Who Won The First Indy 500?

There is arguably no other major event that is associated so closely with Memorial Day Weekend than the Indianapolis 500. Though it has often been pointed out that the event has lost a good deal of popularity through the years, it is still one of the world's most iconic auto races, and it has made racing legends out of many an individual — multiple-time winners Al Unser Sr. (and his namesake son, Al Unser Jr.), A.J. Foyt, and Helio Castroneves are among the names that come to mind. Many a Formula 1 standout has also excelled at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, from Graham Hill and Jim Clark in the 1960s to Juan Pablo Montoya in more recent years.

It's hard to fathom that the Indianapolis 500 is now more than a hundred years old, so how were things back in 1911 when the first such race was held? Well, for starters, protective gear (e.g. leather helmets) was very primitive, and the cars were naturally much slower and less aerodynamic. The event wasn't even called the Indianapolis 500 yet — officially, it was the International 500-Mile Sweepstakes Race. Talk about old-timey and cumbersome names. As for the person who won the very first Indy 500, he was a fairly well-known driver in those days, and as it turned out, he was also a one-race wonder at the IMS who, thanks to his primary line of work as an engineer, was quite the innovator in auto racing's earlier years.

Ray Harroun was the first-ever winner of the Indianapolis 500

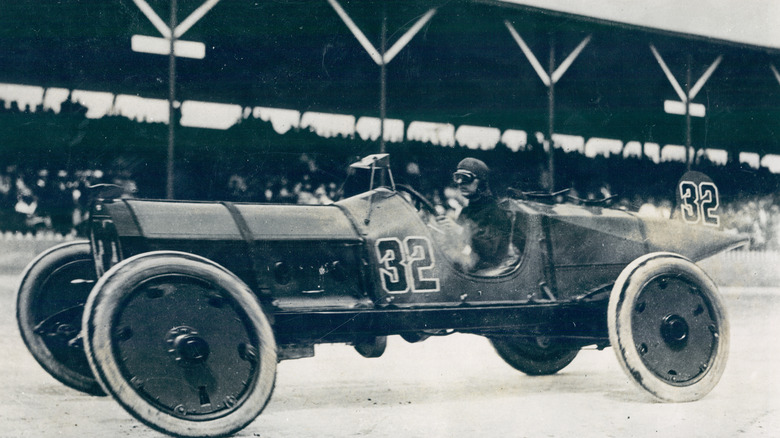

The very first Indianapolis 500 was, to say the least, very different from the race we know today, and have known for the past several decades. Instead of the 33-car field that has been a standard feature of the Indy 500 since 1934 (via Forbes), there were 40 cars at the starting line back in 1911. And the drivers weren't the only people in the vehicles, as all but one of the entries had "riding mechanics" sitting next to the drivers, as noted by Smithsonian Magazine. The only one-seater in the race, and therefore the only entry without a riding mechanic, was driven by a veteran racer named Ray Harroun, aka "The Little Professor." The 32-year-old Harroun was employed as an engineer for the Indianapolis-based Marmon Motor Car Company and only raced part-time. He did, however, set his share of over-the-road racing records in the early 1900s.

Harroun, who drove the No. 32 Marmon Wasp, only qualified at 28th, and being so far behind pole position, it would seem that he had his work cut out for him. But with co-driver Cyrus Patchke relieving him for 35 of 200 laps, Harroun and the Marmon Wasp led all but nine of the final 97 laps and won the 1911 Indianapolis 500. He finished the race in six hours, 42 minutes, and eight seconds, with an average speed of 74.602 mph.

The Marmon Wasp included a feature that remains in use to this day

As Ray Harroun worked for the same company that manufactured his Indianapolis 500-winning ride, his car came with an important innovation that remains a key feature of modern automobiles more than 100 years later. That feature, as explained by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway website, is the rear-view mirror, and while Harroun is not the only person credited for coming up with the idea, his use of a rear-view mirror on the Marmon Wasp is one of the first notable applications of the technology. Apparently, he was inspired to outfit the Wasp with a rear-view mirror during his time working as a chauffeur in Chicago, which was when he spotted a similar contraption being used on a horse-drawn taxi.

Given how riding mechanics served as an extra pair of eyes for the drivers they were riding with, Harroun didn't need anyone else to serve as a spotter while driving the Wasp at the Indy 500. As such, it made perfect sense that the vehicle was a one-seater, and the Wasp's lighter weight (aided by the fact that it carried only one person) is considered one of the main factors that helped Harroun win at Indianapolis and outclass the 39 other drivers who took part in the inaugural race.

The 1911 Indy 500 was Harroun's last major race

Ray Harroun was no stranger to winning at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway at the time he won the first Indy 500. Although statistics from the early years of auto racing in the U.S. are far from complete, Harroun won at least seven races at the now-iconic racetrack prior to his big win in 1911, per the IMS' official website. The 1911 Indianapolis 500 also happened to be his last hurrah of sorts as a race car driver, as it was his last major event before he transitioned into the next stage of his career in the racing scene. After winning his first — and only — Indy 500, Harroun took part in a much shorter (how about three miles?) race at the Fort Wayne Driving Park in September of that year.

That all said, Harroun had a pretty successful racing career, and had, in fact, finished as the top driver in the 1910 American Automobile Association National Driving Championship. Per Racing Reference, he also finished fourth in the AAA rankings despite only competing in one race — the Indy 500. However, it wasn't until 1927 that Harroun was retroactively awarded the 1910 championship. By that time, the Indy 500 was in its mid-teens, and Harroun was keeping a much lower profile than he did in the years immediately following his 1911 victory at the IMS.

Harroun kept innovating after winding down his career as a racer

Three years after he won the Indianapolis 500, Ray Harroun joined the Maxwell racing team, where he oversaw the program and came up with another noteworthy innovation to follow up the rear-view mirror of the No. 32 Marmon Wasp. According to his profile on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway website, Harroun developed a kerosene carburetion system that was so efficient that Maxwell driver Billy Carlson only needed 30 gallons of fuel to finish the 1915 Indy 500. He finished a respectable ninth place in a field of 24 cars but was the only Maxwell driver to reach the finish line. Tom Orr retired after 168 laps, while Eddie Rickenbacker — yes, the same famous World War I pilot — was out at the 103rd lap.

Aside from those advances, Harroun reduced pit times and improved durability with his pressed-steel wheels, which he introduced at a time when race car drivers were using wooden wheels. By the 1920s, most racing teams had followed his lead and become adopters of this technology (via The New York Times).

In 1917, Harroun tried his hand at manufacturing automobiles and founded the Michigan-based Harroun Motor Sales Corporation, which only lasted five years before it folded in 1922. Despite his seeming lack of success in that venture, he continued working as an automotive engineer and was also involved in the military space in a similar capacity, though he wasn't anywhere as visible as he used to be — except on certain occasions recognizing his historic victory at the inaugural Indianapolis 500.

Harroun and the Marmon Wasp remain historically significant

Given how he was the first driver — and the Marmon Wasp was the first car — to win the Indianapolis 500, Ray Harroun and his ride were back at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway at two milestone events. In 1937, ahead of the 25th edition of the Indy 500, Harroun drove a few laps in the Wasp. He then celebrated the 50th anniversary of his victory by doing the same prior to the 1961 race. Nine years prior to his second IMS return, he was among the 10 inaugural inductees to the American Auto Racing Hall of Fame. Harroun died on January 19, 1968, in Anderson, Indiana, exactly one week after his 89th birthday.

Although it is now being kept permanently at the IMS Hall of Fame Museum, the Marmon Wasp has occasionally been driven by auto racing legends in celebration of more recent Indy 500 milestones. Parnelli Jones, who won the 1963 Indy 500, drove it at the race's Centennial Edition in 2011, and the late Al Unser Sr. (pictured above) gave it a spin at the 100th iteration of the event in 2016.