The Untold Truth Of Anita Hill

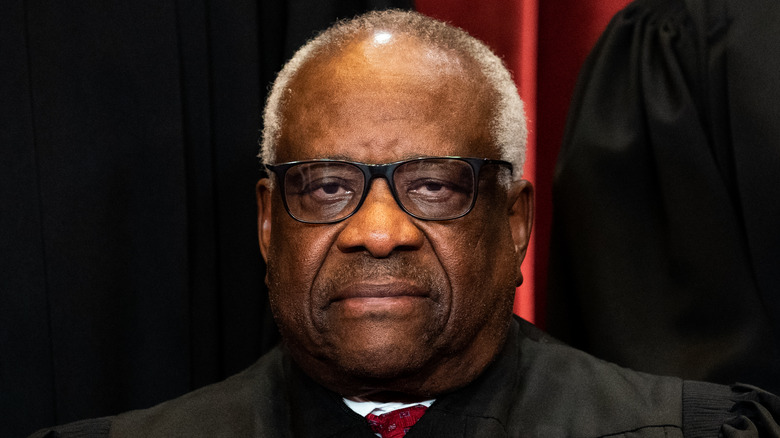

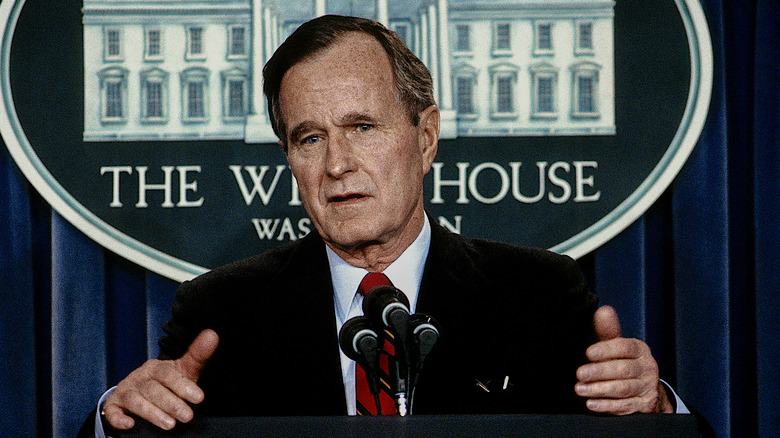

Before the Brett Kavanaugh hearing, and before Mitch McConnell's refusal to grant Merrick Garland any consideration, the testimony against Clarence Thomas made him the most contentious nominee for the Supreme Court in modern history. He didn't start out with that baggage. When President George H. W. Bush first proposed him in 1991, his resume was thin, according to Jeffrey Toobin's "The Nine." And the Judiciary Committee was evenly split in their vote on him, but there was no significant opposition to his confirmation in the full Senate. That all changed on October 6, when the press began reporting on the claims of one Anita Hill.

Born and raised on a farm in Lone Tree, Oklahoma, according to Britannica, Hill studied psychology at her home state university before going to Yale for a law degree. She held positions in the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in the early 1980s and went on to a teaching career back in Oklahoma. But it was Hill's televised account of the sexual harassment she said Thomas subjected her to while they worked together in government that elevated her to national attention.

Hill's testimony did not prevent Thomas' confirmation; he was confirmed in a 52-48 vote. But her willingness to publicly share an account of sexual harassment — and the aggressive behavior of the senators questioning her — left a lasting impact on conversations about harassment and the role played by women in politics.

Her family spanned the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement

In 2011, Anita Hill published "Reimagining Equality: Stories of Gender, Race, and Finding Home" on the housing crisis and the impact of gender and racial prejudice on communities. She opened it with an account of her own family, and in an interview with Brandeis Magazine to promote the book, she discussed a few surprises found while doing her research. Hill — who was born in 1956 (via Encyclopedia.com) — grew up with stories that her grandfather had been a slave, a claim that she found hard to square with the Civil War's ending in 1865. In digging through old census records, she found her answer.

Hill's grandfather, Henry Eliot, was born in 1864, in Arkansas, to a mother, Molly Eliot, who had been sold away from her husband. Emancipation effectively reached Arkansas in June 1865 (per the Arkansas Times), so Henry's time in bondage was admittedly brief. After freedom, Henry grew up and had children. But he wouldn't father Hill's mother, Erma, until he was in his 40s, and she in turn wouldn't give birth to Hill until her 40s. Their having children relatively late in life is what accounted for the family seeing both the end of slavery and the civil rights movement of the 1960s in just two generations.

She worked for Clarence Thomas twice

After graduating from Yale, Anita Hill began her law career in private practice. According to Politico, she soon found herself wanting work that was more personally fulfilling and valuable to society. In 1981, she accepted a position as attorney advisor to the assistant secretary for civil rights at the Department of Education — Clarence Thomas, at that time. Within three months, Hill said that Thomas began behaving inappropriately toward her around the office. He pressured her for dates and, when she refused, began discussing his sexual habits and abilities with her despite her telling him that the subject made her uncomfortable. "It was almost as though he wanted me at a disadvantage," Hill said, and she suspected that leaving her vulnerable was of greater interest to Thomas than sex.

The inappropriate remarks ceased for a time, according to Hill. In 1982, he moved to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and asked Hill to join him. With President Ronald Regan openly willing to shut down the Department of Education and Hill wanting to continue working in civil rights, and with Thomas' behavior having improved, she accepted. But shortly after the move, she said the harassment resumed, culminating in some innapropriate jokes. Hill developed stomach pain (stress-related, she suspected) that sent her to the hospital and began to fear for her job. She left on her own terms by 1983.

Her initial accusations were private

After leaving Clarence Thomas' employ, Anita Hill found work as a teacher at Oral Roberts University in Oklahoma. Despite her long discomfort with her former boss' behavior, according to Politico, Hill remained in phone contact with Thomas as a conduit for messages. When people around her spoke admiringly about Thomas, she would offer vaguely agreeable replies. "I could not afford to antagonize a person in such a high position," she later explained. Hill did not volunteer any of her experiences with Thomas, not even when he was nominated to the Supreme Court in 1991. She never intended to go public with her accusations or to directly challenge Thomas over them (per The Root).

What she did do was provide a statement to the FBI. According to NPR, Hill was conflicted about whether to do even that for fear of being publicly identified, but as Thomas' televised confirmation hearings focused on his legal views, senators became aware behind the scenes of rumors concerning Thomas' sexual harassment of female staff. After the hearings concluded, then-Senator Joe Biden, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, requested additional investigation by the FBI, leading to an interview with Hill and an affidavit by her sent to the committee. Hill's name, and any suggestion that Thomas' character was in question, did not become public knowledge until Hill's name and story were leaked to the press ahead of the final confirmation vote on Thomas' nomination.

She wasn't the only one with complaints against Clarence Thomas

After providing the Senate Judiciary Committee with an affidavit and the FBI with an interview, Anita Hill was called to testify before the committee over her allegations against Clarence Thomas. According to Politico, the all-male panel subjected her to intense scrutiny, picking over gaps between her testimony and her statements to the FBI. Republicans on the committee accused her of perjury and fabrication, and even some of the questioning from Democrats suggested Hill may have had ulterior motives (per NPR).

Hill was not the only woman with complaints about Thomas, however. According to PBS, his former director of public affairs, Angela Wright, was prepared to testify to the committee that she had also suffered sexual harassment while serving under Thomas. And Sukari Hardnett, who like Hill worked as special assistant to Thomas in the 1980s, was also willing to come before the committee. In a 2018 interview with NPR, Hardnett said that she herself was not subjected to harassment, but she and other young Black women would be "auditioned" for whatever needs Thomas might have and were expected to be at his beck and call whenever needed.

Despite their willingness to come forward, neither woman was invited to testify before the committee. The concurrent FBI investigation likewise passed over interviewing potentially corroborating witnesses for Hill, seeming to value brevity over thoroughness, according to the Washington Post.

She faced bomb threats

Anita Hill's concerns about being publicly identified in connection to the Clarence Thomas hearings proved to be well-justified. Besides the aspersions thrown against her by members of the judiciary committee — Sen. Orrin Hatch implied that part of her testimony came from "The Exorcist" (per NPR) — she faced considerable repercussions away from Washington. Speaking to NPR in 2021, Hill recounted various threats and humiliations she was subjected to after her testimony. Insults and death threats came through the mail. In one case, possible human feces was sent to her. She also endured threatening phone calls.

One of the most vivid — and alarming — incidents came on a Friday. Hill was in her home, with her 80-year-old mother, her sister, and her sister's three children all gathered for a family visit. That evening, she received a call from the dean of the College of Law at the University of Oklahoma. There had been a bomb threat made against Hill's home, and she and the dean needed to make the call on whether the threat was serious enough to warrant an evacuation.

Hill did not share the answer to that dilemma in her interview. But she did volunteer a concern that, in the age of social media, such threats against public witnesses have become even more pervasive. "We have not stopped that," she said, "and the uncertainty that's created by the systems we have in place really helps fuel that."

She was pressured out of a teaching job

After leaving her legal work for the government (and Clarence Thomas), Anita Hill turned to teaching. She took a position at Oral Roberts University in Tulsa (per Biography) and later moved to her alma mater, the University of Oklahoma, in 1986 (per AP). Hill had studied psychology while attending OU as a student (and graduated with honors), but as a member of the College of Law, she taught commercial and contract law. She made school history in 1989, when she became OU's first tenured Black professor.

Unfortunately, the fallout from Hill's testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee followed her back to her job. She resumed her teaching duties after the 1991 hearings, despite repeated requests for interviews. She did accept a limited number of speaking engagements on the subject of sexual harassment and spent the 1994-1995 school year on leave to author two books. But her presence on the faculty of a prominent university in a red state invited considerable pressure from conservatives.

It came to a head in 1996, when Hill offered her resignation. In her letter, she said that OU was "a fine academic institution with potential to be a great academic institution." She also wrote that her decision came from weighing her hopes to keep teaching at a premiere college in her home state against "my desire to work in an academic setting whose support of diversity of ideas and perspectives and appreciation of academic freedom is uncompromising."

Clarence Thomas fired back in his autobiography

To say Clarence Thomas didn't take kindly to Anita Hill's testimony is putting it mildly – very mildly. In his own testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, he strongly denied all of her claims against him. He also insinuated that Senate staffers went out of their way to dig up things on him. "This is a circus," he said, according to a transcript from the University of Virginia. He also framed the accusations as a racial attack, calling the hearing "a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves."

Several women who worked for or knew Thomas spoke in his defense (per The Washington Post), and he was ultimately confirmed to the Supreme Court, though the 52-48 vote was the closest in almost 100 years (per History). But receiving support and getting the job doesn't seem to have inspired any magnanimity in Thomas. In 2007, he put out his autobiography, "My Grandfather's Son." Considerable pages were devoted to the accusations, the hearing, and Hill personally. Thomas called her "my most traitorous adversary." He claimed her work for the EEOC was poor, that she only got work in the Reagan administration thanks to him, and that she was allied with left-wing forces determined to keep him off the Supreme Court. For her part, Hill vociferously pushed back against Thomas' characterization in a New York Times op-ed.

Ginni Thomas wanted Anita Hill to apologize

Absent from much of the contemporary commentary around Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas was mention of his wife, Virginia Thomas, known as Ginni. They met in 1986 and married the following year (per USA Today), after Hill worked for Clarence and experienced his alleged harassment. Like her husband, Ginni is an outspoken political conservative. She was the founder of the short-lived Liberty Central lobbying group and served as an executive for the Heritage Foundation. Her activism has raised eyebrows over the years. As of July 2022, it has most recently made her a person of controversy for her communications with members of the Trump White House leading up to the January 6 Capitol insurrection.

In 2010, however, Ginni was in the news for a less violent source of controversy. According to the New York Times, she called Hill — whom she had never met or spoken to — with an unusual request. "I would love for you to consider an apology sometime and some full explanation of why you did what you did with my husband," she said in a voicemail. Hill was unsure if the message was genuine at first. Ginni confirmed through a statement that hers was the voice on the message, which she characterized as an "olive branch." "I appreciate that no offense was intended," Hill replied through the press, "but she can't ask for an apology without suggesting that I did something wrong, and that is offensive."

She got an (unsatisfying) apology from Joe Biden

When Anita Hill testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991, its chairman was then-Sen. Joe Biden. Some of his statements and decisions regarding Hill's accusations and testimony were viewed as unusual (per NPR). Ahead of the committee's vote to advance Clarence Thomas' nomination to the Supreme Court, when rumors of misconduct had begun to circulate away from public scrutiny, Biden issued a statement. "I believe there are certain things that are not at issue at all. ... and that is [Thomas'] character," he said. "I know my colleagues, and I urge everyone else to refrain from personalizing this battle." During Hill's testimony, Biden interrupted her, pressed her for details on embarrassing and traumatizing stories, and allowed insinuations against her by his Republican colleagues (per Politico).

Decades later, before announcing his candidacy to become the 2020 Democratic nominee for president, Biden paid Hill a call. By her account in a 2021 NPR interview, Biden apologized for Hill's experience at the Capitol in 1991 and detailed his subsequent advocacy for, among other things, the Violence Against Women Act and a campaign to reduce violence on college campuses. Hill expressed gratitude for Biden's work on behalf of women. On the other hand, Hill took issue with Biden's apparent failure to understand the impact his role in the Thomas hearings had on other people beyond herself, or that the process of coming forward with information like hers about a nominee was flawed.

She helped bring on the Year of the Woman

Anita Hill's testimony did not prevent Clarence Thomas from being confirmed to the Supreme Court, and she initially found her life after the hearings isolated. But while promoting her book, "Believing," on NPR, she said that her testimony inspired women to reach out with stories of their own experiences with sexual harassment. And it wasn't only in private messages either. "Thirty years later," Hill told NPR, "I'm here to say that even though Clarence Thomas was confirmed, I do believe that what I did was effective because it opened the conversation publicly in a way that had never been done before."

Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton concurs. "Sexual harassment was something women didn't even want to speak about," she told a Georgetown Law Center event (via the Washington Post). "It is very hard to think of any legal proceedings that had the effect of the Anita Hill hearings." Besides Hill's own words, her treatment at the hands of the all-male judiciary committee upset many voters, particularly women. 1992 set records for the number of women campaigning for public office, according to ABC News, and that November, four women became senators and 19 became representatives in the "Year of the Woman." That may not seem like many, but prior to 1992, there were only two women senators and 30 representatives. As of 2022, those numbers have risen to 24 and 123, respectively, according to CAWP.

The testimony helped pass an anti-harassment bill

If Anita Hill's testimony couldn't keep Clarence Thomas from the Supreme Court, it did indirectly help advance legislation to help victims of sexual harassment. The Civil Rights Act of 1991 was held up in Congress after two years of debate, largely thanks to the stated opposition by President George H. W. Bush, according to Up Counsel. He had already vetoed a 1990 effort to amend the CRA over concerns about potential racial hiring practices. The move proved unpopular, and a wave of sexual harassment cases argued in favor of an amedment that could push back on discrimination.

In the face of public pressure, Bush submitted his own plans for a civil rights bill to Congress. Neither civil rights activists nor the president's own party were happy with his compromise proposal. Bush publicly vowed to veto the 1991 bill as well, dismissing it as a "quota bill," according to TIME. But the public fallout from the Hill hearings changed his mind.

The CRA of 1991 allowed for a trial by jury as an option in discrimination cases and enabled harassment victims to seek federal damages awards as compensation. The cap for damages was set at $300,000. The act has also been credited with improving education on matters of discrimination and harassment in the workplace as well.