What Victorian Aristocrats Typically Ate In A Day

The Victorian era was one of massive change for people living in Britain and across the world. The Industrial Revolution upended traditional work, while advances like electricity and more educational opportunities for women pushed the scientific and social order into new realms.

That sort of change extended into even the most seemingly mundane places: the kitchen. While there were still an unfortunate number of bland boiled dishes, as NPR notes, there were cooks and diners who were willing to push the envelope. But, as much as things were shifting, there was still the social hierarchy to mind. The truth is that, for much of the Victorian period, the food eaten by aristocrats was far more diverse and just plain expensive than what was afforded to everyone else.

A glimpse into the day-to-day life of Victorian aristocrats might show some crowing about simple, hearty meals that were nonetheless served in fine dining rooms on one's country estate (and with luxe ingredients, no less). Others would routinely indulge in the complex social ritual of a multi-course dinner that naturally included opportunities to show off the skill of the family's hired chef, not to mention the sort of money necessary to put certain foods on the table. As it turns out, a menu can tell you far more than what's for dinner. To learn more about the complex, shifting world of 19th century Britain and beyond, here's a glimpse at what Victorian aristocrats typically ate in a day.

Breakfast could be pretty informal no matter who you were

Many of our modern ideas surrounding high-class Victorian meal times seem to involve a certain level of formality. You know the drill, especially if you've indulged in some period dramas courtesy of PBS or the BBC: dressing up in restrictive clothing, doing one's hair (or having your maid do it for you), and dining on the most delicate and rarefied of foods served on silver and fine china. But, as it turns out, even Victorian aristos couldn't be bothered to dress up for every meal of the day.

According to "Food and Cooking in Victorian England," breakfast was a simple affair pretty much wherever you were dining, though the rich person's definition of "shabby" morning clothes was probably markedly different from those of a common laborer. If you happened to be at your country estate, breakfast was likely set out on a sideboard, where it was available for hours (via "Daily Life in Victorian England"). That was especially useful if you had a large household or were entertaining a bunch of your rich friends, who might amble their way downstairs and chow down in a leisurely fashion. Likewise, the food itself was a simple though usually high-quality array of meats, cheeses, and carbs. Tea was, of course, a given, as was the leisurely pace. After all, it's not as if all of you were obliged to hurry into the factory or at one of those newly emerging desk jobs.

Breakfast at a country estate had its own food and rules

While taking some time for yourself on your expansive country estate, you would surely have been mindful of breakfast. What you ate, along with when you ate and with whom, could be a matter of distinction that could make it break a reputation. While "Daily Life in Victorian England" does note that breakfast was often set out and made available on a rolling basis, the timing of when you came down for vittles could be noted. As "The English Breakfast" notes, many diners could get rather fixated on eating in a properly masculine manner. That could mean getting up early and wandering about the grounds, working up an appetite so you could consume hearty, nourishing foods in the company of other manly men. Women could pass, perhaps claiming to have delicate, "feminine" appetites. However, any man who took breakfast in his own room was potentially considered effeminate.

Breakfast at one's country home was often a lavish spread, despite aristocratic claims to their version of simplicity. According to "The English Breakfast," this often included plenty of meat, from cold cuts to game to fish, and of course, freshly cooked bacon and sausage. Vegetables were apparently a bit rarer, but there were plenty of eggs and pastries, with a bit of fresh fruit served towards the end. Of course, coffee and tea were both available for everyone's caffeinated benefit.

Tea time was a ladies' teetotaling affair

When friends come to call, aristocrats often set out the snacks. In earlier eras, that often took the form of cakes and wine, according to "Daily Life in Victorian England." As time went on, however, it became less desirable for women to drink, and so tea began to replace tipple. By the 1840s, the practice of afternoon tea was firmly ensconced in Britain.

By then, tea was no less than a way of life for just about everyone in the British Isles. As Historic UK notes, it had been introduced centuries earlier in the 1660s by King Charles II and his Portuguese-born wife, Catherine de Braganza. Supposedly, it was Anna Maria Russell, Duchess of Bedford, who started the afternoon tea craze in the 1840s. Given that Anna and her high-class friends often dined late in the evening, as was fashionable for the upper class at the time, she got peckish around four in the afternoon. She asked for a tray of tea, along with some pastries and a simple bread and butter concoction, and thus, afternoon tea was born (via British Museum).

As with so many human things, it got more complicated over time. What had begun as a simple snack tray eventually bloomed into a social event, complete with an outfit change for upper-class women. The fare got more complicated, too, growing to encompass sandwiches with thin slices of cucumber, an array of pastries, clotted cream for your British-style scones, and imported tea.

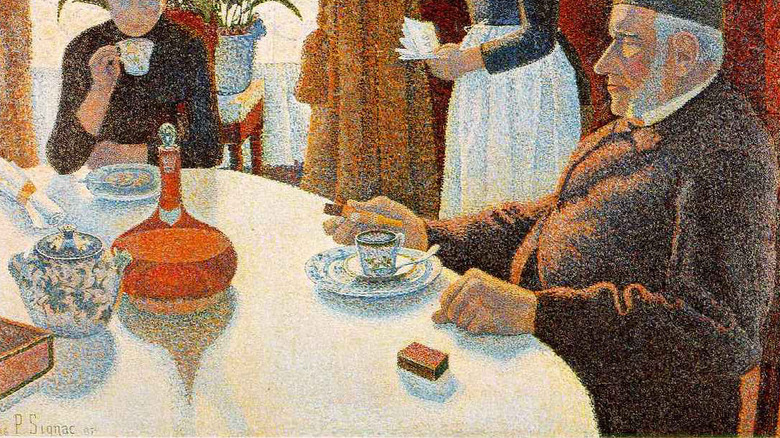

You couldn't have tea without a whole lot of food and accessories

While the hoi polloi might snag a simple cuppa, upper-class Victorians made tea a whole thing. How else could you show off your wealth if not by nibbling on dainty little cakes and having an opinion about when, exactly, you're supposed to add cream to your cup? That's a topic of debate that may have marked out class divides. As per the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum and tea expert Bruce Richardson, the old tale is that aristocrats poured the milk in first to keep their fine china cups from cracking under the thermal shock of boiling hot tea. Only, that's not exactly how tea is served up, and pouring the milk in first may make it harder to judge the strength of one's brew. Richardson maintains that formal occasions dictate pouring the milk in after the tea.

Regardless of where you fall in the milk and tea debate, it's clear that the ritual of afternoon tea simply wasn't complete without food accessories. These included fancy porcelain tea sets and other accouterments that were mostly intended to show off the fact that people could buy such things. According to the British Museum, this included an array of porcelain goods, silver tea trays, and even custom tea blends. The array of little sandwiches and cakes was also far more likely to be seen on a high-class table than in a more informal middle or lower-class setup.

A Victorian aristocrat's lunch was a little more formal than breakfast

Luncheon often had more structure than the combatively freewheeling breakfast, but it wasn't subject to the plethora of rules that governed an aristocratic dinner, either. It often consisted of relatively simple fare that was uncooked or only lightly cooked, according to "How to Be a Victorian." This could include vegetables that were prepared in a fairly simple manner, such as asparagus or peas dressed with a bit of butter. Meat could be served hot or cold and might also be complemented by an array of pickled items, cheeses, and, of course, a dash of fortified wine like sherry or claret. Shooting parties, popular at country homes, might naturally spell the inclusion of game meats like pheasant or grouse as well (via "The English Breakfast").

Though eating from a buffet-style setup, an aristocratic lunch could still include silver tableware and was set up by servants. As such, it could seem rarefied to modern spectators, but this really was a less formal affair than dinner. As "How to Be a Victorian" notes, an invite to lunch wasn't such a big deal, at least not compared to dinner with its dress requirements, seating arrangements, and unspoken social rules. Thus, an ambitious or lucky person might find an opportunity to mix with the snobbish types at luncheon, where they were less likely to be shut out altogether.

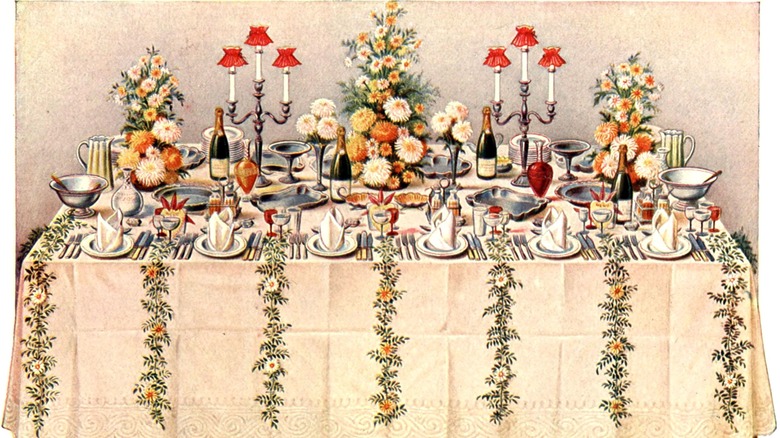

Multi-course dinners were packed with food

While there were surely plenty of informal dinners for Victorian aristocrats on the go (or at least those who were in a hurry or who weren't inclined to impress their super-rich friends all the time), this time and social class were notorious for elaborate, elegant dinner parties. According to "Fannie's Last Supper," the highly structured Victorian dinner party has its roots in a long history of such get-togethers, all apparently put on with the simultaneous purpose of making social connections and showing off to one another.

But you weren't expected to eat everything on the menu at a fancy dinner, especially given that pigging out may have been frowned upon. As "Daily Life in Victorian England" notes, guests would likely have seen a preplanned menu and were able to politely decline courses as they saw fit. One sample menu presented by household management celebrity Isabella Beeton called for three courses absolutely loaded with goodies, from filet of beef to macaroni and cheese to veal. Alas, there was also the presence of boiled meats, including boiled ham and salmon, as well as an entire boiled leg of lamb. At least there was a dedicated wine for each course, which may have lessened the sting of missing out on properly roasted meat.

You had better learn to like oysters

Today, oysters might be something of a divisive dish. Some people love the briny, mineral-rich taste of these bivalves, raving about how it's no less than a delectable taste of the sea. Of course, many say you simply must consume them raw. Then again, there are plenty of other less complimentary folks who say that oysters both look and taste like something an allergy sufferer has left behind in a handkerchief.

If you were a Victorian, however, it would be almost impossible to get away from oysters, so you might as well learn to like them. According to "Fannie's Last Supper," the Victorians were simply mad for the little things, which were easy to find and harvest. Well before Queen Victoria came along, oyster beds in the Americas were already seriously overfished, to the point where unscrupulous oystermen would dump outside oysters into more prestigious oyster beds so that they could charge higher prices for them in the coming harvest season.

All of this meant that just about everyone in Victorian society, regardless of social class, could access oysters. While the plebes were buying theirs from the early ancestors of food trucks or oyster houses, the higher classes were still serving them at their fancy dinner parties. It would have been odd indeed if there were a menu without oysters making an appearance at the beginning, to the point where, eventually, there were even dedicated oyster-serving dishes (via "Fannie's Last Supper").

Jellies were a way to show off

At the nicest class of Victorian-era dinner parties, hosts would show off an array of oftentimes elaborate jellies. According to "Fannie's Last Supper," these would have often been made with boiled calves' feet before the debut of powdered gelatin in the food world. These desserts could get pretty elaborate, with a plethora of ingredients that could include creams, fruits, and more. If you had an especially creative cook on staff — perhaps one of those fancy French chefs if you were really bringing in almost obscene amounts of cash — then the jellies could become miniature artworks. Some especially intricate ones involved complex molds and multiple layers that had to be carefully assembled in the kitchen.

Today, Victorian jelly molds are themselves works of art that speak to the intricacy of these desserts. Food historian Ivan Day notes that some could get downright architectural. Tables could be laden with jiggling ziggurats of fruit-laden jellies. Or perhaps, if pyramids of processed calf feet and berries weren't your thing, you might at least wonder at jellies that used multi-part molds to produce a result with a clear gelatin exterior filled with creams and fruits, sometimes in elaborate spirals that took considerable skill to pull off.

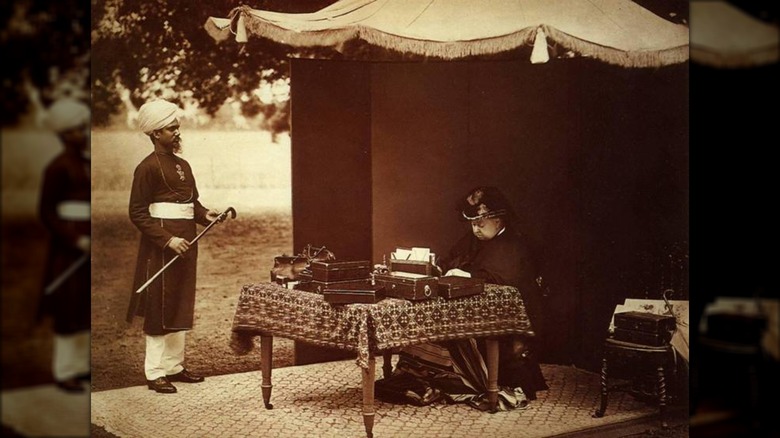

Some aristocrats chowed down on curry

Casual foodies today might happily nosh on a curry, thinking they're consuming an authentic Indian meal straight from the subcontinent. However, the truth is that, while the flavors and ingredients certainly have a foot in the diverse foodways of India, the meal's origins are settled pretty firmly in a Victorian kitchen.

The popularity of curry in Britain has much to do with the ultimate aristocrat: Queen Victoria. According to English Heritage, Indian-inspired meals were already gaining interest in Britain due in part to the British Empire's centuries-long hold on India. The Queen gave the trend a serious boost in the 1880s when her attachment to servant Abdul Karim and other Indian staff led to Indian food requests sent down to the royal kitchens. The English curries weren't quite like the authentic meals prepared back in Karim's homeland — in fact, with seriously diluted spice mixes, they were but an echo of the spicy, vibrant meals of India. Still, curry proved popular amongst the British, even if it was seriously adulterated.

For many years, curry was mostly served at aristocratic tables, thanks to both the example of the Queen and the exclusivity of the ingredients (it's not as if a factory worker could easily stroll into the corner shop and snag some garam masala, after all). It was only after World War II that more people began to rotate to Britain from places including India that curry began to be served to people of all classes.

Ices were a popular Victorian treat

For those of us with modern refrigeration, the availability of frozen treats like ice cream and sorbet is all but a given. But even aristocrats during the Victorian period would have had far less access to ices, the category of sweets that included ice cream, though with some rather surprising flavors. Certainly, that was the case in the earlier decades of Queen Victoria's reign, when reliable refrigeration technology wasn't everywhere.

Admittedly, ices did become more democratic as the Victorian era moved forward and refrigeration technology was made more accessible. Yet aristocrats would have had an easier time getting ices onto the dinner table, as English Heritage notes that country estates had dedicated ice houses to store the necessary ingredients (not to mention dedicated kitchens to make the dish). Some of the flavors would have seemed sweetly familiar to modern foodies, while others, like cucumber ice cream, are quite a bit more of the time.

Ultimately, celebrity chef and writer Agnes Marshall opened up the world of fancy frozen desserts to the middle classes with cookbooks and her National Training School of Cookery (via History). Marshall's recipes, which included both cucumber and duck-flavored ice creams, bridged the narrowing gap between classes, at least in terms of food. Dinner parties that required a team laboring away in an unseen kitchen for the benefit of the aristos in the dining room began to share far more with the table captained by an adventurous middle-class housewife and her cook.