How The Murder Of David Kammerer Influenced The Beat Generation

When thinking of "the Beats," or "the Beat Generation," folks might envision a troupe of proto-hippie, pleasure-seeking vagabonds snapping their fingers at poetry recitals while making road trips along the old Route 66 cutting through the center of the United States. Some might recall certain Beat figures, like Jack Kerouac (writer of "On the Road," 1957) or Allen Ginsberg (writer of "Howl," 1956). Others might make the very real connection between the Beats in the 1940s and '50s, and the counterculture of the 1960s a generation later.

There are glimmers of truth in all these descriptions, but beneath it all, there were very real people snared by a very dense web of relationships, love, sex, betrayal, frenzy, and straight-up murder. Kerouac and Ginsberg were the public faces of the Beats when the movement came to national light with the publication of "On the Road." But even their clumped-together "Beat" identity split into Janus-faced opposites: crushing mid-life alcoholism for Kerouac, and Buddhist raconteur for Ginsberg. There was never any strict consensus on what it meant to be "Beat," although in an interview with William Buckley in 1968 a very drunk Kerouac said that the Beats were about "tenderness," as Lit Hub discusses. This makes sense given that "beat" was 1950s slang for down-and-out people with passionate convictions, as defined by Your Dictionary.

And yet, none of the Beat's work might have happened without a single, tragic event: the murder of David Kammerer by friend-of-the-Beats Lucien Carr, the object of Kammerer's amorous preoccupations.

Down and out after World War II

The Beat Generation, its art, ideology, and subsequent influence, owe itself to the post-World War II shock and ennui that gripped the world at large in the 1940s and '50s. At the same time as Baby Boomers were being reared with ultra-conservative, traditional notions of family structures, love, work, etc., the Beats rose as a young, countercultural juggernaut.

A generation prior, the dehumanizing, mechanized horrors of World War I — machine guns, gas warfare, and human fodder by the millions — had yielded Modernist literature: books with the pared-down realism of folks like Ernest Hemingway. This kind of work and its language tried to portray life as merely life, full of tooth-brushing, interior character conflicts, and the kind of discarded romanticism engendered by the war (as History outlines).

The Beats, similarly, were the by-product of World War II, and turned to a "live life my way and honestly" outlook, and spontaneous, ultra-creative literary work. As The Beat Museum describes, the Beats didn't fight the emptiness of life or question what might be done tomorrow — they turned their attention to squeezing the most out of the here and now. "On the Road," as the drug-fueled poet and Beat mentor William S. Burroughs describes, "sold a trillion Levis and a million espresso machines, and also sent countless kids on the road. The alienation, the restlessness, the dissatisfaction were already there waiting" (quoted from Goodreads). Such restlessness, drive, and passion, though, could easily turn destructive.

A love quadrangle between poets

People who've read "On the Road" know that Kerouac's book is littered with itinerants, transients, vagrants, and cross-country drifters. It's a portrait of the lives of the dispossessed, and Kerouac wrote it in three weeks. It's also semi-autobiographical. Each of the book's characters — from the odd to the wacky, the misanthrope to the misunderstood — is modeled after a real person. Dean Moriarty, the young man who fascinates Keroac's stand-in protagonist Sal Paradise, was Neal Cassady, a lover of Allen Ginsberg's, as Beatdom describes. Damion was Lucien Carr, "Lou the glue" who kept the Beats together, as Ginsberg put it.

One person who did not make it into "On the Road" was David Kammerer. Kammerer, as The Paris Review discusses, was a professor of literature and physical education at Washington University. He started off as Carr's teacher and grew infatuated with the young man. When Carr moved to the University of Chicago, Kammerer followed. When Carr then moved to Bowdoin College in Maine, Kammerer followed. When Carr finally moved to Columbia University in New York City, Kammerer followed. While it seems clear that Carr was more or less running away from Kammerer, William S. Burrough's biographer Ted Morgan stated that when the two men were seen in public, they "seemed to be the best of friends, drinking and horsing around."

And yet, Carr "had always rebuffed the older man" for his "improper advances." Meanwhile, Kerouac and Ginsberg both started competing for Carr's affections, per The Paris Review.

Murder by the Hudson

Some folks posit Lucien Carr, a young man of "delinquency, good looks, and intellectual charm" (per The Paris Review), as a tease who drew David Kammerer to madness. Others frame Kammerer as an over-age predator stalking a vulnerable youth. Both extremes are overly simplistic; like most things, reality rests somewhere in the middle. We'll never know precisely what went on between Carr and Kammerer on a moment-to-moment, private basis, or within the entire webwork of Beat relationships, nor is that our right. We do know that come August, 1944, things came to a disastrous and tragic head.

At the time, after following Carr from city to city, Kammerer had taken up work as a janitor in Greenwich Village just to be near the younger man. They would hang out, often at a favorite bar called West End Café on Manhattan's Upper West Side. All the nascent Beats and their associates congregated there, including Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs, where in the stew of alcohol and discussions of literature and art, Beat ideology took form. Carr himself was known for erratic behavior when he drank, including chewing glass shards and chucking plates.

On the night of Kammerer's murder, Carr and Kammerer left West End Café and ambled over to Riverside Park a couple of blocks away. Carr showed up sometime early the next morning at Kerouac's door. He'd stabbed Kammerer in the heart with a Boy Scout knife, repeatedly, and tried to hide the body in the Hudson River.

Marred by blood and madness

Carr didn't just stab Kammerer and put him in the Hudson. As The Paris Review explains, Carr worked frantically to gather as many rocks as possible and put them in Kammerer's pockets to weigh the dead man down in the river. When Carr went to Kerouac, the two of them buried Kammerer's glasses and dumped the murder weapon — the Boy Scout knife — in a storm drain. Then went to the Museum of Modern Art and spent the day drinking together while Kerouac talked Carr into turning himself in. Carr did, and he confessed to the murder even as Kammerer's body washed ashore downriver around 72nd Street.

This event scarred the psyche of the Beats — Carr's circle of friends — forever. Even beyond this one death and the deaths of World War II that spawned their entire generation, the Beats would become very familiar with personal tragedy. Years later after the death of David Kammerer jump-started the Beat's work in a literary sense, friend-of-the-Beats William S. Burroughs wound up accidentally shooting his wife in the head while attempting a party trick in 1951. As The New Yorker says, they had fled to Mexico City after Burroughs was arrested for forging prescriptions. There, while hopped up on Benzedrine and heroin, they played a game of William Tell with a gun with live rounds.

In the end, the opening line of Ginsberg's "Howl," published in 1956, says it all: "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness."

The whetstone of Beat writing

Allen Ginsberg, especially, took to processing his feelings about Kammerer's murder through writing, as The Paris Review discusses. In his journal he described dreams of wandering New York at night, haunted by Kammerer's death, and wrote, "The libertine circle is destroyed with the death of Kammerer." Faculty in the English Department of his creative writing class were shocked to see a passage titled "Death Scene" in Ginsberg's novella. In it, a murder victim declares, "Choose to present me with your pecker or your knife." The scene was overtly homoerotic, which shocked the faculty more than the violence, and reflected not only Ginsberg's attraction to Carr, but the complexities of the relationships between all men involved.

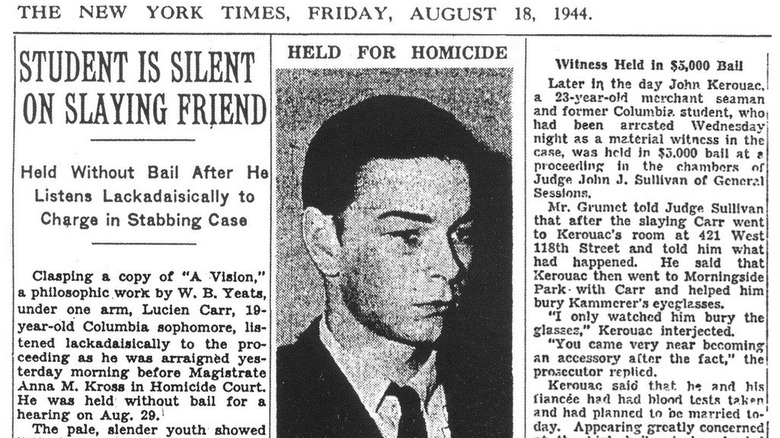

Carr himself received a mere 18-month sentence at Elmira Reformatory in upstate New York for Kammerer's murder. His defense, viewed by the legal system as highly sympathetic, amounted to him being the victim of an "unmanly homosexual who inflicted both physical and psychological harm on normal men." Kerouac mirrored this sentiment, writing that Carr had been, "subject to an attempt at degrading by an older man who was a pederast."

Kerouac, though, like many of the original Beats, was gay — or was at least bisexual, per Back 2 Stonewall. In the end, the Carr-Kammerer conflict became not only the whetstone for Beat writing, but embodied their struggle with the entanglement of sexuality, art, and societal norms regarding "masculinity" in the 1940s and '50s. After his release, Carr stayed away from the Beats for the rest of his life.