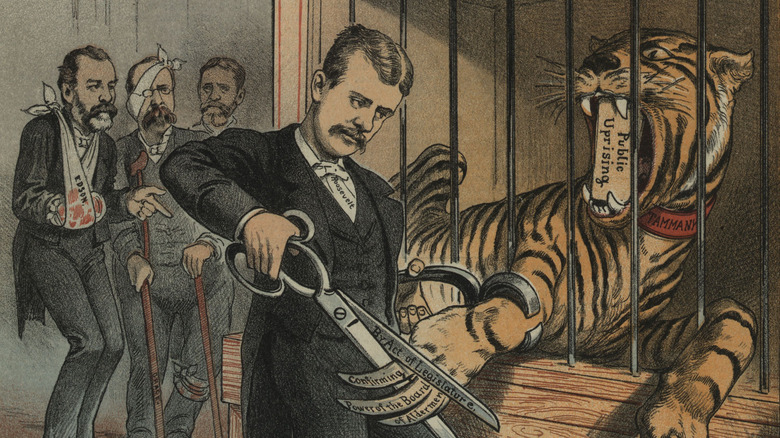

Corruption within Tammany Hall

Now, we turn to the precise, unsavory end where we might expect moose lodge-dwelling, indiginous cosplay-wearing white folks who call their leader "Grand Sachem" to wind up — that's right, politics. As Thought Co described it, the Tammany Society gained legitimate political power from the early to mid-1800s. They took advantage of "the Spoils System," a highly corrupt method of appointing administrative positions within government to those who'd supported a particular presidential candidate (also via Thought Co). America's seventh president, Andrew Jackson, pushed for this system and was supported by none other than those of Tammany Hall. Unsurprisingly, the Tammany Society began accumulating federal jobs within New York City.

On the surface, it looked like the Tammany Society had laudable, even noble goals. They were successful in pushing for the enfranchisement of property-less white men, per History, and supported the rights of working people, especially immigrants. By the 1850s, Tammany became especially associated with New York City's Irish immigrant population and even took part in food-and-coal drives during harsh winters.

But the other hand, they were also stuffing ballot boxes and roughing up locals during election time, per Atlas Obscura. Through the 1890s, the Tammany Society basically transformed into a veritable crime syndicate. They had two "bosses" — Boss Tweed and Boss Croker — who were involved in numerous scandals and criminal rings while amassing millions of dollars. It took until the 1930s for their power to wane, and the 1960s for Tammany to die off completely.

Lasting monuments to peace

At present, we've got to separate Chief Tamanend's affability and openness and the hard work of William Penn (and those who built peace between the Lenni-Lenape and Pennsylvanian settlers) from the shameful mess into which Tammany Hall devolved. And it should go without saying that Tammany Hall's eventual corruption is no stain at all on Chief Tamanend and his name.

While history has somewhat forgotten the Affable One, he hasn't vanished completely. Since 1995, folks getting on I-95 at Front and Market Streets in Philadelphia might notice a tall, bronze statue off to the side of the road. There stands Tamanend, at the top of a brick pillar posed on the back of a turtle representing Mother Earth, with an eagle as a messenger of the Great Spirit on his shoulder. The eagle grasps in his talons a wampum belt similar to the one that Tamanend would have gifted to William Penn, per Hidden City. And in 2003, two resolutions were brought to the U.S. Congress seeking to officially establish May 1 as "St. Tammany Day." While it hasn't gotten any traction yet, here's hoping.

As for the Treaty of Amity and Friendship, French philosopher Voltaire once called it, "the only treaty between those nations and the Christian nations which was never sworn to and never broken," per Hidden City. Such an accomplishment is more than worth applauding, as much as the attitudes of its two leaders are worth emulating.