Here's What It's Really Like To Go Undercover

Working undercover has an inherent glamour that's hard to resist. For one thing, it's incredibly risky — you're a law enforcement officer who gives up all the normal protections of your job in order to infiltrate a dangerous and illegal organization or subculture. You go in without a badge, without backup, and often without any way to easily communicate or call for help. And while undercover, you have to pretend to be someone you're not and live with the constant risk of being unmasked.

That's why stories about undercover investigations fascinate us. The longer and more dangerous the mission, the more thrilling the story becomes.

But there's another factor involved. Everyone likes to imagine themselves as a completely different person from time to time. What would have happened if we'd chosen a life of crime? What would it be like to leave all your connections behind and completely reinvent yourself? Undercover operations offer a chance to do just that with official blessing — you're given full permission and even encouraged to transform yourself. It's a tempting way to make a living, and when you add in the fact that you're doing good and helping to catch bad guys, it's even better.

The truth is a little more complicated than the movies or our imaginations suggest, however. Here's what it's really like to go undercover.

You can't break the law

One of the most popular tropes you find in stories about law enforcement officers going deep undercover is when they're forced to use drugs or otherwise break the law in order to prove themselves. It's all justified by the need to preserve their cover.

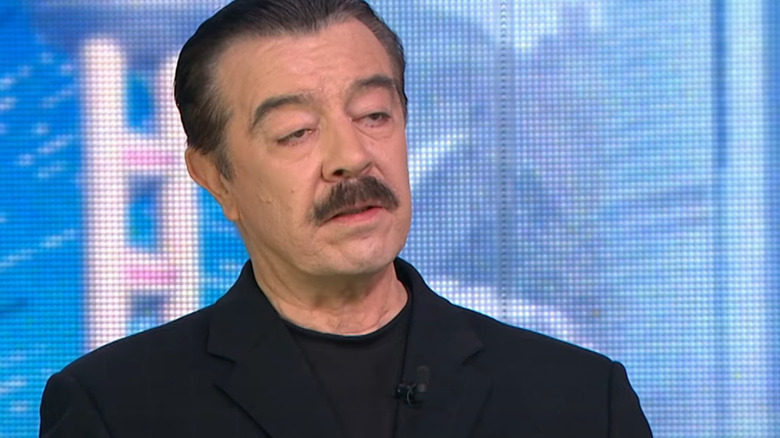

In reality, this doesn't really happen. As former DEA agent and The Cipher Brief contributor Mike Vigil told Insider, committing illegal acts would compromise the credibility of the agent (and thus the case they're building), making them useless as a witness in court, which is the whole point of going undercover in the first place. And former ATF agent Vincent Cefalu confirms this over at A&E True Crime, noting that part of his job as an undercover agent is to convince the criminals that he's worse than they are without actually committing any sort of heinous crimes. Cefalu does admit that sometimes minor crimes, like not paying for gas, would be unavoidable, but agents would come to the business the next day to pay the bill and explain what had happened.

Another point the agents make is that most criminals don't want to deal with drug addicts, so if you're working undercover in a drug-related operation no one expects — or wants — you to do drugs. And Vigil notes that if someone tried to force an agent to participate in illegal or violent activity, that agent would likely be pulled out of the investigation immediately.

There's a lot of paperwork

When we imagine working undercover, we tend to focus on the excitement of it — the thrill of being in constant danger, of fooling criminal masterminds and manipulating them into sealing their own fate. Certainly, films and TV shows depicting undercover work make it seem like it's a full-time job, an endless game of mental chess between the undercover operative and the criminals they're working to destroy.

But as reported by Insider, undercover work is still police work, and that means paperwork. Building a case and running an investigation requires a lot of desk work logging evidence and filing reports. Mistakes or missing data could compromise the whole operation, so this work needs to be done regularly. Even when you're risking your life pretending to be a criminal, those reports need to be filed.

According to BBC News, at the end of an undercover investigation, there's even more paperwork to be done in order to note all the broken laws the officer or agent observed. In fact, according to former FBI undercover agent Michael R. McGowan, when he was putting together a team to conduct undercover operations, one of the main things he took into account was the need for someone to keep up with the enormous amount of paperwork the investigation would require.

You're usually introduced by an informant

While undercover work might seem pretty straightforward — you pretend to be a criminal and get involved in crimes with people, take notes, and then arrest everyone — one of the most challenging aspects of the work comes right at the beginning: getting in.

While some undercover operations begin with a simple membership fee (undercover FBI agent Bob Hamer told Vice he began his investigation into one group by paying $35 to join up); most of the time, the agent working undercover needs a confidential informant, or CI, to make introductions. This is usually someone already involved in the criminal activity being investigated who has been arrested and offered a deal: that is, help the agent go undercover in exchange for reduced or dropped charges. Without a CI to make those introductions, an undercover agent would have to start at the very bottom of an organization or group and slowly make their way up, adding months or years to the time frame.

As noted by author Dennis G. Fitzgerald in his book "Informants and Undercover Investigations," confidential informants are also often immunized against any charges stemming from criminal activities they engage in that are observed by the undercover officer. This is called "charging around" specific criminal acts in order to avoid forcing the CI to testify in court, which could threaten their safety and make them useless as an informant in the future.

It can take years

One thing that TV shows and films get very right when it comes to undercover operations is the length of time they can last. While some undercover stings last just a few days, others can go on for years and totally take over an investigator's life.

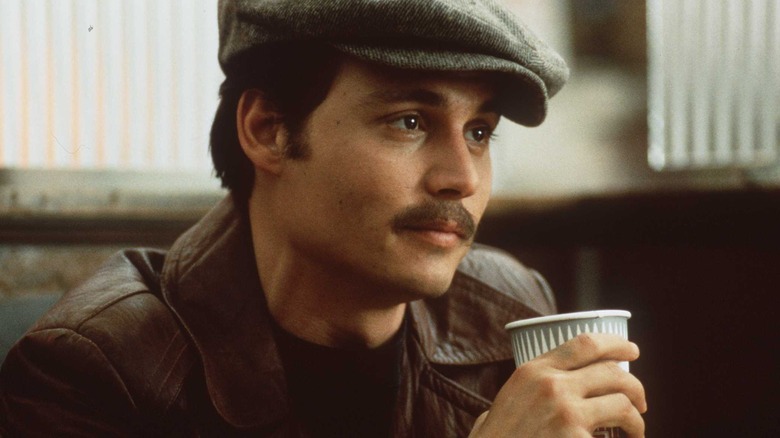

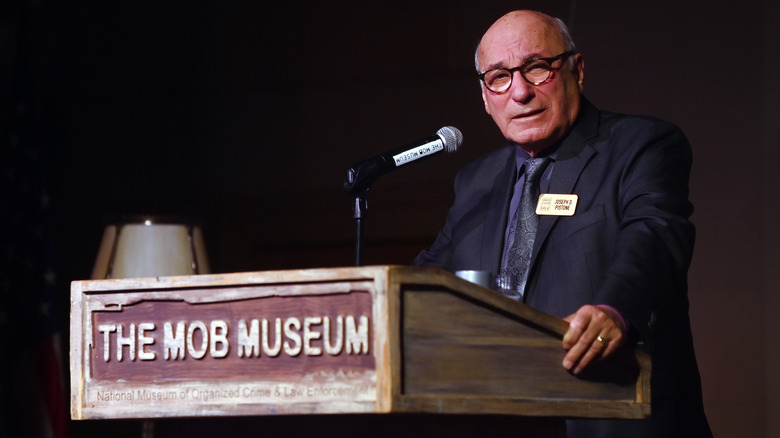

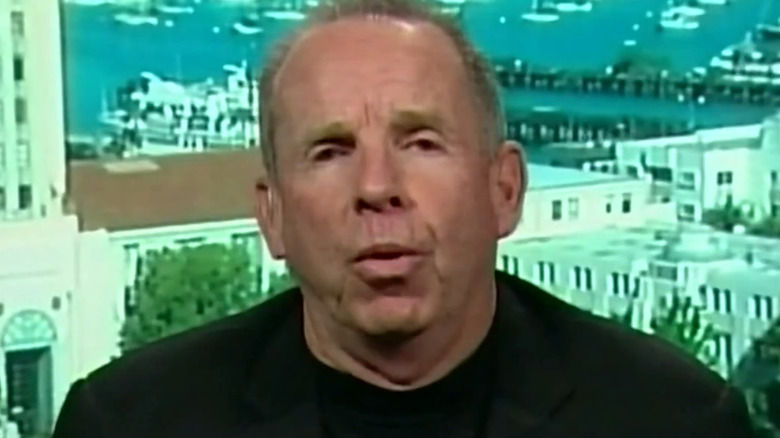

A classic example is Joe Pistone, the inspiration for the film "Donnie Brasco." According to the FBI, Pistone began an undercover infiltration of the Bonnano crime family in 1976. The operation didn't end until 1982 — meaning, Pistone spent six years pretending to be a small-time thief who wanted nothing more than to be a mafia associate. And according to Rolling Stone, FBI undercover legend Scott B. spent 18 months infiltrating the biker gang the Outlaws, one of dozens of long-term undercover investigations he's credited with. And according to Vice, another FBI undercover specialist, Bob Hamer, routinely spent years working undercover on cases, including a five-year stint investigating drug-dealing gangs in South Central Los Angeles.

According to Scott B., the time and effort involved in these kinds of complex undercover operations mean there's a very small number of law enforcement agents capable of doing them. He estimates that there are perhaps 50 agents in the country who have done five or more, and even fewer who make it into the double digits.

You have to identify with bad people

One of the worst aspects of undercover work is the need to identify with the people you're investigating — people who are, at best, criminals — and often far worse.

This isn't easy to do. Rolling Stone reports that FBI undercover agent Scott B. argues that in order to be convincing to the people you're investigating, you have to draw on some aspect of yourself — you can't rely on acting skills. "Acting will get you killed," he notes, suggesting that the trick is to be a "darker shade" of yourself in order to pass the smell test when persuading immoral criminals that you share their worldview. For example, Scott B. admits that if his life path hadn't taken him to college where he met other types of people, he might have been susceptible to neo-Nazi ideologies — and that small, dark part of his identity allowed him to seem plausible when infiltrating white supremacist groups.

This can be really stressful. As Hamer puts it, criminals can "smell fear" and they know if you're not really accepting of their lifestyle — often with disastrous results.

You work more than one case at a time

Despite the length and complexity of undercover investigations, which can often last years and require the agent to adopt what amounts to a complete second identity, many undercover agents have to work several cases at once. In part, this is because there are only a small number of law enforcement agents capable of doing the work. According to Rolling Stone, former FBI undercover agent Scott B. estimates just a few dozen agents in the country are capable of handling more than a few of these sorts of operations. Scott B. himself often had to work on several undercover investigations at once.

For another layer of difficulty, these undercover investigations often involve wildly different crimes and people. Another former FBI undercover agent, Bob Hamer, told Vice that while he was working undercover to stop an international smuggling ring in what was called Operation Smoking Dragon, he was simultaneously working to infiltrate and gather evidence on another criminal group. Incredibly, Hamer only had one cell phone while working these cases, meaning that when his phone rang, he never knew which of his two undercover personas he was supposed to be.

In fact, according to the Journal of Law and Policy, undercover police officers are often reluctant to testify in their own cases because they're still working undercover in other, often related, operations and worry about blowing their cover.

It gets increasingly dangerous

There's a tendency to view every undercover operation as a separate story, but the truth is, there are always several of these sorts of investigations going on at once. As a result, criminal organizations become increasingly aware that they're being targeted and increasingly familiar with the techniques undercover investigators use to fool them.

According to The Guardian, that means the danger to individual undercover agents grows steadily the longer they work. While the initial introductions can be nerve-wracking, it's often not until the undercover agent's work begins to spur arrests that things get really dangerous, because the criminals start to wonder who's feeding the police information. Neil Woods, a former undercover drug agent, saw firsthand how the gangs he was buying drugs from became increasingly suspicious of any new faces — and unleashed violence in order to terrify informants as a result.

And that's in addition to the increasing dangers that come simply from associating with criminals and being in criminal-dominated neighborhoods and areas. As reported by the Virginian Pilot, undercover police officers are often robbed, assaulted, and even killed — often by criminals who have nothing to do with the case they're working. The more time spent undercover, the higher the odds a law enforcement officer will experience violence like that, no matter how careful they are.

It can get really confusing

As noted by The New York Times, the use of undercover agents at all levels of law enforcement has been increasing for years. It's an effective tactic, after all. But with 40 federal agencies known to employ undercover agents and most local police forces engaging in the practice as well, it's no surprise that things can get a little confusing. Working as an undercover investigator often means you're not entirely sure that the criminals around you aren't also undercover officers.

This has real consequences. Newsweek reports that two separate police precincts in Detroit, Michigan, got into a flat-out brawl when officers from the 11th precinct tried to arrest undercover officers from the 12th precinct posing as drug dealers. According to Fox 2 Detroit, the precincts had not communicated their plans to each other, and when more police from the 12th precinct arrived, the confrontation descended into a full-on brawl, with guns drawn. At least one officer had to be taken to the hospital to treat injuries suffered during the fight.

The confusion ended up embarrassing for the police, but it could've been much worse. The level of secrecy required in many undercover operations means this sort of confusion could easily lead to undercover agents being injured — or even killed. And in Great Britain, an undercover agent named Mark Kennedy was accidentally arrested while infiltrating a group of environmental activists, causing the whole case to collapse, per The Guardian.

You can get lost in the role, and even get married

Working undercover is all about adopting a persona and living that persona so thoroughly that other people — even naturally suspicious folks like professional criminals — believe you're someone you're not. Unfortunately, this can lead to what you might call collateral damage. In fact, it's not unheard of for some undercover agents to get so lost in their role that they get romantically and physically involved with — and sometimes actually marry — people caught up in their investigation.

BBC News reports that in Great Britain, the Metropolitan Police was sued by a woman who engaged in a long-term romantic relationship with a man she believed was a fellow activist — but was, in reality, an undercover police officer. Another British woman was engaged to a man she later discovered to be a police officer working undercover, according to The Guardian — and she actually lived with him for two years and never guessed he was lying to her. Even worse, the officer was already married and had children.

Sometimes, undercover agents have more than one intimate affair. As reported by The Guardian, undercover officer Mark Kennedy spent seven years infiltrating an environmentalist group. During that time he had numerous relationships with women he was lying to and reporting on, leaving at least one feeling "violated."

You handle your own outfit, and sometimes it shows

Since law enforcement agencies conduct so many undercover operations, you might imagine they have a pretty sophisticated setup that includes costumes and disguises provided to the agents. You would be wrong. As reported by Slate, according to Bob Cooke, a retired special agent with the California Department of Justice, when he was selected to begin working undercover, the first thing he had to do was go out and buy an appropriate wardrobe. Cooke notes that law enforcement has a culture, and part of that culture is a way of dressing, so he didn't have anything in his closet that would work.

This can be problematic when undercover agents aren't clued into how the people they're infiltrating dress. As noted by GQ, when protests erupted around the country in the summer of 2020, many undercover police officers infiltrated the marches — and were embarrassingly obvious because they weren't dressed naturally. In fact, the officers all followed the same pattern: steel-tipped boots, jeans, fleece jackets, and baseball caps worn backward. This made them very easy to spot in the crowds and undoubtedly compromised their ability to achieve the goals of their investigations.

One reason those cops failed to fit in? Just like Cooke, they had to supply their own clothes for the assignment. Since they weren't actually activists, their wardrobes simply didn't match up.

You'll usually have a cover team

Working undercover seems like a lonely and extremely dangerous job — and it certainly can be. But something that's sometimes overlooked in the movies and on TV is the fact that most undercover agents have what's known as a "cover team" backing them up, even on long-term missions. A cover team, as explained by Robert Knuckle in his book "A Master of Deception," is one or more other officers who act as a backup and who monitor the situations the undercover agent gets into. Their role is to offer support and to ensure the undercover officer's safety.

That's comforting, but it's not a perfect system. As retired special agent with the California Department of Justice Bob Cooke told Slate, one big weakness of the system is the lack of easy communication between the agent and their cover team. When Cooke was working one of his earliest cases, his cover team consisted of just one other officer — and they lost contact with him almost immediately. Cooke was completely unaware that he was operating without any backup at all and completed the drug transaction he'd come to do. But the dealer he was targeting thought he recognized him — he even knew the name of Cooke's wife — so Cooke was in tremendous danger at a moment when his cover team was completely out of the loop.

The PTSD is real

While undercover investigations seem exciting, they exact a real price. Many former undercover agents report suffering from various mental health challenges, ranging from difficulty fitting back into their old lives to full-on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

As noted by former undercover police officer Bob Delaney, it's often about betraying people who became your friends. He notes that the trust and bonds of friendship he formed while working undercover were very real — and it felt like betrayal when he filed his reports and got his friends arrested. On the other hand, The Herald reports that undercover officers often experience extreme feelings of isolation. They are away from their friends and families for long periods of time and often wind up pushing their loved ones away when they return.

As noted by USA Today, contributing to the problem is a lack of mental health support for undercover operatives. Many undercover agents resort to alcohol or other coping mechanisms that only make their problems worse because there's no easy access to private mental health support, and their support system either doesn't understand what they're going through or are also undercover agents with the same blind spots. The result is men like Mark Kennedy, who, The Guardian reports, emerged from a lengthy undercover operation confused and depressed, stating that he had "shattered" the trust he once had with friends and family and that "it's going to be a long process to find out who I am."