The Assassination Of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Explained

World War I was brewing long before 1914. Per History, imperial ambitions fueled by the Industrial Revolution drove the great powers of Europe into competition for resources and military superiority. One nation's fears and suspicions of another would compel them to join alliances designed to check each other's potential aggression. The rise of nationalism during the Victorian era only further fueled tensions on the continent.

If any one event launched the war, however, it was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. The Austro-Hungarian empire's instability and position within the tangled alliances of the day made such a high-profile murder ripe fodder for the warmongers in Europe. They dreamed of a battle that would grow their empires. Instead, four years of butchery re-drew Europe's borders and cost several monarchs their crowns, including those of Austria and Hungary.

Like the war itself, the circumstances that made Archduke Ferdinand's death so consequential stretch back long before the assassination. Let's try and untangle the events and timeline of that fateful act.

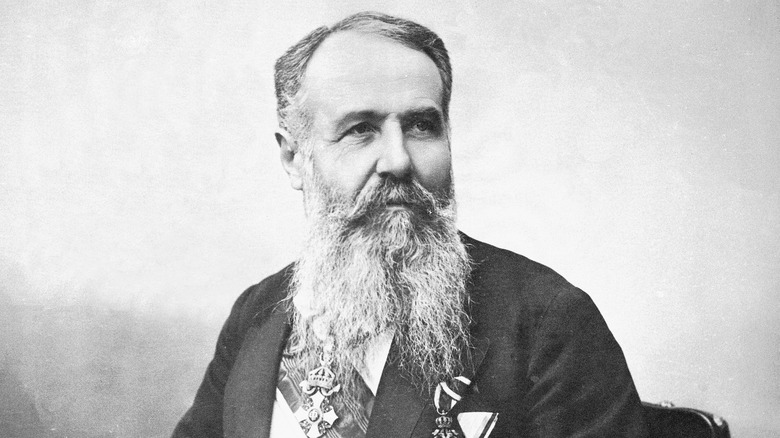

Franz Ferdinand, The Unwanted Heir

It is easy, perhaps, to imagine that anyone whose death was so consequential must have been a beloved figure. Yet Franz Ferdinand was not popular as an heir. He was the nephew of Emperor Franz Joseph I, named successor to the throne after the suicide of his cousin Rudolph in 1889 (via Biography). Almost at once, ruler and heir came into conflict.

Among their more personal disputes was over who Franz Ferdinand would marry. He fell deeply in love with Countess Sophia Chotek, of noble but not royal lineage. Membership to a reigning dynasty (or at least a formerly enthroned one) was required of any spouse to the emperor's heir, but Ferdinand refused to forsake Sophia. In turn, Joseph refused to consent to their marriage. Only after the intervention of fellow monarchs and the pope did the emperor relent. Even then, he stipulated that it was to be a morganatic marriage, with Sophia and their children denied any rights to the crowns of Austria and Hungary.

Even without domestic strife, Ferdinand was often at odds with his uncle. The World of the Habsburgs describes their very different characters: Ferdinand was impulsive and often ill-tempered, while Joseph was extremely reserved. In matters of politics and governance, Joseph clung to his throne and the state of his court, while Ferdinand — despite undemocratic and reactionary tendencies — prepared for significant reforms upon his succession.

Tensions Within The Empire

The throne Franz Ferdinand was to inherit had long been troubled. According to History Hit, the Austrian Empire was a multinational entity comprised of the territory of 14 modern states. The data from the 1910 census of the empire (per The World of the Habsburgs) indicates at least 10 languages had significant usage. Such a nation inevitably struggled to forge a unified identity and had a particular vulnerability to the tide of nationalism that began in the 19th century.

Nationalist sentiment had already forced a significant compromise upon the empire well before Franz Ferdinand became heir. In 1867, it was reorganized into the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary (per Britannica). But this arrangement left most of the empire's nationalities denied the privileges and authority granted to the German Austrians and the Hungarians, an inequality Emperor Franz Joseph recognized but failed to fully comprehend or alleviate. The Slavic peoples in the southern "states" particularly resented being ruled by Hungary, and the latter's Magyarization policy exacerbated tensions at home and abroad.

The Serbian Problem

If nationalism threatened the Austro-Hungarian empire from within, it also emboldened its international rivals. Among the most vexing of these was the Kingdom of Serbia. According to Britannica, the two nations had been at odds since the mid-1800s when a series of wars and treaties left significant Serb populations under an Austrian protectorate. A secret agreement by King Milan I of Serbia with Austria alleviated tensions somewhat, but as detailed by Professor Vincent Ferraro of Holyoake College, a 1903 coup greatly reduced Austro-Hungarian influence in the country.

The very existence of Serbia was considered dangerous to Austria-Hungary, according to History Hit. In a climate of growing nationalism, a Slavic state in the Balkans was an attractive lure for those Slavs living within Austria's borders. Should Serbia acquire them, or if they should successfully break away to join with Serbia, then all the empire's nationalities might follow suit. Such a fear led some authorities — including chief of the Austrian General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf — to agitate for preemptive war.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

In the late 19th century, the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina were highly coveted. The Ottoman Empire officially held them, Austria-Hungary and Serbia both wanted them, and the largely Slavic populations within them held dreams of independence. As a temporary measure to maintain peace against ambition, the Congress of Berlin in 1878 made the provinces protectorates of Austria-Hungary while leaving them within the Ottoman Empire (per History).

By 1908, however, the Ottoman Empire was shaken by the Young Turk Revolution, and Austria's rival in the Balkans, Russia, was still hobbled by its own revolution and its loss in the Russo-Japanese war of 1905. Seizing an opportunity to expand its territory, Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina. While an effort was made to come to an understanding about the annexation beforehand (per Britannica), it managed to upset Russia, Serbia, and Slavic movements throughout all of Europe. War might have broken out in 1909 — with Germany pledging to support even a war of aggression by Austria to retain its new territories — except that Russia reluctantly accepted the annexation when its ally France proved noncommittal about involving itself in a conflict over the Balkans.

Opposition to the annexation didn't only come from beyond Austria's borders. Though he had no personal sympathy for the Serbs, Franz Ferdinand believed that annexing Bosnia and Herzegovina would only worsen the ongoing tensions with the Slavic peoples of the empire (via History). But his opposition went unheeded.

Franz Ferdinand Had Solutions ...

Despite the ongoing troubles of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Joseph did not involve his heir in matters of state. According to The World of the Habsburgs, he worried that Franz Ferdinand was counting the minutes to Franz Joseph's death. Even without such suspicions, the emperor felt that an heir's duty was to quietly await his turn. But Ferdinand was of a different mind and began to prepare himself for rule by gathering advisors to function as a pseudo-shadow government.

The question of Slavic nationalism received considerable thought from Ferdinand. At one point, he mulled resolving it by transforming the dual monarchy into a triple monarchy (per Biography). Trialism, as this approach became known, would have created a third state centered around Croatia, encompassing all the southern Slavic peoples (via The World of the Habsburgs). But a triple monarchy would be complicated by tensions between the Austrians and the Hungarians, with Croatia caught between their disputes and conducting its own with Hungary.

Another answer to the Slav question Ferdinand entertained was moving Austria to a federal model. According to Almost History, this plan — dubbed the "United States of Greater Austria" — would reorganize the empire into 16 states. The borders were guided by language and ethnicity to grant all major groups representation under the monarchy. But despite Franz Ferdinand's support, the tricky relationships among the various peoples of the Austro-Hungarian empire made its reorganization a tall order even before World War I.

... But He Faced Stiff Opposition

In everything from his marriage to his plans to reform Austria-Hungary upon succession, Franz Ferdinand ran up against his uncle Franz Joseph and the members of his court and government. "He was prepared to rock a lot of boats," said historian Gary B. Cohen (via PBS), boats that weren't eager to be shaken. It wasn't only the aging emperor who resisted his heir's proposals either.

The one opportunity that Franz Ferdinand had before his death to enact some tangible influence on policy was in the army. According to The Irish Times, he achieved promotion to inspector general in 1896. In that position, he pushed for an army more dedicated to defense at home than interventions abroad. This put him in fierce opposition with chief of the Austrian General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf, who advocated for taking the fight to Serbia well before 1914. The Irish Times notes the great irony that it was Ferdinand's assassination that gave Hötzendorf his wish.

Austrian Reform Threatened Serbian Nationalism

Franz Ferdinand's proposals for granting the Slavic peoples of Austria-Hungary greater autonomy might have endeared him to them. Instead, they made the heir as unpopular with certain nationalist groups and with Serbia as he was within the emperor's court. According to The World of the Habsburgs, the perception within Serbia was that any friendly gesture from the Austrian throne would interfere with their own ambitions for the Balkans.

Fears of what Ferdinand's proposed reforms might mean ran even deeper outside government circles, per the National World War I Museum and Memorial. The society of the Black Hand, practitioners of anti-Austrian propaganda and violent political campaigns, worried that such a monarch might threaten the independence of Serbia as a nation. The Black Hand's activities outside of Serbia were most concentrated in the southern provinces controlled by Austria-Hungary, and it was from one of these provinces — Bosnia — that they found young men eager to kill the archduke.

Why Was Franz Ferdinand In Bosnia?

The Austro-Hungarian army prepared to run a number of military exercises in the province of Bosnia during the summer of 1914 (per History). As heir apparent and inspector general of the army, Franz Ferdinand was to review the exercises. Though the event was set to take place in June, preparations began well ahead of time, and neither the government nor the press was inclined toward secrecy about it. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, Ferdinand's visit was first announced in March. Not only that, but the local newspapers in Bosnia also detailed the archduke's travel itinerary for June 28. If anyone had designs on harming Ferdinand, they had all the information they needed.

Revolutionary movement Young Bosnia made good use of the available details of the trip to plot Franz Ferdinand's assassination. Word of their plot did not escape notice in neighboring Serbia, where prime minister Nikola Pašić feared both the consequences for Serbia of a successful assassination and the consequences for himself for publicly revealing the conspiracy. Instead, he passed along an indirect, opaque message to the Austrian government that never reached Franz Ferdinand's ears.

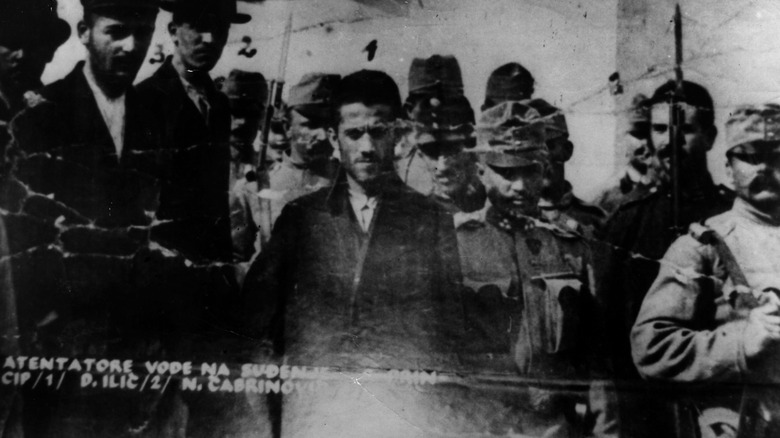

The Archduke's Assassins

Franz Ferdinand's assassins were waiting for him even before he arrived in Bosnia, according to The Globe and Mail. The pivotal member of Young Bosnia was Gavrilo Princip, a youth from a poor peasant family swept up in the tide of nationalism. Attempted and successful assassinations of royalty and government officials were not uncommon at the time and provided an example for such a radicalized young man.

Just how to describe Princip and his fellow Young Bosnians has vexed historians, as detailed by The Guardian. Depending on who writes the history books and where and when they do the writing, Young Bosnia is named a terrorist group or a band of heroes. Britannica and History describe the training Princip received as terrorism. His teachers were the Black Hand, formally named "Union or Death" in reference to the cause of a united Slavic state in the Balkans. Between his schooling in the arts of political violence and his commitment to the nationalist cause, Princip became convinced that killing a member of the Austrian elite was the first step to Slavic liberation. Franz Ferdinand's potential to improve the situation for Slavs within the empire made him an ideal target.

Inauspicious Timing

Almost from the beginning, Franz Ferdinand's visit to Bosnia seemed destined for misfortune. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the ongoing tensions caused by Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina meant that anti-Austrian sentiment was high in the province. Warnings about potential violence were indirect and ignored. And the date set for Ferdinand's visit, June 28, happened to be St. Vitus Day. On that day in 1389, Serbia fell to the Ottoman Empire, and the holiday has been marked by the Serbian people since as a remembrance of sacrifice and resistance — and there was a strong Serbian element in Bosnia.

June 28 was also an unhappy anniversary for Franz Ferdinand himself. On that day in 1900, he paid for his marriage to Countess Sophia Chotek by signing away his children's inheritance. The oath of renunciation demanded by Emperor Franz Joseph took Ferdinand and Sophia's children out of the line of succession and denied Sophia the same rank as her husband. In most public functions, protocol dictated that she be consequently separated from Ferdinand.

Protocol was not so strict away from the Austrian capital of Vienna, however. Suzanne Lynch in The Irish Times speculates that this may have given the trip an appeal to the ducal couple, in spite of the danger: Sophia would be able to accompany her husband on the trip and be at his side for it.

The Assassination Almost Failed ...

Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia departed for Bosnia on June 23, 1914. Upon their arrival, the first two days of their visit passed without incident (via History). While Franz Ferdinand reviewed troops and Sophia visited children, Gavrilo Princip and his fellow Young Bosnians finalized their plans to kill the archduke, making use of the pre-published details of his route through the capital city of Sarajevo on St. Vitus Day. The Black Hand had provided them with arms, including bombs, as well as cyanide pills. One of their number, Nedeljko Cabrinovic, was to take up a position on the main avenue with one of the bombs while the other six members spread out along the path.

Security for the motorcade was light on June 28 when Ferdinand and Sophia began their procession through Sarajevo. Still, luck seemed to favor the archduke at first. Cabrinovic hurled his bomb at Ferdinand's car, but it bounced off the roof without any damage to Ferdinand or Sophia. Those in the next car weren't so fortunate, as they caught the blast when the bomb rolled under them. Rather than use his cyanide, Cabrinovic made for the Miljacka river to drown himself but was intercepted. His attempt on the archduke's life didn't even stop Ferdinand from continuing on with his itinerary for the day. Two more of his would-be assassins, having caught sight of their target, hesitated at their chance and let him pass by.

... Until The Killer Received A Second Chance

The initial failure of Young Bosnia's dreams of political assassination left its remaining members despondent after Nedeljko Cabrinovic's arrest. Legend has it that Gavrilo Princip, after learning of the missed chance, retreated to Moritz Schiller's delicatessen to comfort himself with a sandwich. Mike Dash, writing for the Smithsonian, dispels the legend but confirms that Princip was in the vicinity of Schiller's. The deli was on the original route designed for Franz Ferdinand's motorcade.

From a position near Schiller's, Princip and Ferdinand should never have crossed paths after the first assassination attempt. Per History, after reaching city hall, Ferdinand decided to visit the hospital where those wounded by Cabrinovic's bomb were being cared for. He and Sophia set out again along what should have been a new route, but poor communication sent the motorcade down the originally intended path. As they worked to turn around, the archduke's car directly entered Princip's line of fire.

Luck might have been on Ferdinand's side one more time that day. In another Smithsonian article, Dash writes that the crowd was so dense that Princip couldn't make use of the bomb he had on him, leaving him only his gun. Princip later testified that he didn't aim or even turn his head, only firing toward the archduke's car. His blind shots managed to catch Ferdinand in the throat and Sophia in the stomach. Both died within minutes of the attack.

Youth Saved The Killer

"Sophie, Sophie, don't die," Franz Ferdinand begged his wife after he was shot (per History). "Stay alive for our children." His pleas were nothing against the fatal stomach wound Sophia took in the attack; their children would be orphaned. Yet the youth of assassin Gavrilo Princip saved his own life.

Taken into custody, Princip made no attempt to deny his guilt but insisted that he had only meant to shoot Ferdinand, not Sophia. Though his crime was not only murder but also the assassination of the heir apparent, Austrian law did not allow for the death penalty to be sentenced to anyone under the age of 20. Princip was just three weeks shy of his 20th birthday, so was instead given 20 years in prison. According to Britannica, it was the maximum sentence allowed for his age.

Princip didn't live to carry out his full sentence. Tuberculosis, which he may have already had before his arrest, cost him an arm. While recovering in the prison hospital, he passed away in April 1918. He was only 23 when he died. Princip's crime triggered a war that savaged all of Europe, but according to The Globe and Mail, he never showed signs of regret.

How Involved Was Serbia?

While Gavrilo Princip undeniably took Franz Ferdinand's wife, just how wide the conspiracy against the archduke stretched remains less certain. Princip and his men insisted that the plan was theirs, but they had received support from the Black Hand of neighboring Serbia, per Paul Miller-Melamed in The Washington Post. The Austro-Hungarian government wanted to know if their rival power had been complicit in the assassination (via The Irish Times).

The Black Hand was no secret society. Its leader was also the head of military intelligence for Serbia, Dragutin Dimitrijevic, and it operated in public view. Prime Minister Nikola Pašić's unheeded warning to the Austrian government shows he had at least some knowledge of the plot. When Austria finally issued a response to the murder, it plainly accused Serbia of abetting the actions of groups like the Black Hand.

Miller-Melamed argues for a smaller conspiracy. Dimitrijevic, better known as Apis, was no friend to Pašić. He and the Black Hand attempted a military takeover of the government in 1914 that was only foiled by international efforts. Austria's own intelligence agencies suggested that the Black Hand was a more immediate threat to Serbia itself than the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Apis may not have wanted the assassination to succeed at all, hoping only that the attempt would anger Austria enough to lobby for Pašić's ouster. The risk eventually led Apis to call off the effort — but not in time to stop it.