The Untold Truth Of David Attenborough

If the sight of a flock of birds migrating, a sweeping mountain range, or flowers coming into bloom has inspired narration with a British accent in your mind, then you've felt the influence of Sir David Attenborough. For almost 70 years, the broadcaster has presented the wonders of the natural world to audiences through the BBC. His ubiquitous presence in British television and his unbridled enthusiasm for everything he presents has earned him the label of national treasure in the United Kingdom, though when asked how he felt at being called such by BBC One, Attenborough was quick to self-deprecate (per GQ).

The middle child of his family, Attenborough wasn't the only high achiever of his generation. According to the Independent, his older brother Richard Attenborough was one of Britain's most accomplished actors and filmmakers and a member of the House of Lords. Younger brother John Attenborough was an auto executive. All three brothers served their country in World War II in different branches of the armed forces and remained close throughout their lives.

John passed away in 2012, and Richard in 2014. At 96, David continues his family's legacy of contribution to Britain and his own work on behalf of the natural world. He's gone all over the world, encountered everything from fireflies to mountain gorillas (see BBC Earth), and changed the face of British public television. Read on to learn more.

His family harbored refugees in World War II

David Attenborough was born on May 8, 1926, to Frederick and Mary Attenborough. He and his brothers grew up on the campus of the University of Leicester, where their father served as principal. According to the Independent, Frederick expected his boys to prove themselves if they wanted to pursue their passions. David was only allowed to take the qualifying exams for Cambridge after he won a scholarship, and older brother Richard faced a similar requirement before he could go into acting.

There was more to the Attenboroughs than strict academic standards, though. "My parents were radicals," Richard once wrote. In the 1930s, they worked to move Jewish refugees from Germany to safety in North America. But when war broke out, transportation became impossible. The Attenboroughs had two German girls on their hands, Irene and Helga, with nowhere for them to go. Despite the hardships it would put on the family, the elder Attenboroughs wanted to adopt the girls, but they left it to their sons to make the final decision. Richard was serving in the RAF, David in the Navy, and youngest brother John in the Army, but all three agreed to welcome Irene and Helga into the family. "We had no hesitation in taking them into our lives and loving and adoring and cherishing them," Richard told JFS School (via the Jewish Chronicle). "And I always remember Ma and Pa, who said 'That is the way to live.'"

He made his living off animals early

From a young age, the natural world fascinated David Attenborough. He lamented to the Daily Mail in 2014 that modern life has cut off so many children from having the direct experience with plants and animals he enjoyed, and that preoccupation with safety has stifled the spirit of adventure that led him out into the fields around Leicester — and beyond. At 13, he once spent three weeks on his bike, sleeping in hostels while he collected fossils. His parents had no idea where he'd gone. "I doubt many parents would let children do that now," he told the Mail.

Fossils weren't the only thing that young Attenborough hunted down. He sought out animals to observe and catch. Near his home, he could find birds, badgers, and newts. The latter brought Attenborough his first opportunity to earn a living on his natural world interests. According to the Leicester Mercury, the head of the zoology department of the University of Leicester needed specimens for her laboratory. Attenborough offered to supply her at threepence a newt. It helped his early enterprise that the adults running the lab had no idea that his newts came from a pond only five yards away from the building.

A lecture on beavers helped lead him to his career

A pivotal moment in David Attenborough's life was a lecture he attended in 1936. It was an occasion he and his older brother Richard were fond of relating in interviews later in life, though they disagreed on whether or not Richard actually came along (per the Independent). They both agreed that the subject of the talk was conservation, and the speaker was Grey Owl. Celebrated as a "Red Indian” from Canada in the '30s, his real name was Archibald Belaney, of Hastings. He deceived everyone from his young admirers, the Attenborough boys, to King George VI about his identity, practiced bigamny, and drank heavily (per the Guardian).

The persona he offered to the world was a lie, but Belaney's passion for conservation was genuine, and his lectures combined urgent warnings about the destruction of the natural world with eye-catching theatricality. Attending his talk changed both Attenboroughs forever. Richard wouldn't remember much of the lecture itself, but the showmanship of the presenter greatly impressed the fledgling actor, and in 1999, he directed the biopic "Grey Owl." David, on the other hand, was deeply moved by Belaney's words on behalf of the American beaver. When Richard consulted him about Belaney for his film, David called him "one of the first of his kind" of environmentalist. But he refused to loan out the autographed copy of Belaney's book the brothers had fought over back in 1936.

He started at the BBC with folk music

After serving in the Navy during World War II, according to his autobiography "Life on Air," David Attenborough initially found work — unhappily — in the editorial department of an educational publishing firm. An application to the BBC for a radio position was rejected, but Attenborough was later approached with an offer to join the broadcaster's training program for television, a medium then still in its infancy. By 1952, he was a full-time BBC employee.

Attenborough's association with the BBC, which continues to this day, has been defined in the public eye by his on-camera presentations of plant and animal life. But in the 1950s, his prospects for a broadcasting career seemed bleak. After one appearance before cameras, the same woman who offered Attenborough the spot in the training program made a note that his teeth were too big. Instead, he became a producer. And one of his earliest projects, according to "Life on Air," had nothing to do with wildlife. After hearing the American folk song collector Alan Lomax on the Third Programme, Attenborough developed the short-lived "Song Hunter," hosted by Lomax, to promote folk music from the British isles. He would later call its finale, which saw Lomax lead a procession through the studio without a mind to camera position, the most technically incompetent he'd attempted up to that point, but he considered it an important step forward in the British folk music revival.

He stated presenting because someone got sick

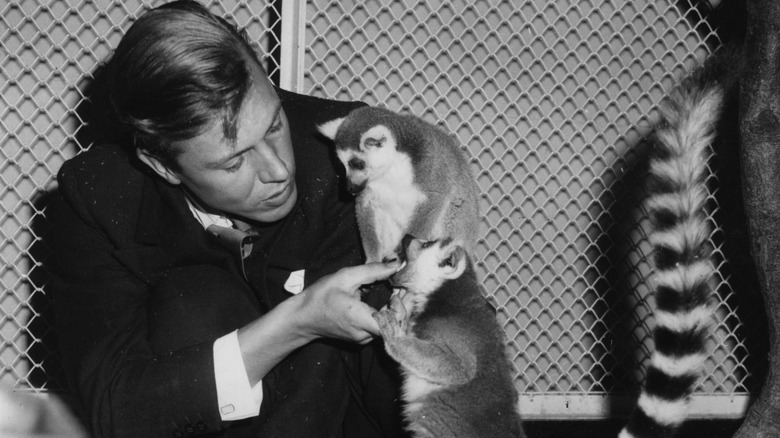

David Attenborough's long legacy as a producer and presenter of nature documentaries began in 1954, when he made the acquaintance of Jack Lester and Alfred Woods. They were zoologists for the London Zoo — Lester was head of the reptile house, according to the Spectator – and they were preparing an expedition to Sierra Leone to collect specimens. Would Attenborough like to come along and make a program of the trip? He agreed and joined the expedition with cameraman Charles Lagus to produce "Zoo Quest" (per the BBC).

Initially, Attenborough was only to be the producer of the series. Lester was intended to host, in segments filmed in the studio after the expedition's conclusion. But according to the Daily Mail, Lester contracted an unknown illness while in the tropics, eventually dying of the ailment in 1956. He was too sick to get before the cameras, so Attenborough reluctantly became the presenter of "Zoo Quest." Not only did he contextualize the footage shot in Sierra Leone, he brought a select number of animals captured during the expedition into the studio to offer audiences a closer look.

"Zoo Quest" continued for nine years with Attenborough as host (also per the BBC), with Lagus continuing on as cameraman. Attenborough recalled for the "Zoo Quest in Color" retrospective that the two of them worked largely unsupervised, choosing their subjects and arranging their own travel — something that wouldn't fly with the BBC of today.

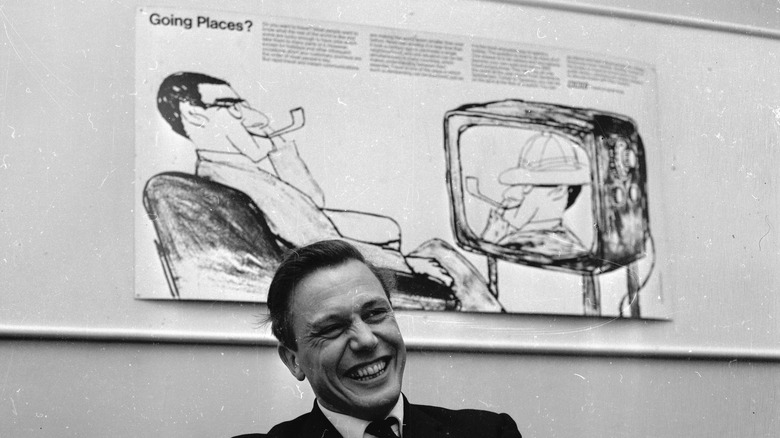

He was controller of BBC Two

As the 1950s came to an end, David Attenborough felt that the "Zoo Quest" series was beginning to feel dated (per the Guardian). A different series, filmed in Australia and focused on Aboriginal culture, inspired him to go back to school. He began a part-time course in anthropology with the London School of Economics (per Business Insider). Before he could complete his degree, however, in 1965, the BBC offered him the position of controller (chief creative officer) for BBC Two, the spin-off channel dedicated to programs "of depth and substance" compared to the more popular-minded BBC One (per the Telegraph).

Attenborough's appointment to controller was met with some skepticism. He was still relatively young in 1965, and he had already gained a reputation for his boyishly enthusiastic on-camera presence in his nature programs. Some observers felt that he wouldn't be up to the task of directing an entire channel's programming. Responding to his critics at the time, Attenborough pointed out that he was just as educated and enthusiastic about television production as he was natural history.

The programming that came out of Attenborough's tenure as controller silenced the critics. He was quick to seize the government's 1967 decision to make BBC Two the first color TV channel, putting such groundbreaking projects as Sir Kenneth Clark's 12-part "Civilization" into production to showcase both color and the best of world culture. He also gave the greenlight to everything from televised snooker to "Monty Python's Flying Circus."

He once turned down Terry Wogan

According to the Guardian, David Attenborough's tenure as controller of BBC Two wasn't just a success — it was a groundbreaking period in television. He championed the "sledgehammer" style of documentary, audience participation, new sports, and experimental programming. Attenborough himself couldn't resist sharing his pride in a 1965 interview. "I watch everything," he told the Daily Express. "Straight home from the office — switch to BBC Two — see all my babies."

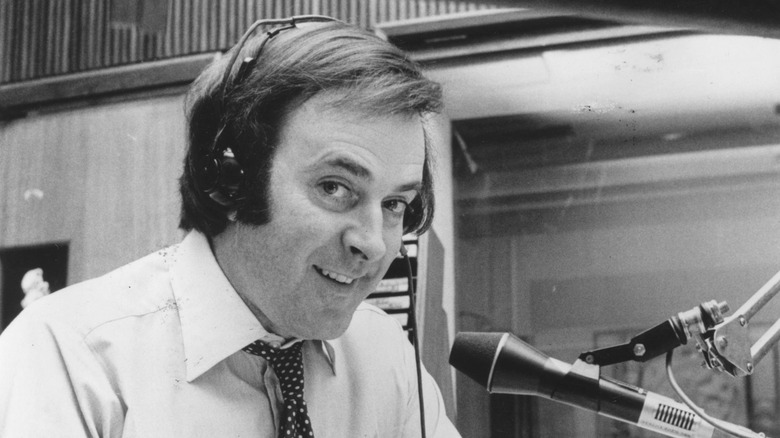

Not every decision Attenborough made as controller showed prescience for the future of television, however. According to Radio Times, Attenborough received a letter from a 27-year-old Irish broadcaster in 1965. Having enjoyed success in his own country on television and radio, the young man wanted to make inroads into Britain, and asked after any vacancies at BBC Two. Attenborough replied that there were no openings and that, should one appear, he would most likely seek someone from another part of the British isles, as one of his chief announcers was from Dublin already.

The young man Attenborough turned down was Terry Wogan, who went on to become one of Britain's most beloved broadcasters through his work with the BBC in radio and his TV chat show "Wogan." Reminded of the incident by Radio Times (via the Irish Independent), Attenborough pleaded ignorance. "Good Lord! He wrote asking me for work? I don't remember this at all."

He tried to protect the monarchy from a TV special

Scientists, secularists, and political lefties: three groups that don't immediately come to mind as candidates for monarchism. But David Attenborough has longstanding ties to the royal family. He and Queen Elizabeth II are only weeks apart in age (per Town and Country Magazine), and he first came into contact with the royals in 1958 when a young Prince Charles and Princess Anne took a tour of the Lime Grove television studio. Attenborough showed the royal youngsters a cockatoo from his latest "Zoo Quest" series.

In 1969, "Royal Family" premiered. A BBC documentary produced ahead of Charles' investiture as Prince of Wales, the film was made with the cooperation of the royals, particularly Prince Philip, according to the Independent, and was intended to help demonstrate the value of the monarchy to contemporary Britain. Attenborough played no role in making "Royal Family," but he did write its producer Richard Cawston — to warn him he was doing more harm than good. "The whole institution [of monarchy] depends on mystique and the tribal chief in his hut," he argued. "If any member of the tribe sees inside the hut then the whole system of tribal chiefdom is damaged and the tribe eventually disintegrates."

Perhaps Attenborough was on to something; 53 years out from "Royal Family," Britain's national identity is greatly troubled (per National Geographic). But the monarchy is still intact, and can still act as a unifier according to the Guardian.

He upset the Queen over Christmas

If David Attenborough, or Queen Elizabeth II, had misgivings over the impact the documentary "Royal Family" had on the monarchy after 1969 (per the Independent), once the media genie was out of the bottle, they both made their peace with it. The queen has continued to participate in film and television productions, and Attenborough has been a party to several of them. Most recently, they collaborated on "The Queen's Green Planet" for ITV in 2018. Attenborough has participated in climate-related ventures headed by the Duke of Cambridge, inspired Buckingham Palace to ban plastic straws, and received two knighthoods and the Order of Merit (per Town and Country Magazine).

Despite his warm relations with the royal family, Attenborough hasn't had entirely smooth sailing in working with them for the cameras. Between 1986 and 1991, he was responsible for producing the queen's Christmas address. He was personally requested for the job by Buckingham Palace, according to Attenborough's autobiography "Life on Air" (and apparently didn't have the option of turning it down). For the 1988 broadcast, Attenborough ran afoul of the present queen's dress sense. She had been told to dress colorfully, to be noticed in a crowd, but her choice of bright green on that occasion would have blended in with the green wallpaper of the room. Attenborough picked a "mushroom" dress instead. "Really," the queen told him, "there is no pleasing you people from the media."

He's faced critique from environmentalists

It's hard to picture a less likely target for environmentalists' ire than David Attenborough. The man has had a hand in well over a hundred documentaries as producer, writer, or host (per Science Alert), many of them concerned with the natural world. Yet, according to the Guardian, as the climate crisis has worsened and the extent of humanity's impact on every ecosystem has become more apparent, Attenborough's work has also been challenged for failing to adequately present the scale of damage to viewers — and for failing to address our collective culpability. Environmental activist George Monibot was particularly acid in his Guardian critique.

In response to these criticisms, Attenborough has pointed out the presence of conservationist themes in his work since at least the 1980s. And he's taken on a much more activist position in recent years (per another Guardian article). At the same time, he's repeatedly argued that too stringent and excessive warnings about planetary danger would alienate viewers and dilute the potency of the message. He also feels that, even with the urgency of climate change, there is more to nature than its vulnerability. "It would be irresponsible to ignore [climate change]," he's said, "but equally I believe we have a responsibility to make programs that look at all the rest of the aspects and not just this one."

He's been in hot water over population comments

Per the Guardian, David Attenborough has been slow to shift the focus of his nature documentaries toward a more cautionary and activist view. But that doesn't mean he hasn't had long-standing concerns about the environment or humanity's impact on it. One area that's particularly troubled him is the rate at which the human population is increasing. Population growth is so rapid in his estimation that he gave it as a reason not to be optimistic about the future in 2013 (also per the Guardian). He's a patron of the family planning charity Population Matters, one of his documentaries directly addressed the subject ("How Many People Can Live on the Earth?" in 2009), and he went as far as to call humanity "a plague on Earth" to the Telegraph.

This focus on population as a driver of environmental destruction has brought Attenborough some criticism. His views can be perceived by some as blaming poorer nations with high birth rates over excessive consumption in the developed world. And the extent to which population matters in the fight against climate change is debated. Sarah Kaplan in the Washington Post pushed back on the idea that curbing our numbers is necessary to reign in emissions, and New Statesman reported on direct criticism of Attenborough's population comments on factual grounds. Nolan McGregor of Jarrow Insights went as far as to call them "anti-scientific."