Why The 1876 Presidential Election Was The Most Controversial In History

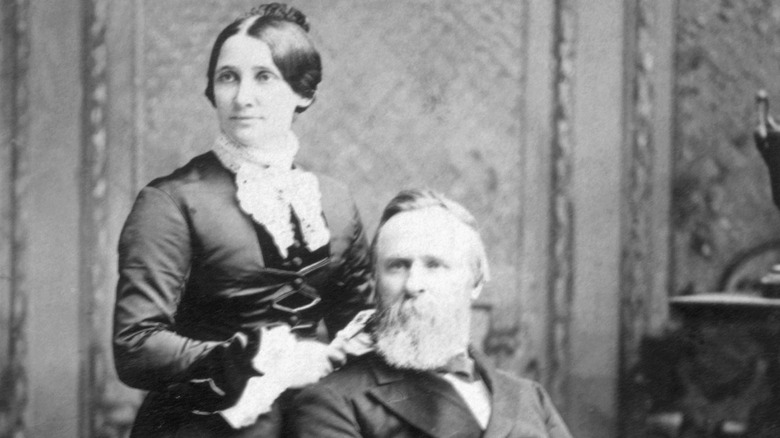

The 1876 disputed presidential election between Democrat Samuel J. Tilden (of New York) and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes (of Ohio) would become the most contentious in American history (via The Florida Historical Quarterly). For the second time in just over a decade, the United States was on the brink of governmental collapse. Why? According to election results, both of them had won.

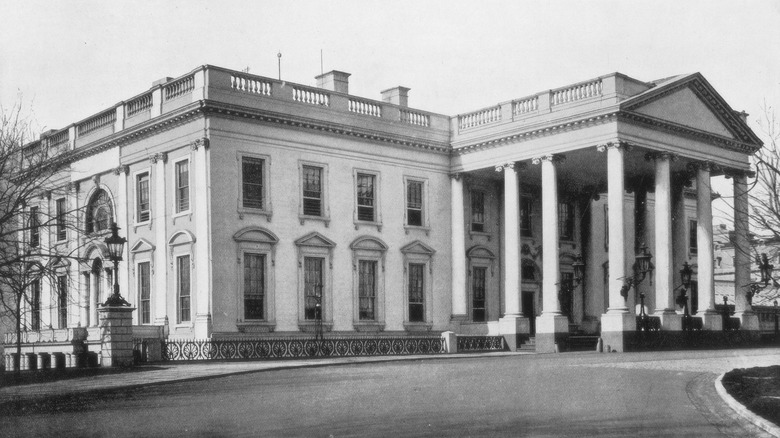

"On the day of the election, evade Grant's minions as much as you can, but let your unerring bullets pierce the breasts of ravenous carpet-baggers," read a confidential memo sent to top Democrats in Southern swing states. "Drive them with one swoop from the polls; and if necessary deluge your land with their blood." The memo, dated October 13, 1876, was titled "Carnival of Blood" (via Library of Congress), and it wasn't the only one like it. For the first time in years, Democrats had a real chance at winning a presidential election, and they knew it. Bitterly resentful toward Republicans for Reconstruction and the economic devastation of the post-Civil War South post-Civil, white Democrats were determined to reclaim the White House at any cost. Republicans, at any cost, were equally determined to keep it.

'Waving the bloody shirt'

In the weeks and months leading up to the presidential election of 1876, both parties whipped up public outrage to a fever pitch with press coverage, describing apocalyptic futures and secret plots wrought by the opposing candidate (via Harper's Weekly. They did not hesitate to accuse candidates of insanity, alcoholism, and even murder. During the 1876 presidential campaign (per Harper's Weekly) both candidates ran absolutely brutal "mudslinging" campaigns slandering opponents, with the press manufacturing a sense of dire urgency to whip up support — and for the most part, it worked.

While the Hayes and Tilden campaigns both played dirty, so did several states. Months before the election took place, many were already setting up systems to rig the results. Some counties set up alternating time blocks allotted for Democratic and Republican voters in advance, hoping to reduce the chance of violence between the opposing parties (via Florida Historical Quarterly).

In Florida, preemptive attempts to influence the election were already well underway. Similar events would play out in other Southern states. White merchants prioritized Democrats when granting credit or approving applications for rent. Florida Central Railroad Company handed out Democratic ballots to employees and kept a checklist of who had voted — non-voters would be fired (via Florida Historical Quarterly). Some counties had their polling places simply removed by opposing party officials — residents now would need to travel dozens of miles to cast their ballot, or otherwise would not be able to vote at all.

Fraud in Florida: The election was rigged before it started

To Southern Democrats, "Carnival of Blood" didn't sound so cartoonishly awful. Both South Carolina and Louisiana utilized white supremacist paramilitary groups, usually masquerading as "rifle clubs," to threaten, intimidate, and commit acts of violence against Black and white — but especially Black — Republicans (via Journal of Interdisciplinary History). In South Carolina, the Democratic candidate for governor, Wade Hampton, would even use one such paramilitary group, the Red Shirts, as his personal security at campaign events (via South Carolina Encyclopedia), effectively deploying them as a paramilitary wing of the Democratic party.

Robert Meacham, a half-Black Republican State Senator, was attacked about a week before the election by unidentified individuals who informed him he was "fired." Democrats said they knew nothing about the attack, and argued it had been conjured by Republicans as an excuse for violent acts they planned to commit on election day. Newspapers including the Tallahassee Journal urged Americans to go out and vote even if doing so might cost them their lives (via Florida Historical Quarterly).

Fraud in Florida: train wrecks, votes cast by children, stolen ballot boxes, quadruple ballots

On November 7, 1876, Election Day finally came and went. Almost immediately, both parties declared victory and accused the other of fraud (via Harper's Weekly). Allegations began appearing in partisan newspapers a few days later. Once again, rumors that would be absurd even by modern standards abounded. Some of these reports were, as one Tallahassee reporter described it, "destitute of truth." Others most certainly happened.

According to Florida Historical Quarterly, a coalition of more than 100 local Democrats in Hamilton County teamed up to steal a ballot box and "guarded" it from Republicans until November 13, when the county canvassing board would meet. Not to be outdone, Republicans in Jacksonville County reportedly stole a ballot box themselves and "corrected" the votes. In Leon County, one industrious superintendent concocted a plan to print a second set of ballots on thin pieces of paper, fold them inside the regular ballots, and thereby allow party members to vote multiple times for their candidate. (This plan was never executed, although it later was the cause of an indictment.)

One County judge won a Republican majority by simply discounting two counties' returns. The reason? He said he'd heard rumors of voter fraud. (This rhetoric would be repeated by officials in South Carolina, albeit to much darker and more violent results, per via Journal of Interdisciplinary History.) Fraud? Surely not in these United States.

The two governments of Louisiana, and chaos in South Carolina

Meanwhile in Louisiana, the situation was even worse. The Republican governor was trapped in the statehouse. The Democratic governor paraded troops through the main streets. That's right: There were two governors. Louisiana's Republican electoral board reportedly offered the Democratic National Committee a deal: they would certify Samuel J.Tilden the winner for a small fee of $1 million. According to Smithsonian's Gilbert King, the Democrats rejected the offer.

When both sides declared victory on election day, both governors took the oath of office separately. When Republicans locked Democrats out of the statehouse, the Democrats set up their own legislature. According to the Law Library of Louisiana, repeated calls for assistance to President Grant went unanswered for weeks, leaving the state government in chaos.

In South Carolina, both sides declared victory and accused the other of fraud (via Journal of Interdisciplinary History). The Democratic legislators also established their own parallel government. Both legislatures claimed they were the legitimate one. Both certified their own sets of results, and both swore in their own candidates.

Two parties, two winners, two governments: South Carolina and Louisiana

On the evening of the election, Samuel J. Tilden, the Democratic candidate from New York, was reported the winner of the popular vote. He'd also taken 184 electoral votes — just one shy of the number required to win the presidency — and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes had won 165. Tilden was announced the winner, and Hayes went to bed assuming he had lost (via Harper's Weekly).

But in Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida , Democrats and Republicans returned two separate sets of election results to Washington, D.C. (per American Presidency Project). Samuel J. Tilden had won. So had Rutherford B. Hayes. This presented a problem the federal government was not quite sure what to do with.

Due to a dispute over the eligibility of an elector, Oregon's final vote count was also left in stasis. In total, these four states had 20 electoral votes that were still undecided. If Hayes could secure those 20 votes from the contested states — and secure all of them — he could still win the presidency.

Technical difficulties still ongoing: Congress decides to do something

Awarding those votes to either candidate would prove an arduous affair that stretched on in proceedings for weeks. If Congress didn't figure out, as History Today notes, the outcome would likely be catastrophic: Samuel J. Tilden would come to D.C. on Inauguration Day, and both parties would swear in their candidates as the legitimate president. Yet much like the rest of the country, the United States Congress was still in a state of disarray. In mid- to late January, a representative finally proposed a bill to establish a commission to resolve the still-disputed election question.

After much fanfare, it was decided that the Electoral Commission would be comprised of five members of the Republican-dominated House, five members of the Democrat-dominated Senate, and five Supreme Court justices (via Smithsonian). Lawyers for both parties were present. Both Democrats and Republicans presented their sets of results and made the case that theirs were legitimate. Proceedings stretched on for weeks.

'Tilden or Blood'

With the election still hanging in the balance, state militias and military outfits began to assemble in contested states, according to Smithsonian's Gilbert King. Practice drills and military parades were conducted in preparation for the conflict to come should Congress fail. At the order of William Tecumseh Sherman (via Harper's Weekly), four artillery units were dispatched to Washington, D.C. President Grant's federal troops still guarded government buildings in Tallahassee, New Orleans, and Columbia. Louisiana and South Carolina were still living in near-wartime conditions in their state capitols, with Democrats and Republicans continuing to insist they were the legitimate winners of the vote. Democrats and Republicans in both states continued to operate parallel governments (via Harper's Weekly).

Across the entire nation, people congregated in the streets outside statehouses, party headquarters, and newspaper offices, awaiting news of something — anything — finally resolved. Gone was the highly-charged atmosphere of the election, and in its place emerged a deepening sense of hostility and doubt.There were serious, and well-founded, fears of an impending second civil war (via Smithsonian).

A crisis and a compromise in Congress

As the electoral commission began to award every set of disputed votes to Hayes (voting along partisan lines), the Democrats objected at every turn (via Harper's Weekly). Refusing to recognize these declarations as legitimate, Democrats introduced even more issues for Congress to resolve, objecting to nearly every decision their opponents made. Democrats objected to returns from Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island. One Democrat presented a new, second set of results for the vote from Vermont (via Harper's Weekly). Another objection was made to an elector in Wisconsin.

Democrats began to filibuster the proceedings, but when closed-door meetings between emissaries for both parties began at the Wormley Hotel in Washington, D.C., the Democrats mysteriously decided to budge.

The election dispute was not resolved until 4:10 a.m. on March 2, 1877 — just two days before the United States (sans president) would legally enter an interregnum (according to The New York Times) and three days before the presidential inauguration. All 20 disputed electoral votes were granted to Rutherford B. Hayes and certified by Congress. With 185 electoral votes, Rutherford B. Hayes was now the winner of the 1876 election — by exactly one vote.