The Most Common Ways To Die In Ancient Egypt

Fun fact: while it was famed throughout the Mediterranean for its doctors, ancient Egypt was barely above the level of present-day first aid. Royals, with their access to better food and the best medical attention (such as it was) lived impressively long lives, but researchers Eike-Meinrad Winkler and Harald Wilfing determined that during dynastic times, the average life expectancy for everyday Egyptians was 19, while the mid-30s was the limit. If one was lucky enough to survive birth, there was a lifetime ahead of diseases that could not be cured, injuries that could not be treated, and circumstances that could not be controlled. Dying peacefully of old age was practically unheard of.

Medicine may have a long history, but "modern medicine," with immunizations, vaccines, x-rays, chemotherapy, and gene therapy, only began with the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. Ancient Egyptians depended on rudimentary skills as much as the body's resilience, meaning everything from disease to hitting your head carried serious risk.

Luckily for us, ancient Egypt, with its eons-long tradition of mummies, papyrus texts, and hieroglyphic records, gives researchers a unique opportunity to explore causes of death along the Nile ... the many, many causes. Read on to find how far medicine has come, but also how far it has to go.

Schistosomiasis

No matter how obscure, some ancient disease accounts are so detailed that modern doctors know exactly the cause. When Egyptian papyri describe a grossly protruding belly and Herodotus adds that Egypt was a land where men menstruate (he was describing blood in the urine), archeologists and pathologists both know schistosomiasis has long been a problem for the Nile valley.

The CDC describes schistosomiasis as being caused by parasitic worms that first infest freshwater snails, then move to humans. Children are particularly hard-hit, suffering scarring and inflammation of the intestine, liver, and bladder, and with long-term victims developing anemia, malnutrition, and learning difficulties. In extreme cases, worm eggs can be swept into the brain or spinal cord, setting off paralysis or seizures. Inflammation of the liver can cause it to bulge, distending the abdomen; likewise, inflammation of the bladder can be associated with blood in the urine (via Healthline).

Ancient Egyptians knew fresh water held dangers. A Nature study mentions what Egyptians called "aaa," a condition mirroring modern schistosomiasis, and describes fishermen and other water workers taking protective measures such as penile sheaths. Mummies dating back 5,000 years show evidence of the condition, and to this day it still lingers in Nile waters even after eradication campaigns. Ancient records do not record mortality numbers from schistosomiasis, but a 2013 study notes that 200,000 deaths per year are still associated with the disease.

Smallpox

While ancient Egypt had natural barriers on all sides, it did not exist in a vacuum. The civilization still contended with maladies that befell human populations the world over. Few claimed more lives than smallpox.

The World Health Organization dubs smallpox "as one of the most devastating diseases known to humanity" responsible for millions of deaths. Ancient Egypt was not spared; National Geographic postulates the Nile Valley was, in fact, the origin of the virus 3,000 years ago. The mummy of Pharaoh Ramesses V (dying in around 1145 B.C.) shows pockmarks characteristic of the disease, possibly dying from it. He wasn't alone; an article at Science notes that the virus struck the population regardless of class or age. Several mummies bear the tell-tale scars, including that of a child.

According to the CDC, three out of 10 people who contracted smallpox died; a disease with a 30% mortality rate would have devastated ancient Egypt (and its contemporaries). Those that survived were almost always scarred, sometimes severely. It was only after a massive vaccine campaign starting in 1959 that the virus came under control, and not until 1980 that authorities declared smallpox effectively extinct. But ancient Egyptians had to suffer through epidemic after epidemic. But when life gives you lemons, make lemonade: the Hittites, rivals of the pharaohs, accused Egyptian armies of using smallpox as a bioweapon.

Famine

In 1906, journalist Alfred Henry Lewis stated, "There are only nine meals between mankind and anarchy." The pharaohs knew this far earlier, however. Without the Nile, Egypt dies. Its annual floods provide both water and new soil, but the river is not foolproof. Described by EgyptToday, the aptly named "Famine Stela" tells of a devastating seven-year famine in the reign of King Djozer during the Third Dynasty around 2700 B.C. The Nile floods failed and a domino line of fallout hit the kingdom; when the crops withered, food stores were emptied. In the face of hungry crowds, temples and shrines shut their doors. Starving, people turned to robbery and society broke down. It was only when Djozer appealed to the god Khmun that the floods returned.

But New Scientist tells of another drought-famine that hit in 2180 B.C. so massive it brought down the Old Kingdom and the age of the pyramid builders. The Bible records several famines, including the famous Famine of Joseph in Genesis 47:13-27 that hit not only Egypt, but also ancient Israel. The passage describes how Egypt resorted to grain allotments to cope, but also how Joseph's people gave into servitude under the pharaohs for food. Several mummies show signs of malnutrition.

Famines were so prevalent in Egyptian history, they even made news when they didn't happen; EgyptToday tells of an inscription in a 12th Dynasty tomb taking pains to describe the tenure of a king whose reign never saw a famine.

Infant mortality

Exact rates of infant deaths in ancient Egypt are hard to come by, but a 2013 study found that by the 1700s, an age whose medical establishment should have progressed significantly beyond that of pharaonic times, the world infant mortality rate nevertheless hung around a whopping 43%, with numbers coming down only after World War II. PBS states that even in a good year — and even in early industrial society — about 200 out of 1000 live births died.

Regarding old Egypt, an article at Ancient Orgins says that it was considered a divine blessing if a child was alive a year after its birth, and a "double joy" if adulthood was reached. Numerous graves containing children and babies dot the Nile Valley. One source notes that child death peaked at around age 4, the age when children were weaned and switched to solid food (and thus introduced to new pathogens). If a child reached five years of age, the risk of early death receded.

High infant mortality may explain odd perinatal rituals all over the Mediterranean: a dead child was not mourned if under a year old in Rome; the Spartan Greeks killed infants outright if born sickly; and in the Bible, Leviticus 27:6 states a baby was of no worth until a month old.

Maternal death

A 2018 article in National Geographic describes the very rare discovery of an ancient Egyptian grave containing a pregnant woman with the child wedged in the birth canal. The hips of the mother were misaligned, causing the baby to become stuck and most likely precipitating the death of both. The burial site was 3,700 years old, and it's a grim testament to the reality that women dying in childbirth is nothing new.

Without modern medical procedures, a study from the International Social Science Review concludes the rate of maternal death stemming directly from childbirth in the ancient world as a whole stood at around 14%, with hemorrhage, pelvic deformity, and eclampsia as three named causes. Another research paper notes that maternal mortality was such a threat that often whole households of women would either act as midwives or assist one, and adds that at least two papyri give specific instructions on assisting the birth of a child and how to address issues that may arise.

Even today, 800 women a year in America die either from childbirth outright or from complications within 42 days after delivery. Scribes in ancient Egypt did not record maternal mortality of the nation, but in an age when sanitation was basic and obstetrics was fraught with superstition, it can be assumed that death was something expectant mothers faced with every pregnancy.

Malaria

The toxic romance between humanity and malaria began 10,000 years ago (per the National Library of Medicine) when humanity shifted from nomadism to settled agriculture. A bacterial parasitic infection spread via mosquitoes, malaria depends on water for survival. Like the Nile. Symptoms include a flu-like malaise, chills, and diarrhea, but lack of proper treatment can lead to far more severe conditions including anemia, kidney failure, seizures, and coma. While malaria is not invariably fatal, the World Health Organization nevertheless records 627,000 deaths yearly.

Per NBC, experts, however, believe that in ancient Egypt, when there was no effective treatment (for the bacteria, the mosquitoes, or the water), malaria was epidemic. More, it was present very early in the civilization's history; a study from the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases found malaria in mummies from 4,000 years ago. And not just any mummies: according to National Geographic, the already famously sickly Tutankhamun (aka King Tut) had the parasite when he died, proving that malaria scythed through the Egyptian population regardless of class. A study by the University of Arkansas found that in just the city of Amarna alone, 50% of the ancient inhabitants suffered from the disease. NBC further reports malaria was so virulent, its presence as a unique malady was recorded in papyri and commented on by historians.

Malaria plagued more than the Nile Valley; Greece, Rome, and Israel all suffered. For Egypt, malaria remains a tenacious problem; the CDC warned of an outbreak that lasted until 2014.

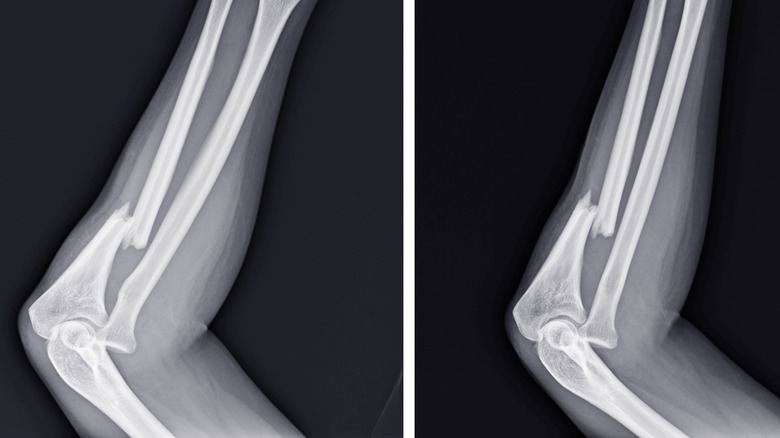

Injury

Whether by war or accidents, ancient Egyptians died from injury like anybody else. In what must have made Egyptologists positively flip, ancient doctors were scrupulous in their care and even took notes, some of which survived to the present day. One particular papyrus lists treatment for 48 traumas: 27 head injuries, six to the throat, two to the clavicle, three to the arm, eight to the sternum and ribs, one to the shoulder, and another to the spine. Clearly, ancient Egyptians were getting hurt.

Archeological evidence agrees. New Scientist notes several bodies of pyramid workers bear broken limbs, damaged spines, and splintered feet; AP reports 12 skeletons were found with splints present, while a Deseret News release describes six skeletons with fatal wounds. And these were all peace-time injuries.

War was a whole other ball game. According to the BBC, the mummies of 60 male archers dating to the Middle Kingdom clearly show damage from head injuries caused by fighting: axe wounds, spear piercings, and arrow damage. And where mummy-evidence falls flat, ancient accounts pick up: Egypt got into some history-making battles, with casualties to boot. Arguably the biggest was the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites in 1274 B.C. Exact troop numbers were not recorded (experts know at least 20,000 infantry and 2,000 chariots were on the field for the Egyptians), but History Net does say that there were significant losses. Ironically, nobody won Kadesh; it was a stalemate.

Tuberculosis

Spread through coughing, tuberculosis (also known as "consumption") is a highly infectious bacterial disease of the lungs that killed 1.5 million people in 2020 alone, but the CDC notes the affliction has lurked in the human lineage since 9,000 years ago. One of the most common, and dramatic, symptoms is coughing up blood, but not content with reaming the lungs, tuberculosis can spread to other parts of the body including the spine. This condition, called Pott's disease, occurs when the afflicted vertebrae snap forward to form a hunchback.

According to the Museum of Healthcare, the history of tuberculous in the Nile Valley stretches back to 5,500 years ago: mummies from 3,500 years ago bear the characteristic lesions, papyri detail symptoms reminiscent of condition, and hieroglyphic inscriptions show people with what is probably Pott's disease. Tuberculosis was so prevalent that it may have been a major cause of death among the population.

Perhaps ancient Egypt's most famous victim to tuberculosis is a woman named Irtyersenu. A paper published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences describes her as 50 years old and dying in around 600 B.C. Intact enough for doctors to perform an autopsy, her body was found riddled with the bacteria that causes tuberculosis. While she suffered from other conditions at the time of her death, the medical team is confident the disease was the major contributor to her passing.

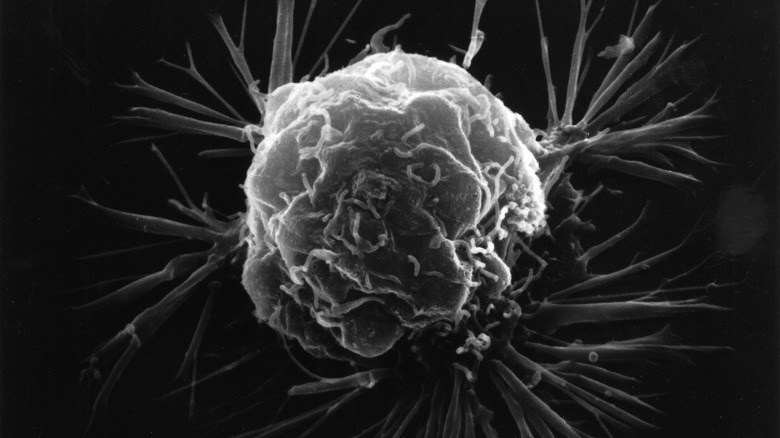

Cancer

The history of cancer goes so far back, it actually extends beyond our species; Raconteur reports that dinosaurs had it. A BBC article relates how the rib of a Neanderthal from 120,000 years ago has the tell-tale signs of a bone tumor. By the time ancient Egypt arose, around 3100 B.C., cancer was old hat.

In fact, according to Cancer.org, the condition is one of the oldest attested sicknesses in ancient Egyptian literature; its description in records dated to 3000 B.C., just a century after the civilization's foundation. This means cancer was stalking the people of the Nile Valley practically from the start. Ancient doctors were realists — when they saw cancer for what it was, they knew there was no cure. They simply wrote, and presumably told their patients, that "there is no treatment." It wasn't until 1956 that cancer was definitively cured for the first time.

For the ancient Egyptians (and anybody else in the world at the time) cancer meant a slow, painful, and lingering death. The only silver lining is that in an age where most people died young, cancer, usually a disease of the elderly, did not have time to develop. But this was far from an absolute: Science tells of an ancient Egyptian man, known only as "M1," who beat the odds and managed to live to 60, but paid for the honor dearly. Living 2,250 years ago, M1 died from prostate cancer.

Tularemia

In 1715 B.C., an epidemic devastated Egypt, but experts were not sure what the disease was. National Geographic suggested an early form of bubonic plague, but typhus and typhoid syndrome were also candidates. Now medical science suspects it was a little-discussed bacterial infection called tularemia. Unfortunately for sufferers then and epidemiologists now, the disease can appear as bubonic plague, typhus, and typhoid all at the same time.

The identification of tularemia came about not by whom it killed, but by whom it didn't. According to an article published by Medical Hypothesis, records indicate that the disease first appeared in the Nile delta port of Avaris and ripped through the Egyptians, but not a population of Hebrews tending their flocks outside the city walls. Tularemia, also known as rabbit fever, spreads by ticks, deer flies, and infected animals — something with which the herding Hebrews experienced every day. This is key, because the Medical Hypothesis study proposes the Hebrews had long been exposed to avirulent strains of tularemia via their animals and that these low-level infections created a ready-made immunity by the time the more virulent version hit. The city dwellers of Avaris had no such protections and quickly succumbed, as did the rest of Egypt.

The death toll of the 1715 B.C. outbreak is not known, but the ramifications for a country with just 2 million people were staggering. The golden age of the Middle Kingdom crashed, the turbulent Second Intermediate Period began, and Egypt fractured.

Paracitic anemia

The ancient Egyptians were well aware of anemia as a specific malady; another name for the condition, in fact, is Egyptian chlorosis. As described by the Mayo Clinic, anemia of any sort occurs when the blood lacks adequate healthy red blood cells, which themselves are the medium with which the body disperses oxygen. Per the CDC, the condition can arise from hookworms, an intestinal parasite that spreads when a person walks barefoot across soil infected via fecal deposition. The larvae then burrow through the skin before latching to the small intestine to feed. With so much of the population working in agriculture, and where the fields were sometimes tilled with feces, ancient Egypt would be a prime target.

That said, anemia by itself rarely kills (1.7 deaths out of a thousand in the U.S. today), but it can severely weaken the body right down to the bones and can exacerbate other conditions. According to LiveScience, a mummified head of a woman, nicknamed Meritamum, shows her skull was extremely porous, a tell-tell sign of severe anemia. She also suffered tooth abscesses, and the two conditions would have likely left the woman lethargic, pale, and in constant pain. Without the rest of the body, it is unclear what killed Meritamun, but her skull alone suggests her body could have given out from too many infections.

Dated to circa 1550 B.C., the Ebers Papyrus contains what medical professionals now recognize as descriptions of hookworm infections.

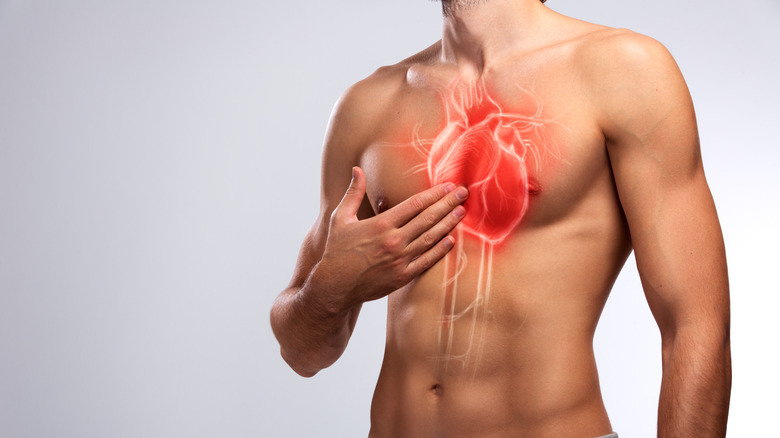

Atherosclerosis

Let's face it: if you know you are probably going to die young, you may as well enjoy what time you have. And if the clogged arteries of ancient Egyptian mummies are any clue, the people of the Nile Valley ate, drank, and lived life to the fullest for as long as they could.

In fact, as ABC reports, experts were left flabbergasted at just how many ancient Egyptians suffered from some sort of cardiovascular disease; in a test of the 22 mummies housed at the Egyptian National Museum of Antiquities in Cairo, 10 had ticking time bombs in their heart. Other studies sing the same song — a paper published by the National Institutes of Health, 20 out of a selection of 52 mummies had some kind of cardiovascular condition; another notes that Pharaoh Merenptah, who died in the year 1203 B.C., had atherosclerosis and adds that of the 16 mummies in the control group, nine had a similar condition. If these examples are emblematic of the population, it can be extrapolated that nearly half of the ancient Egyptian population had a hardening of the arteries at the time of death.

According to John Hopkins Medicine, atherosclerosis is a build-up of fatty substances, cholesterol, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin due to, among other things, a high-fat diet. The accumulation thickens and stiffens the arteries, restricting blood flow. That, in turn, can lead to a heart attack.