Here's Why Dice Were Invented

What is luck? Can we rig the game of chance? When the fates speak through a rolling of the die, can we tempt to deliver a sweeter message? "Before the next session spend some quality time with your dice," writes user TwoButtonsOP on the subreddit r/DND. "Cook together, watch a movie or just simply go for a walk and look at clouds. These should help the dice relax and release the performance pressure they have to bring each time they are used." Another user in the thread had their dice blessed by a (Jewish) rabbi, a (Christian) bishop, and a (Muslim) imam. "These b******* still roll low, though. I'm out of ideas," they write.

"Teach a particularly bad die a lesson by 'punishing' it. This can be putting it in 'the shame bag' or even the freezer," an author writes on Nerdist. "If a bad die is clearly cursed ... it must be destroyed while the other dice bear witness."

These people have got to be joking, right? Not in the slightest. For the ancient Romans, the ancient Egyptians, and the early European American colonists, the stakes were much higher than a game of Dungeons & Dragons (although these stakes can be admittedly quite high).

Where did they come from and why are they still here?

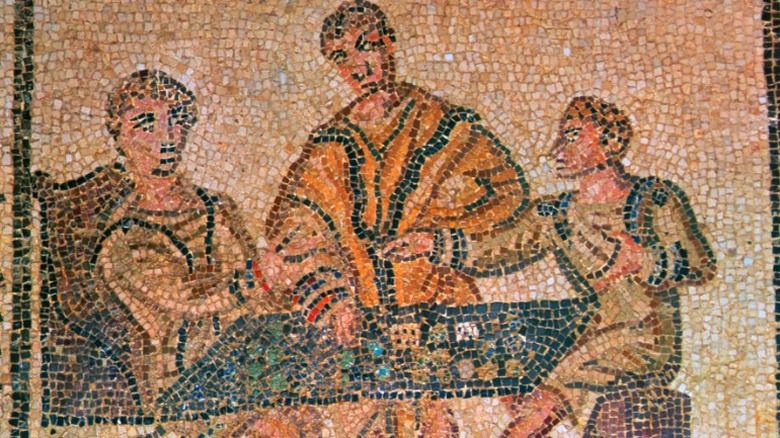

What was at stake? The favor of the gods. The outcome of a war. The deed to your home. A government contract. A marriage. An acquittal. The Romans, who used dice in augury and divination rites, believed luck was the favor of the gods — a perfect six was called a Venus, according to archaeologist Ellen Swift in "Roman Artifacts and Society," as seen in The Atlantic. But the Romans were just carrying on a game humanity had already been playing for thousands of years.

Six-sided dice were discovered in ancient Persia (Iran) and ancient Egypt long before the birth of Christ, then later found all over Europe and in the indigenous North Americas. While dice were certainly used for everything from gambling to divination, as Ian Stewart, author of "Do Dice Play God? The Mathematics of Uncertainty," notes in "Feeling Lucky? A Brief History of Gambling with Dice," they were also used for something for pretty much the same thing we use them for today: games of chance.

But where did these mysterious six-sided cubes originate? Why did we invent them? And why are they still here?

A game of chance & the Astragalus Divination Dice of prehistory

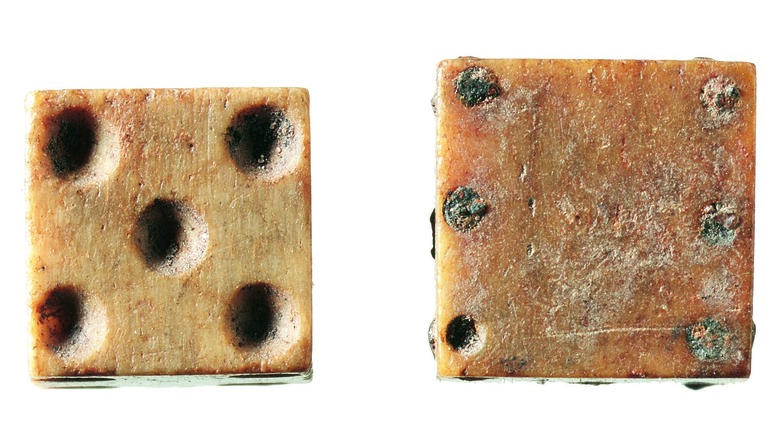

Dice were brought to Europe and the Netherlands by the ancient Romans — but the game didn't start there. Stewart says scholars believe dice may have originated in the Indus Valley as far back as 3200-1800 B.C. Dice didn't always look like they do today — before the 15th century, most cubes were asymmetrical — and they evolved from a game of fortune that didn't play with cubes at all, according to David S. Reese, author of the archaeology text "Worked Astralagi."

The very first dice probably originated from a prehistoric game of chance humans played with knucklebones. The ancient Greeks played it with the astragalus bone of a sheep, which lent its name to the astragalus die that later would replace these ornamented bones as a more standardized means of measuring fate, as Reese explains. The astragalus dice would survive to fly from knuckles and dictate fate through divination and cost peasants their fortunes in bad bets across pubs in ancient Rome, Lower Europe, and eventually the Netherlands.

The Aztecs and Greek Astragalomancy: the unpredictable with dice

The ancient Aztecs had their own games of chance that were sometimes used to correct inconsistencies in the calendar, according to H.S. Darlington (via JSTOR Daily's "The History of Dice"), who believes most early North American dice games originate from the Aztec games of chance.

Astragalus dice and similar implements have been found in Africa (where they were used in ritual divination, according to "Divination in South Africa"), the Near East, the Mediterranean, indigenous America, Lower Europe, the Netherlands — nearly everywhere there was culture, we seem to have divined a way of making sense of the unpredictable with dice.

"Dice potentially played an important role in conceptualizing divine action in the world," said Ellen Swift, author of "Roman Artifacts and Society" (via Happy Piranha). This is a framework that remains consistent. and as that concept of divine action changes, so do the dice and our use for them.

Chance, probability, and plague: Time to play fair in the pubs of Europe

Before 650 B.C. (according to Acta Archaeologica), dice could be virtually any shape and size, but later on they began to take on the standard six-sided form. Still, their configurations varied: the majority of dice didn't take on the number formation we recognize today near-universally until the mid-15th century, and at that point, everything changed.

Welcome to the early Renaissance (or the Late Middle Ages, if you prefer). It's the mid-14th century, and a lot is changing: but dice are all starting to look pretty much the same. Soon, nearly all dice were virtually identical to the ones in your junk drawer right now. The Renaissance had brought new ideas about rationality and objectivity to European trading hubs — and pubs. As rationality became a hallowed virtue, suddenly it did, in fact, matter how the die was cast and by whom: because you, the human being, believed you could influence it (unlike the Romans, who believed the fates dictated all).

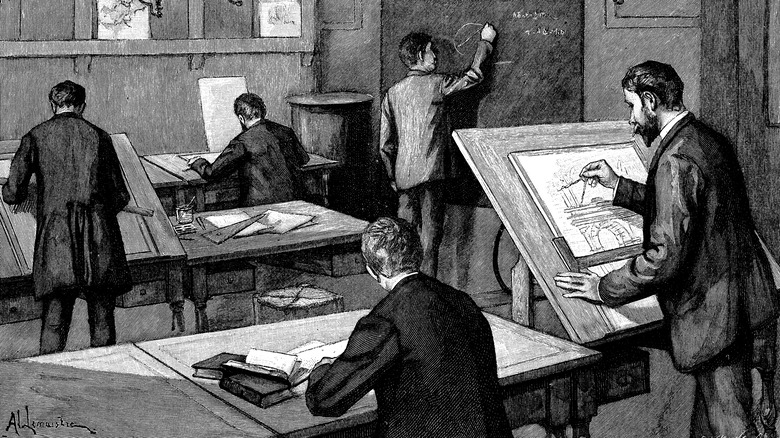

Enlightenment mathematicians want to get in on the game

"A new worldview was emerging — the Renaissance," explained anthropologist Jelmer Eerkens (author of a recent study on dice) in Medievalists. "We think users of dice also adopted new ideas about fairness, and chance or probability in games."

There was no more time for arbitrariness and asymmetrical dice in the life of a gambler or seance sage — this was the Renaissance, and objectivity mattered in a dice throw as in all other things. The joy of the game for early American colonists (whose dice games often involved stylistic skill) and of the randomness of the Romans' rites (decreed via dice that were so lopsidedly unfair that no post-Enlightenment player would dare cast their lots with a set) was in part the unpredictability — in the latter instance, it even transmogrified the divine into concrete outcomes we could act on as human beings. There will always be that unpredictability with any game of chance. However, with the (possibly mass-produced) symmetrical dice of the early modern period, that unpredictability became something we could predict: a concept we now know as probability.

According to Ian Stewart, author of "Do Dice Play God? The Mathematics of Uncertainty" (via "Feeling Lucky? A Brief History of Gambling with Dice"), it was those new standardized dice in the era of the Enlightenment that gave birth to an entirely new branch of mathematics.

Is the Renaissance about to invent a new math?

Mathematicians began studying the probability of outcomes and the mathematics of randomness in the mid-16th century, and they did so by studying games of chance (via New Scientist). They did so by playing dice. For purely educational purposes, of course. (This is false. These dudes loved gambling.)

In 1550, Italian mathematician and hardcore gambler Gerolamo Cardano published a manuscript on dice. Was this madman mixing business and pleasure in a deranged attempt to rationalize the tools of divinity and drunkards? Or was he onto something with this idea, and would a lot more mathematicians start getting into dice? According to M. Leung of the University of Texas at El Paso's Department of Mathematics, Cardano is today credited with the first Renaissance text on probability theory — what were the chances of that? When Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat brought the study mainstream about a century later — they, too, had been busy gambling, as Gizmodo reported.

We're still infatuated by the complexity of chance and the probability of the possible

But dice are toys! True. But they are also algorithmic hardware that can be used to calculate probability and chance, at least according to Stewart and his progenitors from the 16th century. All the better, Stewart says.

"'Toy models' are often misunderstood by everyone else, because they seem far removed from the complexities of the real world. But throughout history, major discoveries vital to the progress of science have emerged from toy models," explained Stewart (via "Feeling Lucky? A Brief History of Gambling with Dice). "The pioneers of probability theory had to extract sensible mathematical principles from the confused mass of intuitions, superstitions, and quick-and-dirty guesswork that had previously been the human race's methods for dealing with chance events." Fair enough. We invented dice to predict the unpredictable. Now, some would argue, we can predict even our own predictions about that.

A belated discovery and an end to all predictions — or not

If we've had dice for millennia, why did probability theory come so late? Before standardized dice (as described in "Dice Games") and before the Enlightenment, scientific thinkers (and religious ones, for different reasons) operated under the assumption that the universe was fundamentally deterministic. Dice were invented to ask questions of that determinism, and now dice are cast to decree quantifiable answers.

Even the ancient Persians must have dealt with the dilemma of chance. We know facts must be fixed in a logical world, but the reality is, facts seldom remain that way: Weather, wars, relationships, trade deals are all prone to leave us rolling short of our bets. We need a way to make sense of that — to engage with that chasm between the fixed and the possible. Dice were invented in reply as a prayer to disrupt the fixed — to disrupt that view of a finite world — and to discern something of the indiscernible, even if that thing is the decision we don't yet know how to make next. As long as the world remains full of indecipherable forces — and as long as we possess the desire to grasp them — dice will survive along with humanity, whether knucklebones or blackjack. We don't want to live in a world simply subject to chance, or worse, consigned to a fixed fate. Dice challenge that. We'll cast our bets.