Grover Cleveland Avoided The Civil War Through This Controversial Loophole

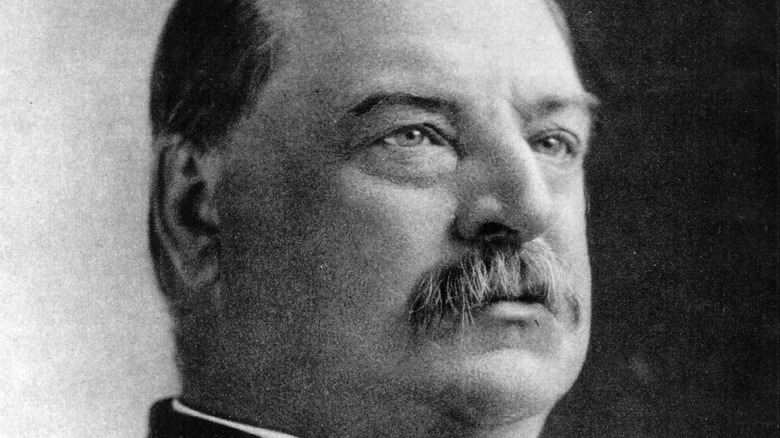

Grover Cleveland, the 22nd (and 24th) president prided himself on his reputation as an honest man, but a few of his once-scandalous misdeeds have survived along with him, still scandalizing someone somewhere to this day. Cleveland was discovered to have fathered an illegitimate child and accused of committing sexual assault (via History Net), but perhaps no incident from his past or present drew more criticism than 26-year-old Cleveland's refusal to fight in the Civil War. In a politically polarized climate only two decades since the most devastating domestic conflict in America's young history, his reputation was marred by the fact that in 1861, Grover Cleveland had dodged the draft.

While most of the nation was at war, in 1863 26-year-old Cleveland was working as a lawyer in Buffalo, New York. Relatively apathetic about the Union cause, Cleveland much preferred to practice law, dabble in politics, and continue life as usual rather than undergo the unpleasant business of enlisting. When the Civil War Draft Act was passed in 1863 and young Cleveland got drafted, he hired 32-year-old George Benninsky (or "Beniski," per National Archives), an undocumented Polish immigrant, to fight in his place, utilizing a controversial loophole in a controversial law (via "The President is A Sick Man").

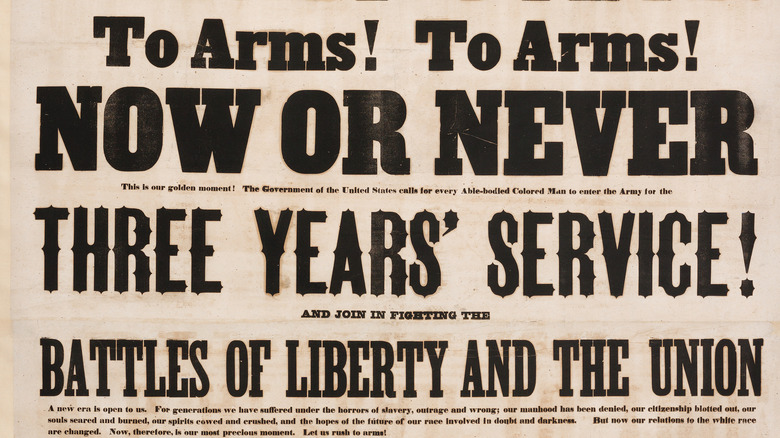

Rich Man's Battle, Poor Man's Fight

On March 3, 1863, Abe Lincoln signed the Enrollment Act (or Civil War Draft Act/Conscription Act) into law. The bill included a loophole: draftees could instead pay a substantial commutation fee of $300 (amounting to 75-120% of the average laborer or farmhand's annual income or otherwise hire a substitute (via "The President is A Sick Man") to face the mortal danger of the battlefield on their behalf.

Grover Cleveland was drafted the very first day the law went into effect (via "The Last Jeffersonian"). Like several other prominent figures of his day (including future founder of Standard Oil Company, John D. Rockefeller) who found themselves apathetic to the war cause, Cleveland had already decided he would rather pay than fight. When confronted with the issue later on in life, Cleveland would say that he was also the only member of his family with a sizable income (one of his brothers was already fighting, another brother would soon be called into battle as well, and a third brother was a Presbyterian minister with an income hardly comparable to Cleveland's sizable profits as a lawyer, per "Grover Cleveland"). He was also the primary breadwinner for his mother and two younger sisters. The war cause did not excite him. It was an obvious choice.

Grover Cleveland and George Beniski

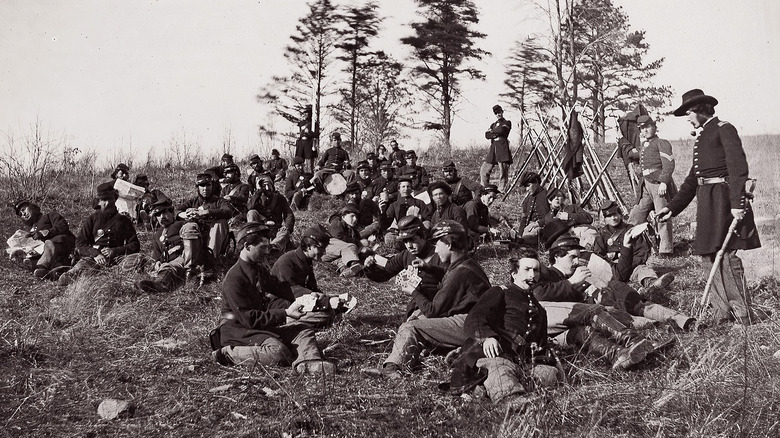

Short on cash, Grover Cleveland borrowed the money from his boss (District Attorney Torrance) and hired a friend of a friend to take his place. Cleveland paid George Benninsky $150 to enlist in the 76th New York Regiment in his place. Benninsky, an undocumented immigrant from Poland, likely had little choice but to take the gig. When criticized for hiring a substitute by opponents, Cleveland defended himself by arguing he could have used his power as a lawyer to conscript unpaid prison labor for free, but instead he hired Benninsky and paid him the going rate (via "The Last Jeffersonian," "The President is A Sick Man").

Cleveland's political opponents later spread a rumor that Benninsky had been horribly mutilated while fighting on his behalf, appealed to Cleveland for help after his injury, and was ruthlessly turned away to face a life of miserable disfigurement and destitution on his own (via "Grover Cleveland"). In actuality, George Benninsky had a fairly average if not comparably fortunate time in the Army, serving most of the war as an orderly at military hospitals after hurting his back at Rappahannock shortly after enlisting. As far as we know, he went on to live a normal life, most likely without realizing that the $150 he had earned would ensure his name lived down in history.