What It Was Really Like When The Eiffel Tower Opened In 1889

France had much to brag about during the Third Republic, including the most egalitarian society the nation had ever enjoyed (via Britannica). The middle and lower classes savored a more significant share of social and political power than ever before, underscored by universal manhood suffrage. Yet, France had stopped short of a complete Industrial Revolution, which meant it remained a country of consumers, traders, and small producers.

With the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, the French ushered in the Belle Epoque (literally Beautiful Age), which saw a steep rise in living standards for middle and upper-crust families according to ThoughtCo. Known alternately as the Gilded Age in the United States, these decades bore witness to unprecedented economic growth and prosperity, as reported by Oxford Handbooks Online. The end of the 19th century brought countless technological advances and relative peace domestically and internationally.

In essence, life looked fantastic for many, especially when contrasted against the events of the previous century like the Storming of the Bastille and the French Revolution with its bloody Reign of Terror. The French hosted the 1889 Exposition Universelle, a world's fair of epic proportions, to commemorate these achievements. The highlight of this event was the Eiffel Tower, a temporary structure that became France's most-loved national monument. Here's what it was like after the Eiffel Tower opened in 1889.

Gustave Eiffel presided over the opening tour

In 2017, France began a 15-year-long renovation of the Eiffel Tower with a price tag of more than $300 million, according to Architizer. This is an extraordinary development when you consider that the Eiffel Tower was initially only slated to stand for two decades. Today, the tower and Paris remain so inseparable that it's hard to imagine the French cityscape without it.

But when the Eiffel Tower opened on Sunday, March 31, 1889, with Gustave Eiffel himself presiding over the event, the structure's fate remained far from certain (via Google Arts & Culture). Eiffel showed the first curious visitors around his namesake tower, then the tallest structure in the world, a record it would hold for four decades.

Once they'd had a look around, event organizers displayed a massive tricolor flag accompanied by a 21-gun salute. This first group of visitors oohed and awed at the monument's spectacular views as they joined the first ranks of those who would fall in love with the tower. Today, people celebrate Eiffel Tower Day every March 31 in remembrance of this opening tour, as reported by National Today.

Famous personalities enjoyed the first views

To get an invitation to the Eiffel Tower's inauguration, you had to either be known or know people (via History). Pierre Tirard, the French prime minister, attended the event along with a crowd of noted dignitaries eager to scope out the views from the top.

According to Google Arts & Culture, people traveled from all over the world to savor the fantastic aerial vistas afforded by Paris' premier monument. Many of them were household names of the Belle Epoque. The tower would continue as a celebrity magnet, attracting the likes of the Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII), the Princess of Wales, French actress Sarah Bernhardt, George I of Greece, the Shah of Persia, and Prince Baudouin of Belgium, according to Tour Eiffel. One of the most rugged and notorious visitors would be America's William F. Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill.

But perhaps the most celebrated visit was that of Sadi Carnot, president of the French Republic. After falling in love with the soaring views of the tower made of delicate ironwork, he put his money where his mouth was. He awarded 100 francs to each employee, including the printing staff of the tower's newspaper, Le Figaro. (More on Le Figaro in a bit.)

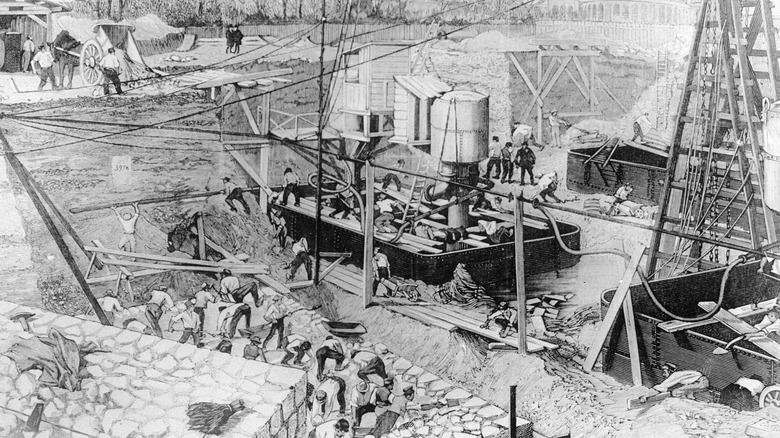

The Eiffel Tower's construction workers got in on the fun

Besides dignitaries and politicians, 200 laborers on the Eiffel Tower attended the festivities, per History. They included 150 construction workers and 50 designers and engineers whose hard work brought Eiffel's vision to life (via the Tour Eiffel). The feat these laborers achieved was monumental. It included the assembly of 18,038 metallic components using 2,500,000 rivets. The building required 7,300 tons of iron and 60 tons of exterior paint. It also had five elevators.

While the monument bore the name of Gustave Eiffel — the owner of the company that built it – the engineers responsible for the design were Émile Nouguier and Maurice Koechlin. They also brought architect Stephen Sauvestre onboard to improve the aesthetic. Inspired by New York City's Latting Observatory, Eiffel would describe the tower as "not only the art of the modern engineer but also the century of industry and science in which we are living" (per Architizer).

Workers at Eiffel's factory in Levallois-Perret assembled the more than 18,000 parts of the tower before another set of workers took over at the site. Tour Eiffel describes what happened next as the "assembling [of a] gigantic erector set." During the construction of the Eiffel Tower, laborers accomplished the work in record time, taking two years, two months, and five days to complete. All told, only one worker perished during the construction (reports History), an incredible achievement considering the nature of the work and late 19th-century safety standards.

Lack of elevators didn't deter visitors

When the Eiffel Tower opened, its elevators were incomplete, according to History. This meant only the hardiest of guests accompanied their tour guide, Gustave Eiffel, to the top. Although this might sound like a significant deterrent, visitors made the laborious journey up the stairs in droves.

Tour Eiffel tells us that within the first week of its opening, nearly 30,000 individuals clambered up the 1,710 stairs of the 1,000-foot-tall structure, feasting their eyes on the panoramic views it afforded. Despite the still temporary nature of the structure, these thronging crowds thrilled at the dizzying heights of the monument. Many also came to appreciate the modern achievement, dubbed the "Iron Lady" (via Tour Eiffel) as a true masterpiece of architecture.

The Eiffel Tower's elevators started functioning on May 26 and came from an American company known for its superior quality standards, per Live Science. Once the elevators finally worked, even greater numbers flooded the monument in pursuit of the best views of the City of Light. It must've felt thrilling for the most engineering-minded individuals to see how these lifts pushed the envelope on load transportation to what seemed like impossible heights. What's more, the engineering proved enduring, as attested by the fact you can still ride two of the original elevators today.

Controversy swirled around the Eiffel Tower's design

Despite the glowing reception Gustave Eiffel's urban monument received from the in-crowd, another group of people vehemently opposed his vision. These included some of the most influential artists, architects, and writers of the day who lamented the Eiffel Tower as a "tragic street lamp" (via All That's Interesting). They lobbed countless insults at the structure, organizing a petition to halt construction or ensure it got disassembled immediately after the Exposition Universelle.

The opposition included thinkers like Guy de Maupassant, who labeled the Eiffel Tower "a diabolical undertaking of a boilermaker with delusions of grandeur," as quoted by All That's Interesting. In other words, it wasn't uncommon for Parisians to have mixed feelings about the structure and how it changed the feel and look of their city.

The petition, organized by none other than Charles Garnier, famed architect of the Paris Opera House, made the rounds gaining 300 signatures and plenty of momentum (per Live Science). Published in Le Temps on Valentine's Day, it appealed to the sensibilities and nostalgia of Parisians. But Eiffel countered their narrative, declaring the iron tower symbolic of the nation's progress, per Architizer.

Anybody could enjoy the views the tower afforded

From skyscrapers with speedy elevators to airplanes, technology has made aerial vistas a standard part of life for people today. So, it's easy to forget just how amazing the nearly 1,000-foot-tall Eiffel Tower's panoramic views were in 1889, according to Google Arts & Culture. But they boggled many a 19th-century mind. Put another way, the structure democratized views of Paris once monopolized by only a tiny segment of affluent adventurers (via Live Science).

The tower permitted anybody capable of climbing stairs (or later riding an elevator) to savor thrilling views of the city once reserved solely for those with access to a hot air balloon. In other words, the view proved unprecedented for the vast majority of Parisians and visitors who flocked from the four corners of the globe, as reported by Tour Eiffel. As the entrance to the Exposition Universelle (via Britannica), the Eiffel Tower took human vision to new heights, a fitting characteristic for a gathering that sat poised on a bright future.

The Eiffel Tower pushed the envelope regarding the future of architecture and cityscapes (per Google Arts & Culture). It also excited individuals to try their hand at shattering records associated with the structure while enjoying soaring views of France's premier city. Among the most famous was a baker from Landes who donned stilts before climbing the 347 steps to the first floor.

Visiting the Eiffel Tower could get experimental

Gustave Eiffel remained keenly aware that some Parisians wanted to tear down his elegant masterpiece, according to Live Science. And the last thing he wanted to see was his beloved building demolished at the end of the Exposition Universelle. In response, Eiffel promoted it as useful to science and encouraged researchers to employ it in experiments related to electricity, gravity, and more, even installing a laboratory.

Pushing these uses fit perfectly with Eiffel's claim that the tower represented "not only the art of the modern engineer but also the century of industry and science in which we are living" (via Architizer). Eiffel did more than give lip service to science, however. During the construction of his grand ironwork monument, he had the names of 72 scientists engraved into the first floor, as reported by Tour Eiffel. The height of the tower made it irresistible for certain types of experimentation. Among the first was a massive copy of Foucault's pendulum, attached to the second floor's underside. Researchers also placed a mercury pressure gauge at the top of the structure, permitting calibration of gas and metallic pressure gauges for various industrial purposes.

The elevations afforded by the tower also made it easier than ever before to monitor atmospheric pressure, temperatures, rainfall, wind speed, and humidity. Eiffel would have these measurements regularly published, footing the bill himself. These efforts proved essential to developments in modern meteorology and climatology by emphasizing long-term data collection.

The Eiffel Tower was meant to impress

The inauguration of the Eiffel Tower proved splendid. It started with the official opening on March 31, followed by a public opening on May 15 coinciding with the Exposition Universelle's start, per Google Arts & Culture. Millions of tourists headed to Paris to scope out the event, and 1,953,122 turned out specifically for the Eiffel Tower. Crunch the numbers, and that's roughly 12,000 visitors daily.

The 1889 Exposition Universelle encompassed 237 acres, including portions of the Champ de Mar, according to W&L Paris. Exhibits also extended along the Seine, boasting 61,722 exhibitors housed in 80 opulent buildings. It included stunning gardens inviting spectators to walk the meandering grounds and visit great domed pavilions (via Tour Eiffel). Roughly 30 of these buildings were national pavilions, and the United States dominated the event. One of the reasons for this was the decision of European monarchies to boycott the event. (They argued that celebrating the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution glorified displacing and killing royalty.)

France had experienced years of political tumult leading up to 1889. This included defeat during the Franco-Prussian War and the revolt of the Commune. But the nation had navigated these troubling events, finally emerging as an honest-to-goodness Republic. What's more, they'd closed the industrial and colonial gaps with the British Empire. The Exposition Universelle represented a way for the Third Republic to showcase its achievements, and the French did so in grand style over six months, attracting more than 30 million people.

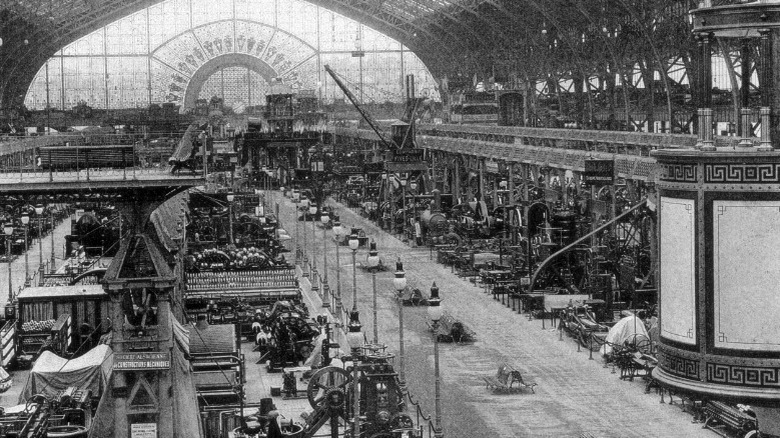

It marked the central attraction for the Exposition Universelle

Besides checking out the centerpiece of the Exposition Universelle and tallest building in the world, visitors came to see the Gallery of Machines, the largest metalwork structure in the world, per Tour Eiffel. Ferdinand Duteret designed the 1,452-foot-long structure. Inside, two bridges 20 feet above the machines permitted viewers to look down on the 16,000 innovative devices located below, including 493 of Thomas Edison's inventions (via W&L Paris). Yet, France dominated the exhibit with inventors taking up nearly three-fourths of its space.

Besides the Gallery of Machines, more than 60,000 exhibits filled the Exposition Universelle. Forty percent were foreign attractions, including those from North America, South America, Europe, and France's overseas colonies. As one individual noted after visiting the expo, "Half the civilized world will be lured to Paris, and most certainly with good reason, for this is the most beautiful exhibition the world has ever seen," per W&L Paris.

To gain entry to the event, spectators paid one franc per person. For those who wished to climb the Eiffel Tower, an additional five francs charge applied (via Tour Eiffel). Once visitors conquered the stairs, handy maps permitted them to orient themselves to Paris' most iconic attractions (via Google Arts & Culture).

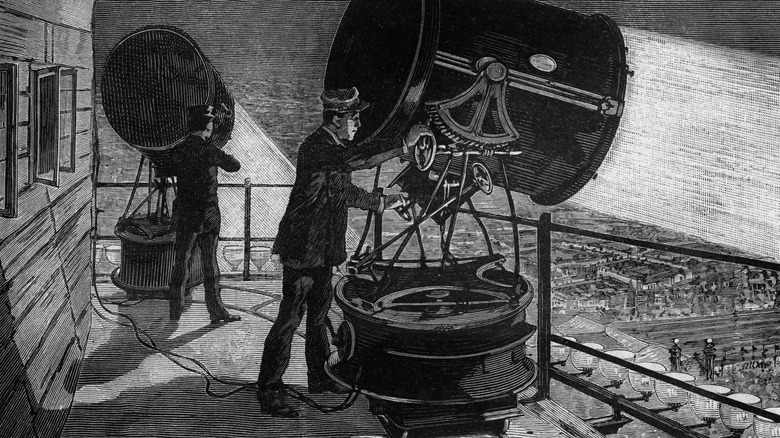

The Eiffel Tower glittered with gaslights

Every evening, officials illuminated the Eiffel Tower with gaslights, per Tour Eiffel. And the campanile housed a tricolor beacon with the nation's colors, making for a glittering spectacle. Exposition Universelle officials relied on two projectors, which they placed atop a circular rail located at the tiptop of the monument. These fanciful displays were punctuated morning and evening by cannon fire announcing the open and close of each day. Besides the gaslit Eiffel Tower, electricity made a glittering appearance at the show.

Unlike previous electrical lighting displays, however, exhibits at the 1889 expo focused on more than usefulness. Creators wished to explore the esthetic possibilities of electricity. An example of this was the massive, illuminated pear created by Thomas Edison with 20,000 light bulbs. One attendant of the Exposition Universelle noted, "Everything shines, glitters, blazes in a perpetual feast for the eyes" (per W&L Paris). These new uses of electricity helped cement the United States' role at the forefront of innovation. No matter their nationality, inventors put the world on notice about how life-changing inventions such as electrical lighting would soon prove.

Of course, all of this sparkling came with a hefty price tag. The Exposition Universelle spared no expense for entertaining and astounding those in attendance. A combination of private investors, the French government, and the city of Paris contributed 47 million francs to realize the illuminating event.

Tower-based boutiques and restaurants invited visitors to linger

Besides the incredible views afforded by the Eiffel Tower, a collection of tasteful boutiques and fine restaurants invited tower visitors to stay awhile, according to Tour Eiffel. Visitors were greeted by an assortment of souvenirs for the Eiffel Tower and the larger Exposition Universelle. They also could get their photos taken at booths and rent binoculars for better views of the city and the Exposition Universelle below.

The four restaurants sat on the first floor of the tower and were constructed as wooden pavilions laid out by Stephen Sauvestre, per Tour Eiffel. Each pavilion could seat an impressive 500 people, and the kitchens of the restaurants were tucked on the platform's underside. They included a Russian restaurant, an Anglo-American bar, a French restaurant, and a Flemish restaurant. Not only did each of these restaurants offer unique takes on the cuisine they fronted, but their pavilions showcased different architectural styles, complementing the refreshments they offered.

The Russian restaurant was opulent in its Eastern decadence and sat between the Northern and Eastern pillars. The Anglo-American bar played on the latest trends in dining with a large room and a bar located in the middle. The so-called Flemish restaurant served the German-influenced Alsatian food of eastern France. As for the French restaurant, called the Brébant, it sat on the Champ de Mars side of the first floor, garnering a high-end reputation.

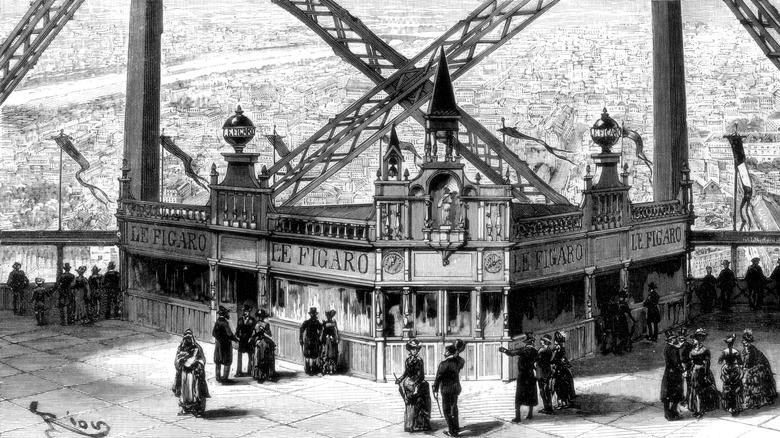

The Eiffel Tower printed a daily newspaper

Famed French journal Le Figaro set up a printing office on the second floor of the tower where they published a daily newspaper, as reported by Tour Eiffel. Those who bought a copy of the newspaper could opt to have their name printed in it as a memento of visiting the monument and the Exposition Universelle. The office stayed up for the six-month duration of the expo, permitting visitors to find out more about the craft of news printing.

According to Tour Eiffel, the pavilion housing Le Figaro's office included a printing press and editorial office. Twenty-four employees worked there, including proofreaders, printing technicians, and journalists. The pavilion included impressive bay windows, affording a bird's eye view of the area.

The news journalists employed in the Eiffel Tower focused primarily on stories related to the expo. And they kept to a rigorous printing schedule, publishing a new edition nearly every day. This incredible tower installation must've made visitors feel as if they were a part of the news-making action in unprecedented ways. It also emphasized the significance of the event as a beacon of future societal and technological developments.

Visitors postmarked letters from the Eiffel Tower

Besides the four restaurants located on the first floor of the Eiffel Tower, visitors also found a post office (via Tour Eiffel). Although the smallest post office in Paris, many also considered it the most beautiful. Stamp collectors especially loved it because their collectibles could be postmarked from the tower.

In a truly forward-thinking move, the 1889 Exposition Universelle premiered a new type of correspondence in France, the postcard. These took off like wildfire as people rushed to post a message from the top of the world. Conveniently, each floor of the monument contained mailboxes. That way, tourists could track their journey, via post, through all the levels of the tower.

Although many of the features of the 1889 Exposition Universelle are no longer discernible on the Parisian landscape, visitors can still check out this tiny post office, as reported by Travel + Leisure. Today, people still visit this diminutive location hidden between boutiques. There, postcards abound as well as the chance to postmark correspondence from Eiffel's visionary monument.

Honored visitors found Gustave Eiffel up top

The Eiffel Tower was chock full of incredible boutiques restaurants and other installations like the newsroom for Le Figaro and even a post office (via Tour Eiffel). But one of the most fascinating aspects of the structure remained Gustave Eiffel's office, located at the pinnacle of the world's tallest structure. There, he welcomed notables like Thomas Edison and Charles Gounod for discussion and to savor incredible panoramic views. Interestingly, Gounod, a French composer, had once signed the petition opposing the Eiffel Tower's construction.

An open-air balcony completed Eiffel's office, which, despite its heavenly elevation, didn't lack for amenities, as reported by Tour Eiffel. These included a fully furnished kitchen, a bathroom, and a living room. Among the furniture were tables, three desks, and even a piano. Besides using this space for meetings, it also offered comfortable accommodations to scientists involved in experiments at the tower. Reports would describe this special apartment as "furnished in the simple style dear to scientists," per Atlas Obscura.

After Eiffel's death, his offices reverted to use as storage for technical facilities. But the office has been reopened to the public. Today, it contains wax sculptures of Gustave Eiffel with Thomas Edison and Eiffel's daughter Claire Eiffel. This evokes the scene when the famous American inventor visited Paris to take in the 1889 Exposition Universelle for himself. At this meeting, Edison famously gifted Eiffel with one of his first sound recording mechanisms.

It proved emblematic of late 19th-century Paris

Although controversy ushered in the Eiffel Tower, locals quickly fell in love with the structure, as reported by Live Science. As the monument continued to astound those who visited it, members of the opposition also warmed up to it. Many of those involved with the petition to tear it down would eventually publicly apologize for opposing the structure. We can only imagine the exhilaration a visit to the tower must've included to cause such about-faces.

Parisians felt a sense of pride looking at a structure that represented all that Paris had come to stand for as the heart of French democracy, modern art, and modern architecture (via Tour Eiffel). Visitors felt equally impressed by the intricate contemporary structure, which soon became the most recognizable cityscape in the world.

Although Eiffel recognized the merits of his visionary monument, he likely couldn't anticipate the impact it would have on the city of Paris and his French homeland. Not only would it become the standard to which all other monuments would be compared, but it would also become a symbol of France's pride and future.