The Remarkable Life Of Sweden's Queen Christina

Queen Christina of Sweden continually did the opposite of what people expected of her. Considered unusual in her own time, she remains a fascinating character to this day. She became queen just before her 6th birthday after her father died in the Thirty Years' War, a European religious conflict (via Britannica). By 14, she was attending national council meetings, and at 18, she began to rule in her own right, according to History Today.

Queen Christina and her advisors achieved much during her reign, making strides in trade, manufacturing, and mining, and establishing a colony in North America, "New Sweden" (via Britannica and the Library of Congress). Her achievements were hampered by her tendency to overspend and to give away crown lands. However, during this time period, Sweden's first nationwide school ordinance was implemented, and its first newspaper was established. Christina also advocated for peace at the end of the Thirty Years' War. Amazingly, despite those accomplishments, her reign isn't one of the things she's best known for.

Christina was unusually educated for her time

Though Queen Christina's mother wasn't too pleased with the birth of a daughter, her father doted on her. He insisted that she be educated like a boy since she was heir to the throne. Her head tutor was Johannes Matthiae, a theologian who influenced Christina's beliefs on religious tolerance.

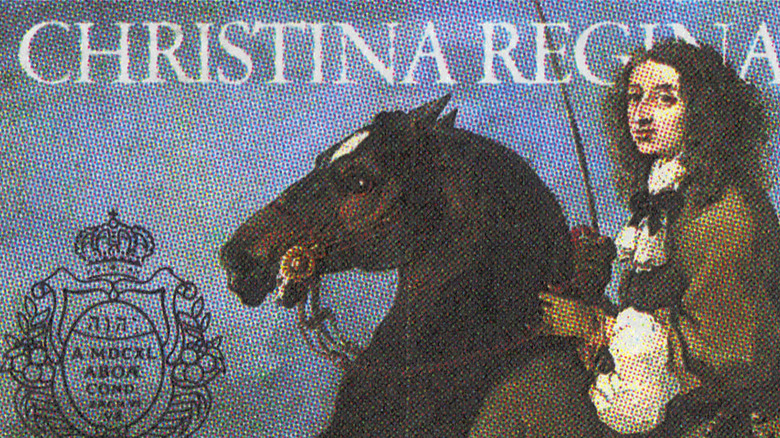

According to the International Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP), Christina knew at least six languages: Swedish, French, Latin, German, Italian, and Spanish. She may have also studied Hebrew and Arabic. She studied classical philosophy and military strategy and learned how to fence and ride a horse as a king would. According to Britannica, her regent and chancellor Axel Oxenstierna taught her politics, and she corresponded with French philosopher René Descartes and invited him to Sweden to tutor her. He was one of many scholars based at her court. With such attention given to learning, it's no surprise that her motto was "wisdom supports the nation" (via the Library of Congress).

Christina abdicated at age 27

In 1651, Queen Christina shocked her advisors by announcing her desire to give up the throne in favor of her cousin, Charles Gustavus. She claimed the nation and the army needed a man to lead them, according to History Today. She said the burden of ruling made her unwell, and her abdication was a matter of debate for three years before the Swedish legislature agreed to it (via Britannica).

The real reasons for her abdication have never been completely clear, but it probably also had to do with her desire to convert to Catholicism, which was illegal in Lutheran Sweden. She converted in 1655 after leaving Sweden and went to Rome, where the pope happily welcomed her, gave her a place to live, and supported her financially. However, her odd behavior, skepticism about religion, and unwillingness to make public demonstrations of piety soon alienated her from church authorities (via the International Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Britannica).

Christina didn't want to marry

Another likely factor in Queen Christina's decision to abdicate was her desire not to marry. As queen, she was expected to produce heirs, and to that end, she had at one point considered marrying her cousin Charles Gustavus, who was very interested in the idea. She kept the possibility on the table, but like Queen Elizabeth I of England, she realized she had more power unmarried than married. She kept Charles and her advisors guessing on the subject until her abdication (via Your Dictionary).

Christina might have been averse to marriage because of her sexuality or gender identity. She frequently dressed in male clothing, particularly after leaving Sweden, according to the International Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Britannica suggests that she was uncomfortable in her femininity after spending so much of her life in the company of men. According to Your Dictionary, there were contemporary rumors that she had a female lover, her friend Countess Ebba Sparre. However, there were also rumors that she had an affair with a man in Rome, Cardinal Decio Azzolino (via Britannica). Centuries later, the truth will probably remain a mystery.

Christina tried to become ruler of Naples and Poland

After only a year or two, Queen Christina seemed to miss ruling her own territory, and she hatched a plan with French political minister Cardinal Mazarin and the Duke di Modena to seize Naples — which was ruled by Spain at the time — and become its queen (via Britannica). She would then name a French prince as her heir. By 1657, when she visited France, the plan fell apart. She shocked both the French and the Romans by ordering the execution of her equerry, Marchese Gian Rinaldo Monaldeschi, because she believed he had betrayed her plans to the pope. However, she refused to tell others why she had executed him — besides the fact that she had the royal authority to do so.

Ten years later, during a stay in Germany, she obtained the pope's permission to vie for the Polish crown. Her second cousin, John II Casimir Vasa, had recently abdicated. However, this plan also failed, and she returned permanently to Rome.

Christina had an active later life in Rome

In Rome, Queen Christina stayed involved in the politics of the Catholic Church, including years-long advocacy for a holy war against the Turks. According to Britannica, she even contributed her own pension to the war fund.

This period of Christina's life contributed to her lasting reputation as a patroness of the arts. In her palace in Rome, she had a massive collection of paintings, sculptures, and medallions. Many of the paintings were made by the Venetian school of artists, and the Corsini art museum is now on the former site of Christina's palace. In her day, it was a meeting place for academics, scientists, and musicians. Christina took an interest in astronomy — establishing an observatory in her home — as well as music (via the International Encyclopedia of Philosophy). She advocated for the establishment of the first public opera house in Rome, and she sponsored musicians like Alessandro Scarlatti and Arcangelo Corelli.

Christina was also interested in literature. Her large collection of books and manuscripts is now part of the Vatican Library. According to the IEP, she was a prolific writer herself, penning collections of maxims, defenses of the Huguenots and the Jewish population of Rome, and her own autobiography. Her literary legacy lives on, and not just in the Vatican: The Library of Congress notes that she founded the Accademia dell'Arcadia for literature and philosophy, which still exists in Rome as the Accademia Letteraria Italiana.