The History Of Sign Language Explained

As long as there have been humans, there have been humans who have not been able to hear. Sometimes deafness is experienced from birth, while other times, it occurs later in life, whether due to a sickness, an injury, or simply resulting from aging. How societies have viewed those who were deaf has changed drastically over time with more positive perceptions of deafness forming over the last few centuries. There have also been various ways in which those who are deaf have communicated, which inspired the formation of hundreds of different sign languages, dating back millennia.

In fact, according to Britannica, sign language among humans likely predates verbal speech. In terms of sign language specifically for those who are deaf, the journal Acta Oto-Laryngologica states that sign languages were recognized and understood as early as the fourth century B.C., although they wouldn't evolve and expand until much later. Nonetheless, sign languages are languages. National Geographic explains that they're merely visual in nature, but like any language, they contain their own rules, grammar, structure, and syntax. The World Federation of the Deaf states that sign languages deserve recognition, respect, and promotion as part of our diverse world.

Socrates was interested in sign language as communication

In "Cratylus," a dialogue written by Plato in the fifth century BC, the Ancient Greek philosopher wrote about language and linguistics; "Cratylus" has one of the first-ever references to what is now referred to as sign language. During a conversation between Socrates and two others, they discuss the relevance of names and words and the importance they have to us as human beings. Socrates then notes that if we didn't have "a voice or a tongue," then we would almost certainly "make signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body." He uses a horse as an example, saying one could use their gestures and even their whole body to communicate galloping.

According to Bruce N. Snider in "The Deaf Way," based on this dialogue, one can assume that both deaf people and the use of some form of sign language were present in Ancient Greek society. On the other hand, some scholars have also pointed out that it was assumed during antiquity that educating those who were deaf was not possible nor was it even attempted (per "The Deaf in Antiquity," via JSTOR). In fact, they were often flat-out denied educational opportunities, and Aristotle once even said that people who cannot hear cannot learn, as they would be "senseless and incapable of reason," something we now know is entirely untrue (via Ohio University).

Native Americans have used sign language for centuries

American Indian Sign Language (AISL), which is also sometimes referred to as "Hand Talk," is not one language, but includes as many as 41 different languages. It was first documented by Europeans in 1542, and while some have argued that it formed by necessity as a way to speak with colonizing Europeans, many experts agree it almost certainly predated European contact, per the "Oxford Handbooks in Linguistics."

One of the most well-known of these sign languages is Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), which as described by Britannica, was used among the deaf, but also during hunts as well as while trading with people of different spoken languages. From the perspective of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, signing in this way was one of the primary methods of communication among interpreters, because even though there were different singing languages (and even different dialects among those languages), it was a more effective way of communicating with people who used different spoken languages (per the National Park Service). According to Oklahoma's Museum of Natural History, it is considered an "endangered" language as there are so few people fluent in it today.

European views on deafness changed in the 16th century

In Europe, the 1500s proved to be extremely influential in terms of how people viewed and understood deafness. This paved the way for the development and expansion of more modern and complex sign languages. In his book "Deaf Heritage," author Jack R. Gannon tells of how Dutch-born Rudolf Agricola in "De Inventione Dialectica," published in 1521, went against the conventional wisdom of the time to argue that if you were deaf, you could still learn language.

Around this same time, an Italian doctor named Girolamo Cardano began to teach his own deaf son by using symbols, proving — against common beliefs of the time — that those who were deaf were perfectly capable of using their minds and acquiring language (per the "Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies"). This led to Cardano publishing an influential book in 1575, which emphasized that for someone who was deaf, they could learn through reading and writing rather than through sound and voice.

By the end of the century, as explained in "A Place of Their Own: Creating the Deaf Community in America," a German doctor named Solomon Alberti wrote perhaps the first book ever dedicated solely to deafness, arguing that to hear and to speak were different things and that he witnessed firsthand deaf persons who could read words as well as read lips. Again, this shift toward understanding that those who were deaf were capable of language and being educated helped influence an evolving, more dedicated focus on developing new languages that could be signed.

A book on regional sign languages was published in 1644

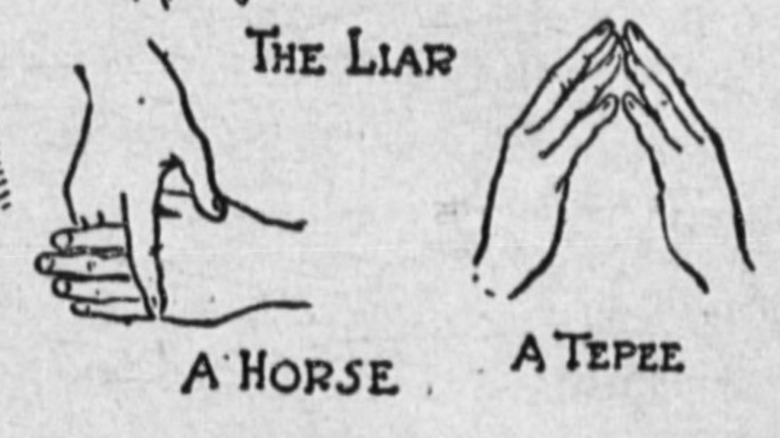

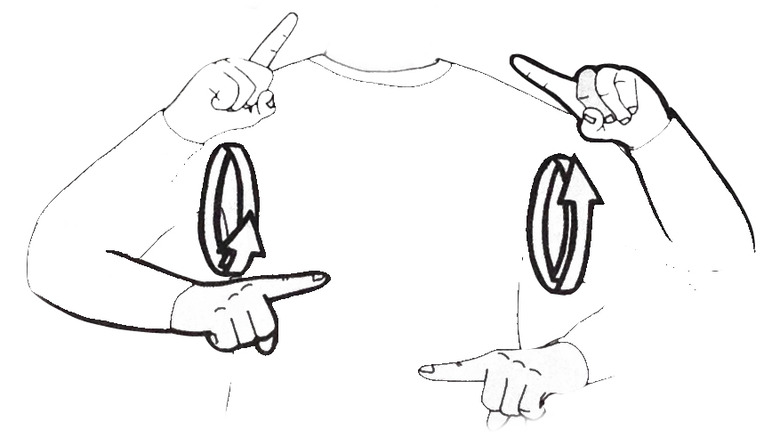

In 1644, a British doctor named John Bulwer published a book titled "Chirologia, or, The naturall language of the hand," which according to the American Psychological Association, demonstrated his belief that the hand "speaks all languages" despite any "formal differences" of one's spoken language. This was a landmark book for the development of more standardized sign languages. CSU Northridge explains how there were universal hand gestures, such as grabbing one's chest for expressing sadness, waving a finger to express disapproval, or using the middle finger to "chastise men."

Perhaps most importantly though, Bulwer discussed finger alphabet and number systems. CSU Northridge, which has an original print of Bulwer's book in its special archives, notes that at the time of its publication, such systems were already in use by those who were deaf, and Bulwer had argued that those who could hear would also benefit from learning nonverbal communication. One can see diagrams in "Chirologia" of these alphabet systems in Bulwer's original book and, while they're relatively simple signs, they bear resemblance to finger alphabets used today (via Yale University Library).

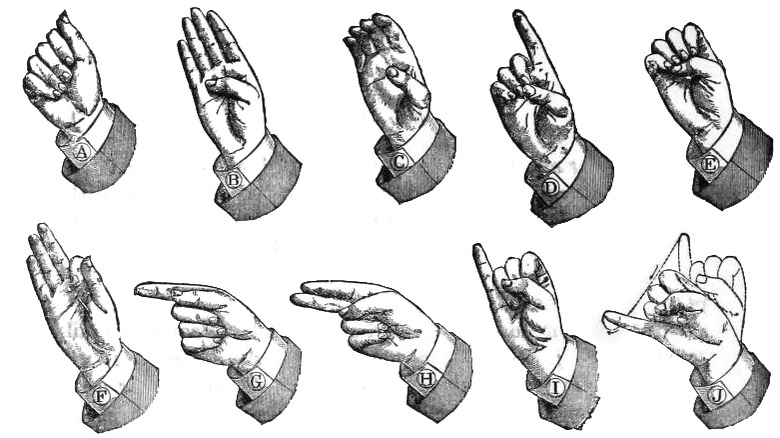

Monks influenced the use of fingerspelling

As previously described, before modern sign language existed, fingerspelling — also called the manual alphabet — was an influential communication tool for those who were deaf. In some instances, the growth of fingerspelling expanded due to European monks who developed and used it after swearing vows of silence. As described by BBC, some have even argued that these monks may have invented fingerspelling as early as the eighth century, although there are other competing theories as well. In a 2003 article for Sign Language Studies (via JSTOR), it is described how monks played a more vital role in its expansion during the 1500s, when they directly began to teach deaf children fingerspelling.

A 16th-century Spanish monk named Fray Melchor de Yebra became the first to publish the diagrams of the finger alphabet used by fellow monks, according to "A Place of Their Own: Creating the Deaf Community in America" by John V. Van Cleve and Barry A. Crouch. Melchor de Yebra's motive was that it could help those who were deaf learn the Catholic faith, but he further added that it could also help those on their deathbeds confess to priests even if they'd lost their ability to speak. While none of the friar's original writings survive, historians know of him and his charts due to a teacher of the deaf named Juan Pablo Bonet, who recreated Yebra's finger alphabet diagrams in 1620.

Servants in the Ottoman Empire helped expand sign language

As early as the 1500s, servants within the Ottoman Empire were hired specifically due to their deafness and their ability to communicate using only their hands. According to Koç University in modern-day Turkey, there was a significant number of those unable to hear living within Ottoman palaces as their hand languages were useful for political reasons as well as elite gatherings where secrecy was important.

The Independent Living Institute explains how these signs were complex and used by hearing people, too, including sultans, and were considered essential within the Ottoman court where the sultan would meet with private audiences, including many foreigners. According to a 2004 article in the Arab Studies Journal (via JSTOR), Europeans "marveled" at the ability of the sultan to converse with his deaf servants through sign language.

In a 17th-century history written by Sir Paul Rycaut, he described how they seemed to "perfect themselves in the language of the Mutes" and that there may have been as many as 100 working for the Ottoman court during this time. As described by JSTOR Daily, this use of signs was also cultural, as the relative seclusion practiced by the sultan also corresponded with silence and, behind the curtains, he could communicate silently with pages and officials, while those outside his quarters saw or heard his presence.

French sign language was an important development in the 1700s

During the mid-1700s, a Catholic priest from France named Charles-Michel de l'Épée, influenced by what is known as "Old French Sign Language," helped standardize a system of spelling and using simple signs to express ideas, a system that would eventually directly influence the creation of French and American Sign Languages, according to Britannica. He went on to create an educational institution in Paris for the deaf, which still exists as the National Institute of Young Deaf of Paris, and worked to develop a sign language dictionary, which was ultimately completed after his death (per the University of Pittsburgh).

There were many people who were against the teaching of sign language to the deaf for a variety of reasons. In 1779, Pierre Desloge, a 32-year-old deaf bookbinder living in Paris, France, published a book defending the use of and advocating for the use of sign language as the proper way to educate those who cannot hear, as noted in "The Deaf Experience: Classics in Language and Education" (via Gallaudet University Press). It is also possibly the first book published by a deaf author.

American Sign Language originated at the American School for the Deaf

In the early 1800s, American Sign Language, also known simply as ASL, was developed, having been largely inspired by the standardization of French Sign Language. According to Britannica, deaf students in the United States were able to receive a formal education with the creation of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817. The school was established by a minister named Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, who was inspired to do so while teaching his deaf neighbor named Alice Cogswell the alphabet (per Vassar).

As explained by the National Institute on Deafness, the formation of American Sign Language didn't come from a single person or group, but formed from various sign language families as well as French Sign Language. The institute notes that it's important to understand that American Sign Language is its own language, separate from English and has its own set of rules like any other language. By the 1830s, American Sign Language would be the primary signing language taught in the United States. In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill creating what was then called the National Deaf-Mute College, before eventually being renamed Gallaudet University after Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet — which today remains the only accredited university for students who are deaf in the entire world (per Gallaudet University).

There were debates over how much to emphasize sign language

Perhaps not surprisingly, there were many arguments over which approach educators of the deaf should take: the manual approach of emphasizing sign language or the oral approach using speech and lip-reading. This debate between manualism and oralism was significant and consequential. Oralists, who supported teaching lip-reading and speech, argued that using one's hands to sign was primitive and evolutionarily inferior to spoken language (per Gallaudet University). The shift toward oralism came in 1880 at the International Congress of Educators of the Deaf in Milan, which, as pointed out by British Deaf News, excluded deaf teachers themselves as delegates and used children who hadn't been deaf since birth as evidence that lip-reading and speaking were superior methods of teaching.

As noted by Yale University, teaching oralist methods isn't wrong per se, but it is less inclusive and works more for those who became deaf later in life. Despite this, teaching American Sign Language was actually outright banned in most schools for the Deaf in the United States by the turn of the century. During these decades, fewer and fewer teachers themselves were actually deaf, too. According to British Deaf News, whereas nearly half of all educators in deaf schools were themselves deaf in 1850, that number decreased dramatically with the focus shifting to oralism.

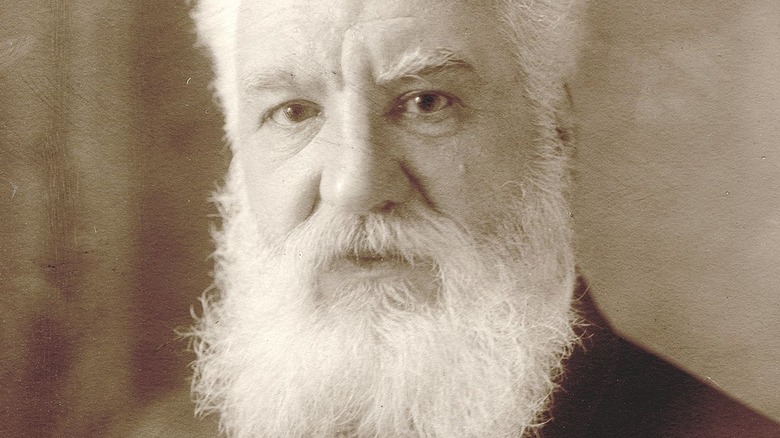

Alexander Graham Bell opposed American Sign Language

If one wants to point a finger at someone who may have been most responsible for the banning of American Sign Language in schools for the deaf, that finger could almost certainly be directed at influential inventor Alexander Graham Bell. As described by Yale University, Bell and Edward Miner Gallaudet (son of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet) had long and public disagreements over the emphasis of oralism with Bell, a staunch and vocal supporter. Bell, whose wife and mother were both deaf, argued that an oralist-only education would ensure those who were deaf would participate fully in society. In fact, his views went even more extreme, as he contended that deafness was a threat to American identity, believed deaf people shouldn't marry and potentially have deaf children, wanted to eliminate all use of sign language, and not permit deaf teachers in schools for the Deaf (per Gallaudet University).

In an 1894 speech, Bell claimed that oralists such as himself had "been ridiculed, their motives aspersed, their successes belittled, and their failures magnified," but that he was confident that his perspective was correct, despite opposition from manualists, who argued not everyone who was deaf could learn that method. As explained by CBC, Bell believed that those unable to hear were "defective" and this perception, which he helped mainstream during his lifetime, still helps maintain a negative cultural stigma towards those who are deaf.

The Dictionary of American Sign Language was a game-changer

In the 1960s, a linguistics professor at Gallaudet University named William Stokoe began studying American Sign Language as a legitimate language, rather than something inferior to a spoken language as was the common belief by many at the time. According to the National Science Foundation, when Stokoe applied for a grant to help fund his studies, he faced intense public criticism from the leading deaf educators of the time who had been embracing oralism for over half a century. Nonetheless, he persisted. The grant helped lead to the publication of the extremely influential "Dictionary of American Sign Language" which would assist in revamping deaf education in the United States and the return to teaching it in schools.

Eventually, this breakthrough would lead to the creation of "The Gallaudet Dictionary of American Sign Language," which is still widely used as a reference book today. This was overseen by Clayton Valli, a deaf linguistics professor at Gallaudet University, who further helped popularize the resurgence of American Sign Language with his poetry. As described by Gallaudet University, the book is an introductory text to American Sign Language that contains over 3,000 illustrations and a detailed English-language index.

There are many methods of teaching sign language today

Although the 1960s had helped transform Deaf education, even today, not everyone agrees on the best way to teach new learners sign language. Still, the goal of each teacher remains the same: fluency. According to Britannica, the oralist approach for so many decades had left 30% of deaf students in the United States illiterate and, for those who were literate, with an elementary-level reading level. While there remains disagreements and competing theories, nearly all have reintroduced sign language into their instruction. There has been a shift among experts toward viewing deafness less as a disability and more as a cultural difference.

The National Association of the Deaf explains how those who are deaf and hard of hearing have very different perspectives and life experiences, and while it officially endorses the use of American Sign Language, along with becoming bilingual in English, its mission statement states that it's inclusive of various opinions and beliefs. The association also makes clear that children who are deaf and hard of hearing can learn at the exact same levels as children who can hear when given equal access and opportunity.

Chinese Sign Language is the most widely used sign language

Education for the Deaf in China can be traced back to 1887, when a missionary named Annetta Thompson Mills established the Chefoo School for the Deaf in Yantai, China (via Smith College). By World War II, various sign languages began to spread throughout the nation. As a result, Chinese Sign Language has grown to have millions of users today, making it the most widely used sign language in the world. According to the journal Frontiers in Psychology, Chinese Sign Language, also called CSL, is actually made up of numerous variants, such as Shanghai Chinese Sign Language (SCSL), but government policy has recently pushed to standardize the variants into a single approved language. As described by China Global Television Network, the national standards were released in 2018 as the National List of Common Words for Universal Sign Language, and it includes approximately 5,000 words that are used commonly in China.

While this standardization is used by most educators in China, regional differences remain outside of classrooms (via "Sign Languages of the World: A Comparative Handbook"). Historically, these dialects were split between Northern Chinese Sign Language, which was influenced by American Sign Language, and Southern Chinese Sign Language, which was influenced by French Sign Language (per NYU Shanghai).

There are over 300 sign languages in use today

There are hundreds of different sign languages in use throughout the world today, used by over 70 million people, according to National Geographic. Traveling from one country to the next using sign language is no different than traveling to different countries using spoken language. While in spoken language, a word in one language can mean absolutely nothing or something entirely unique in another, in sign language different gestures can mean completely distinct words as well.

A few of these distinct sign languages include Martha's Vineyard Sign Language, used by residents of the island, predating American Sign Language (per The Atlantic). In the Negev desert of Israel, the Al-Sayyid Bedouin tribe created an entirely new and unique sign language over the past century to assist with its 4% of the population that is deaf (per New Scientist). Others include British Sign Language, Kata Kolok in Bali, Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana, Yucatec Maya Sign Language in Mexico, and Indo-Pakistani Sign Language in South Asia.

The United Nations, as made clear by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, treats sign languages as equal to spoken languages and says governments around the world are responsible for treating them as such. The United Nations General Assembly has even set September 23 as the International Day of Sign Languages.