Every Time Russia And The United States Were Friends, Explained

In 2017, President Donald Trump stunned America when he argued (via CNBC) for pursuing friendly relations with Russia. For Cold War children, this was shocking. Russia and the United States had always been enemies. But Trump's idea was not quite as radical as it might have seemed. In fact, it was grounded in American diplomatic tradition, while opposition was in part based on a conflation of terms. The United States was a rival of the USSR — not necessarily Russia. On the other hand, Russia proper was the United States' greatest friend from the earliest days of the Republic until the early 20th century.

The story of Russo-American relations is a virtually unknown chapter of American history, completely absent from standard textbooks and school curriculums. However, between 1776 and approximately 1904, the United States and Russia supported each other in the international arena including during the War of 1812, the Crimean War, the American Civil War, and in peacetime negotiations. Russian dignitaries were welcomed with pomp and ceremony fit for friends rather than allies, and the two nations exchanged luminaries, technology, and ideas as early as the colonial period. Here is the story of America's longest and perhaps most important international friendship and its abrupt end in the early 20th century.

Before the Revolution

Russo-American relations began before the 1775 American Revolution and were mostly the product of a single man's correspondence with Russian luminaries. The man in question was Benjamin Franklin, who, according to the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, made a name for himself among Russia's cultural elite in 1752. Franklin experimented with electricity to the fascination of Russian scientists such as polymath Mikhail Lomonosov. The two became acquainted through correspondence, making Franklin a hero in educated Russian circles. Soon, Franklin expanded his Russian circle to include Lomonosov's contacts, leading to an exchange that would see two people — an American and a Russian — elected to the other's scholarly society.

Franklin's most famous correspondent was the brilliant Princess Yekaterina Dashkova. At the tender age of 17, she had helped place Catherine the Great on the throne and become president of the Russian Academy of Sciences by 1780. She inspired respect from Europe's intellectuals and leaders, including Frederick the Great of Prussia and Marie-Antoinette of France, placing her on par with other female luminaries such as Venetian Elena Cornaro Piscopia. Dashkova reciprocally recognized Franklin's brilliance, and the two met on a few occasions during Franklin's sojourn in Paris.

In mutual recognition, Dashkova nominated Franklin to the Russian Academy of Sciences, and he became its first American member in 1789. Dashkova in turn became the American Philosophical Society's second Russian and first female member in 1791. These close cultural relations foreshadowed the Russo-American friendship that would develop in the 19th century.

August 13, 1776

According to the Journal of American History, the Declaration of Independence reached Russia on August 13, 1776, through London-based diplomat Vassili Lizakevich. His report wisely omitted any mention of the declaration's anti-monarchist sentiments, highlighting instead the American declaration of war against Russia's British rival and noting that the newly-minted United States could possibly serve as a future Russian ally.

The American Revolution was a hit in Russia. Lizakevich and other Russian elites emphasized the United States' right to break away from Britain following George III's failure to redress the colonists' grievances against the British crown. The Founding Fathers inspired respect for their stand against Britain in defense of their rights and privileges (which ironically were nonexistent in Russia). Russian poet and liberal thinker Aleksandr Radishchev even glorified the Revolution in his poem "Volnost'" (Liberty). Russian writer Pavel Svinin later called the United States a "people of profound knowledge and great virtues."

America's Russian admirers all ran in Russian courtly circles, and some were employed in the imperial government. So unsurprisingly, their glowing reports came to Catherine's attention. She decided to favor the nascent United States — even if out of self-interest rather than respect for the values enshrined in the Declaration of Independence.

The American Revolution

When armed conflict broke out in 1775, Great Britain, per the Journal of the American Revolution, first approached Russia for 20,000 soldiers to crush the revolt. Russia agreed, but only if Britain ceded the Spanish Mediterranean island of Menorca, which would have expanded Russia's Mediterranean influence. George III refused, so Catherine broke off the deal.

As the war dragged on, Russia grew more sympathetic to the American cause, particularly once Russian shipping ran into the British blockade of the East Coast. Russia declared the League of Armed Neutrality, whose signatories agreed to attack British warships obstructing neutral shipping with the United States. The czarina hoped that the risk of a wider conflict would bring Britain to the negotiating table. However, Charles Cornwallis' 1781 surrender at Yorktown and the subsequent Treaty of Paris ended the need for Russian involvement.

While American scholars explain Catherine's actions purely as arising from self-interest, the Russian International Affairs Council tells a different story. It argues that George III offered Russia the island of Menorca, but Catherine refused out of sympathy for the United States, which was founded on the same Enlightenment beliefs she claimed to admire. Catherine and her subjects corresponded with Enlightenment-minded thinkers (she and Benjamin Franklin shared mutual friends, after all, per the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society), so it is possible that she sympathized with the idea of the American cause — as long as it stayed in America. But her later statements suggest that she eventually tired of America by the 1780s.

The Barbary Wars

After the Revolution, Russo-American relations abruptly ended. According to Monticello, Catherine concluded that the American experiment was filled with "unbecoming impertinence" and refused to recognize the new nation. The two went their separate ways, but the United States soon faced trouble with the Barbary States of North Africa, who plundered American ships and enslaved crews. So according to a letter from James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, the United States appealed to Russia's Alexander I for help. Madison also noted that the czar had an unusual interest in the future of the American Republic, noting that this sympathy came from the czar's education under liberally-minded tutors such as Frederique-Cesar de la Harpe (via National Archives).

The appeal for help was referenced in Consul Levett Harris' communique, which appealed to Russia to pressure the Barbary States' de jure sovereign — the Ottoman Empire (via U.S. State Department) — into reining in their wayward North African subjects and releasing a captured American frigate. According to Jefferson's 1804 letter to Alexander, Russian pressure worked. The sailors were released and the two men struck up a brief correspondence and even exchanged presents. Jefferson gave the czar a series of books on the American government,while Alexander gave the United States a bust of himself and a book on Russian customs. This relationship was not purely political, though, and in a letter to William Duane, Jefferson wrote that "a more virtuous man [than Czar Alexander I] ... does not exist."

The War of 1812

By 1812, Russo-American relations had dramatically improved, although the two — perhaps in part due to George Washington's warning against "permanent alliances" — were not officially allies. But the young republic soon found itself at war again, this time against its former British colonial master.

The War of 1812 went badly for the United States. As Britannica notes, the British burned D.C., captured Detroit, threw the Americans out of Canada, and blockaded the East Coast. Fortunately for the Americans, Czar Alexander I came to the rescue. According to Political Science Quarterly, Russia had every interest in ending the war. Although Britain was a Russian ally against Napoleon's France, Russia considered the United States an important trading partner and friend. Furthermore, Alexander did not want British forces tied down in America should they be needed in Europe against Napoleon. So he offered to broker peace. President James Madison accepted, and an American delegation set off for St. Petersburg to negotiate.

The British initially refused to end the war, but eventually caved in 1814. Under Russian mediation, the two sides signed the Treaty of Ghent, which restored the pre-1812 status quo. In a letter to Madame de Staël Holstein, Thomas Jefferson praised the czar, writing that the czar's "immortal character" and impartiality would produce a just peace that would secure freedom at sea for American sailors — a major cause for the War of 1812. Alexander did not disappoint, and America lived to fight again.

The Convention of 1824

Although Russia and the United States were increasingly on friendly terms, the issuance of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 threatened to undo that progress. According to the journal Diplomatic History, the Monroe Doctrine was an American policy statement officially opposing European expansion in North America — including Russian colonization of Alaska and the Pacific Northwest.

Russian colonization of Alaska had gradually moved south into the area known as Oregon Country while American colonists gradually moved north. Unsurprisingly, disputes arose over navigation and fishing rights, trade with the natives, and territorial boundaries. The Convention of 1824 rectified these problems peacefully.

The Convention of 1824 set the boundary between American and Russian territory at 54º40' N latitude. The American traders and fishermen were forbidden from operating inside Russian settlements without local permission and vice-versa. Both sides, however, were permitted to freely trade with Native Americans, provided that neither side sold firearms, gunpowder, or any sort of "spirituous liquors" that could possibly be used against the other side's colonists. The treaty proved a boon to the United States, but per the Pacific Historical Review, ended up undercutting the Russian-American company by allowing American mercantile competitors into Russian Alaska. This would lead to the decline of Russian influence in America and the eventual sale of Alaska to the United States.

The 1840s

During the industrial revolution, Russia began experimenting with railroads beginning in 1837. According to the University of Missouri, Czar Nicholas I hired Austrian engineer Franz Anton Ritter von Gerstner to build a line — the country's first — between St. Petersburg and the imperial residence of Zarskoe Selo. However, the project ran well over budget, so the czar sent two representatives to the United States to study more advanced American railroads and hire an American consultant.

Russian engineers Pavel Melnikov and Joseph Kraft visited the United States, filing a report (via RLHS) on the superiority of American railroads, whose technology they hoped to bring to Russia. Per the University of Chicago, they also discovered George Washington Whistler, an American civil engineer and West Point graduate who had the requisite experience the two Russian officials sought.

Nicholas decided to hire Whistler, who arrived in St. Petersburg in 1842, to build a 400-mile long railroad between the Russian imperial capital and the old capital of Moscow. Whistler's imported American machinery cut the building times dramatically, completing in one hour what 16 Russian workers could do in two days. Having proven himself, Nicholas received him personally at the Russian court and promoted him to the national Technical Commission. Unfortunately for Whistler, war in Central Europe drew Russian laborers into military service, slowing construction progress, and the engineer died in 1849 of heart disease before the project was complete. But it marked a willingness by Americans to share their expertise with Russia, who would soon receive indirect American backing in the Crimean War.

The Crimean War

According to Britannica, a Franco-Russian dispute over custodianship of the Holy Places in Ottoman Jerusalem and the protection of Ottoman Christians ignited the Crimean War in 1853. The conflict pitted Russia against Britain, France, and the Ottomans. Russia, however, could count on an unexpected friend in the war — the United States.

Per the Russian Review, the United States and Russia were friends by 1853 and were deemed likely to enter into a formal alliance, in part because Great Britain and France wanted to see both countries dismembered. However, the United States eschewed foreign alliances on principle and refused to intervene directly in the conflict. Instead, per the American Historical Review, the United States built ships for the Russian navy, prevented Britain from recruiting American citizens, and supplied Russia under the American flag as a neutral party. SInce America was neutral and becoming an increasingly-powerful country on the international stage, the British did not search the ships, handing Russia a commercial lifeline. Finally, a handful of American surgeons served on the front lines of the war, many of whom died of disease.

The cooperation in the Crimean War proved to be mutually beneficial, even though Russia lost. The United States sent Captain (later general) George McClellan to visit Russia in 1855. McClellan had nothing but high praise for Russia, and he recommended replicating Russian cavalry tactics on the frontiers against Native Americans. Russia would repay its debt to the United States in kind during the Civil War in 1863.

The abolition of serfdom and slavery

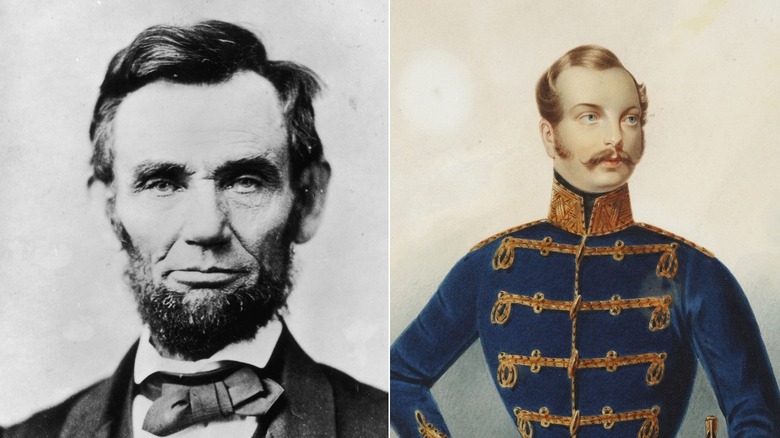

The early 1860s catapulted Abraham Lincoln and Alexander II to the world stage. Their countries could not have been more different. Per the University of Hawaii, the United States was a constitutional republic while Russia was an absolute monarchy. Yet, the two men found common ground not only in their anti-British interests, but also on the twin questions of serfdom and slavery. According to History Today, a large portion of the Russian population lived in serfdom. Although not slaves, serfs were bound to the land they were born on and could not leave without permission from the lord. Noting that this system was economically inefficient, the czar abolished it in 1861.

The czar's action drew praise from American abolitionists, who hoped to end American chattel slavery in what became the Confederacy. Notably, the abolitionists pointed out that even autocrats like Alexander and his father Nicholas I abhorred slavery, which therefore had no place in a free America. In 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and suddenly, both men became paragons and champions of human liberty –– even though they were ultimately issued under different circumstances. As the New York Times wrote in 2011, a special exhibition in Russia on the emancipation of the serfs included the pen Lincoln used to sign the Emancipation Proclamation — a sign that while this link has been forgotten in the United States, Russia still remembers, especially since without Russian backing, the Emancipation Proclamation may never have seen the light of day.

The American Civil War

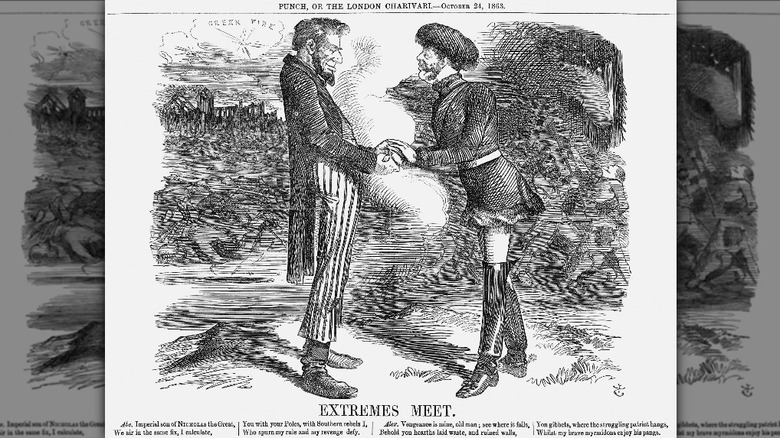

Russo-American friendship reached its apex when the very existence of the United States was in question. According to the University of Hawaii, most of Europe — including American commercial and military rival Great Britain — supported the Confederacy in hopes of seeing the U.S. dismembered and eliminated. Russia, however, was the sole European power to back Abraham Lincoln, declaring the preservation of American unity as a key Russian national interest.

The success of the Confederacy depended on European recognition and possible military intervention. Per Russia Beyond, Britain and France were seriously considering intervention from 1862 to '63. In fact, according to History, the former had readied soldiers to invade through Canada. But Russia soon scuppered any Confederate hopes for British intervention. In 1863, Alexander II dispatched a fleet of Russian warships to New York and another to San Francisco. The statement was clear. If Britain or France intervened, they would face Russia and America together.

Historians (via Mississippi Valley Historical Review) believe that Russia sent its fleet to New York not out of goodwill, but to have a base against Britain and France if war broke out over Poland. However, the Russian navy could obtain this base of operations while still showing goodwill towards America. The czar's motivations were not mutually exclusive. The close relations in the previous decades and the reception of Russian imperial dignitaries after the war suggest that Alexander did intend to back the United States against Britain, especially since Britain had planned the destruction of both Russia and the United States.

The Alaska Purchase (aka Seward's folly)

During the 1850s, the Russian American Company had fallen on hard times. According to the Western Historical Quarterly, despite early successes, the cost of maintaining its colonies in Alaska was proving to be unsustainable even as American prospectors and merchants descended upon the territory as competitors. Russia, however, faced a problem. According to the State Department, Britain — the main Russo-American rival — also wanted Alaska (via Library of Congress). So Russia hit upon a solution — sell the territory to the United States to keep Alaska out of British hands. In 1859, Russia made the United States an offer, but the deal was postponed following the outbreak of the American Civil War.

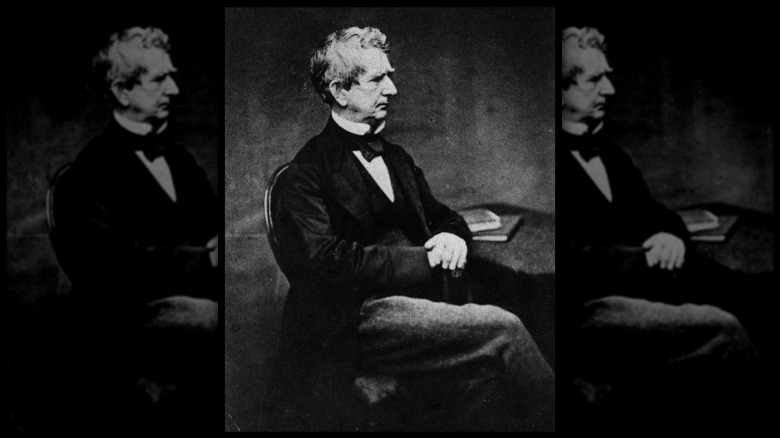

In 1867, Secretary of State William Seward offered to take Alaska off Russia's hands for $7.2 million. The treaty, which was signed on March 30, officially completed the transfer of Alaska to the United States. Russian citizens, including those of mixed Russian-Alaska Native descent, were given the option of American citizenship, while the Russian Orthodox Church was granted freedom of worship and the integrity of its properties.

Despite the success of the deal, the American public was not impressed. According to the Library of Congress, Alaska was considered a frozen wasteland, earning names from "Seward's Ice Box" to President Andrew Johnson's less-famous but hilarious "polar bear garden." The public called the purchase "Seward's folly." However, the secretary was proved correct once gold was discovered in Alaska in 1890. Suddenly, the territory didn't seem so useless anymore.

The Gilded Age

During the Gilded Age, Russo-American relations reached their zenith. Among the famous literati to visit Russia was Mark Twain, who according to Russia Beyond, visited in 1867. Although apprehensive thanks to stories of Russian autocracy and Siberia, Twain enjoyed the Black Sea towns of Odessa, Sevastopol, and Yalta, where Czar Alexander II received him. Twain thanked Russia for its Civil War support and effusively praised Alexander for his emancipation of the serfs and pro-American politics. His only regret? Not stealing the czar's coat as a souvenir.

In the opposite direction, many Russians visited the United States, most famously the Grand Duke Alexei in 1871. At this time, the Russian imperial family held celebrity status in the United States, and the handsome duke was no exception. According to the Ephemera Society, Alexei received a true friend's welcome. Every stop along the train line was marked by balls, toasts, and crowds of female admirers. Rail lines were cleared to ensure the duke's train could pass unhindered.

The tour took Alexei to gun factories, steel mills, agricultural facilities, the Harvard University Library, and even West Point, which gave him the honor of reviewing the corps of cadets. In Chicago, recently gutted by the Great Fire, Alexei donated $5,000 for citizens' relief. He ended his visit with a buffalo hunt — his favorite part of a trip that has largely vanished from American memory.

The Famine of 1891-'93

By the late 19th century, Russo-American relations began to decline. The American press, per the Russian Review, increasingly reported on pogroms against Jews (many of whom immigrated to America), casting Russia in an increasingly negative light. But for many Americans, the Famine of 1891-'93 solidified a negative view of the czarist state, despite a more philanthropic start.

The Russian Review notes that when famine struck Russia, Americans — particularly in the Midwest — rallied to contribute foodstuffs, blankets, and other humanitarian supplies for Russia's starving peasantry. Unfortunately, Russian mismanagement hamstrung the relief effort, to the chagrin of those who had donated.

American observers in Russia complained that once the aid reached Russia, unscrupulous government officials hoarded the aid to resell at higher prices or simply pocketed relief money. Meanwhile, American accused the Russian government of stripping harvests from the worst-affected provinces for export abroad, suggesting that American relief had never been needed in the first place. The American press and observers laid the blame upon Czar Alexander III. Once the United States and anti-Russian financier Jacob Schiff (via the Journal of International Relations) bankrolled Japan against Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, America's oldest friendship gradually died, never to be resurrected.

World War II

The United States and Russia never again became friends or allies after 1917. Russia ceased to exist as an independent state after the Bolshevik Revolution replaced it with the Soviet Union. As the State Department notes, the United States and USSR (not Russia) were allies during World War II, when the Americans supplied the Soviets under the Lend-Lease Act and opened a second front against Germany to relieve Soviet armies with the D-Day landings. The attack which saw Allied forces drive the Germans out of France all the way to the German border itself and was widely credited with ending the war in Europe (via History). The combination of the Soviet invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria and American atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki then helped end the Pacific War.

The Soviet-American alliance of World War II, however, was just that — an alliance of convenience — not the Russo-American friendship of the 19th century. Once the war was over, the two superpowers became Cold War rivals until the USSR collapsed in 1991. Since the restoration of Russia's independence, relations with the United States have gradually worsened, despite Vladimir Putin's suggestion (via the Guardian) for de facto resurrecting the alliance by joining NATO in 2000. Today, the story of America's longest friendship remains conspicuously absent from the history books.