HG Wells' Parody Of His Literary Friend Led To A Lifelong Feud

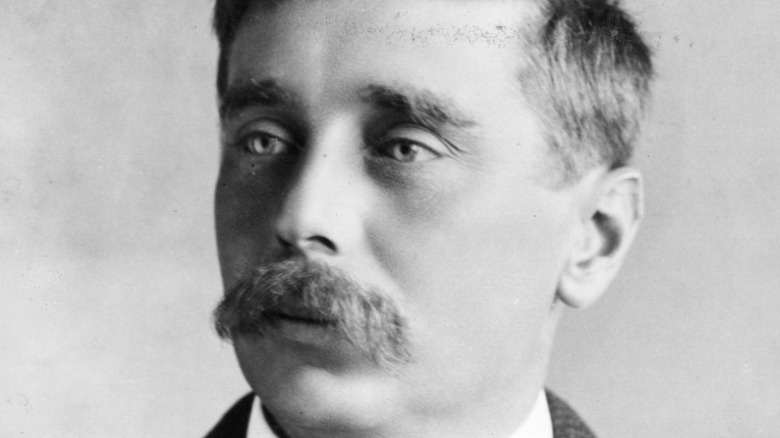

The writer Henry James, who was born in New York but spent most of his life as a celebrated literary figure in the United Kingdom, was an incredibly prolific novelist, short story writer, and playwright whose work was so well regarded that he was awarded the Commonwealth Order of Merit. Similarly, Englishman Humbert Wells (pictured) — better known by his pen name, H.G. Wells – was hailed as a visionary. He was a writer of science fiction, speculative essays, and social critique who would come to be held alongside "Nineteen Eighty-Four" writer George Orwell as one of the most far-sighted and influential authors of the modern age.

Though James was an American and Wells British, and though James was a lifelong bachelor and Wells a married man — with a number of high profile affairs to his name — the two writers appear to have had a great deal in common. But in 1898, the differences between them in terms of their literary careers were particularly striking (via the book "Henry James and H.G. Wells: A Record of their Friendship, their Debate on the Art of Fiction, and their Quarrel"). By the end of the 19th century, James was an established literary figure, a household name, and a well-known celebrity in London's literary and academic circles. However, his readership was dwindling, and he was growing increasingly paranoid about his legacy. Meanwhile, Wells was a wildly popular writer of "scientific romances" — what we know today as science fiction — still in the first flush of his creative life who was yet to be taken seriously by the literary establishment.

The start of a beautiful friendship

With their literary lives serving as each other's inverse, the stage was set for a famous friendship ... and what would become a legendary feud between the two men. Per The New York Times, H.G. Wells first met Henry James (pictured) in 1898, when they immediately formed a dynamic that suited both writers and which would sustain their friendship well into the 19th century. At the time, Wells was the up-and-coming young speculatist, and though he had yet to receive the critical plaudits he would enjoy later, James offered Wells effusive praise. In 1905 James told Wells about being "prostrate with admiration, and that you are, for me, more than ever, the most interesting 'literary man' of your generation — in fact, the only interesting one. These things do you, to my sense, the highest honor, and I am lost in amazement at the diversity of your genius."

Nevertheless, the two writers communicated and debated their ideas "as equals," though James, as the elder of the pair, usually spoke with the voice of authority and experience. To Wells, James — 23 years his senior — was venerable as an established master of letters, who was happy to take on the role of mentor for such talent. James' guidance took the form of what Wells called "loving chastisement."

The two shared famous friends, including "Heart of Darkness" author Joseph Conrad and the poet Stephen Crane. Eventually, however, after countless meetings and lively discussions at James' handsome home at Lamb House in Rye, East Sussex, the tone between the two men changed.

Public pronouncements

Wells, who began his friendship with James humbly and politely, became increasingly assured and confident in his opinions on the nature of art and literature. Their ongoing close friendship was characterized by regular meetings, long discussions, and numerous letters to one another. (Wells' wife preserved his correspondence; more than 40 letters from James survive, while scholars have access to only 11 of Wells' letters to James, who had burned many of his papers.) Nevertheless H.G. Wells and Henry James began to diverge dramatically in their public opinions as to the use of literature and its place in society, an issue that eventually drove the two friends apart.

As reflected in the 1958 The New York Times review of the book "Henry James and H.G. Wells: A Record of their Friendship, Their Debate on the Art of Fiction, and their Quarrel," a collection of their letters and other documents edited by Leon Edel and Gordon N. Ray, their relationship first became strained after they gave contrasting public pronouncements on the use and purpose of literature. In a famous lecture, Wells delivered his beliefs on the purposes of the novel and how it should be used, which, while it didn't name James directly, certainly sketched James' literary beliefs as fundamentally misguided.

When James caught wind of Wells' arguments, he responded in kind, with an article titled "The New Novel," taking aim at the writing practices of younger novelists — his friend Wells included. The young writer responded with a move of literary malice that ended the friendship forever.

Fundamental differences

But what exactly were the two friends arguing about? As Edel and Ray note, the debate was between whether literature should reflect "the voice of the individual" — the default belief of Henry James — or should be a tool through which an author might "engage in the furtherance of social welfare." Put simply, James believed that a novelist's highest aim should be the creation of "art for art's sake," for the development of new aesthetic techniques through which to create the most perfect literature possible for the elevation their readers' souls.

As such, Edel and Ray argue that the disagreement between the two men is representative of anxieties concerning the purpose of art in the earlier part of the 20th century, while the critic Joseph Wiesenfarth has argued that the disagreement was also based on nationalistic tensions. James, as an American practitioner of the techniques of Balzac and Flaubert, was importing a foreign literary aesthetic to Britain, threatening the existence of the "English novel" at a time of great political tension in Europe.

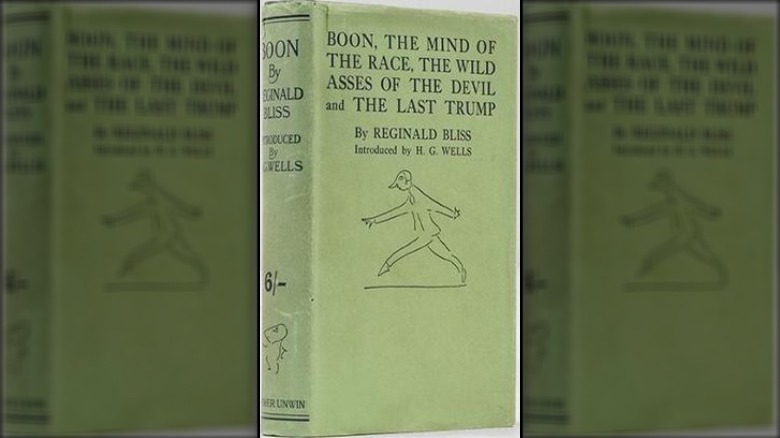

'Boon'

The year 1915 was when the prolific Wells published "Boon," the fourth chapter of which is a sustained attack on his old friend Henry James. Wells writes: "Having first made sure that he has scarcely anything left to express, he then sets to work to express it ... He spares no resource in the telling of his dead inventions."

In "Boon," Wells suggests that James' characters are nothing more than bloodless avatars. According to Wells, his older friend's creations were not believable, as they were essentially "eviscerated people" sucked dry of all corporeal reality. But most memorable perhaps in Wells' long attack on his former mentor was the suggestion that James, in his overwrought later style, resembled a "hippopotamus trying to pick up a pea" (via The New York Times).

Though the image of a hippo hurt James immensely, it might be true to say that Wells' satirical assassination of his old friend and master confirmed in the mind of the older writer that he was also a literary dinosaur. By this time, Wells was "ragingly successful," according to The New York Times, while James was struggling with his late decline in popularity. Wells' attack must have felt like the nail in his coffin, with James sadly believing that the way of literature he had practiced throughout his life was already considered outmoded and due to be forgotten. The quarrel ended what had been a fruitful friendship between the two writers, and though Henry James suffered the more public attack, it was he who ended the argument with dignity.

A famous quarrel

As noted by The New York Times, James wrote in his last letter to H. G. Wells — which he sent following his receipt of "Boon" — that he in fact "live[s] intensely, and am fed by life, and my value, whatever it be, is in my own kind of expression of that." In short, James argued that his way of writing was an accurate reflection of the way he saw the world.

In 1953, the academic Michael Swan published a study of the quarrel, in which, through a close reading of Wells' letters to James, he suggests that the visionary writer harbored a deep Freudian resentment towards his mentor, whom he viewed as a metaphorical father, and that through "Boon" and his subsequent quarrel Wells was enacting a typical Oedipean rebellion against the older writer (via Edel and Ray).

Edel and Ray, however, take issue with Swan's characterization of the underlying motivations behind the feud, and instead invoked the critic E.K. Brown in arguing that the quarrel was actually about "two formulae for fiction" which became incompatible as they also represented different ways of ordering one's life around the business of creating art, though why their friendly debate descended into a vicious quarrel — and what truly motivated it — is still discussed by scholars today. Sadly, the quarrel came to a head only a year before Henry James' death at the age of 72. The disagreement between the two longtime friends was unable ever to be resolved.